One of the significant issues that were ignored during the Bihar election discourse is how the state has remained a catchment area for labourers and how they have been historically exploited to make profits from their labour. Even today, they are unwittingly caught in the labour contracting system—the missing piece of conversation in the Bihar model of development. There exists a social texture to the hidden nature of class, i.e., the social relations of exploitation of Bihari migrants via the labour contracting system.

Though a few political parties spoke of providing employment and ensuring freedom from unemployment (berozgaari se azadi), they did not touch, let alone address, the working conditions of Bihari migrants across India. While a number of Bihari youth aspire for a government job (sarkari naukri), getting one is not easy because of numerous reasons such as competition, eligibility and so on. However, a disproportionate number of Bihari migrant labourers, who may also aspire for a naukri to achieve stability, continue to work by doing kaam—for instance, in textile factories or construction work with little social and financial security. This freedom from unemployment has been one of the key conversations in the state of Bihar obscuring exploitation of labourers at workplaces.

Another significant form in which conversations on Bihari migrant labour have been visible to the public is through events of their exodus in large numbers from cities like Nashik, Mumbai and Delhi as a result of anti-migrant sentiments and acts of physical violence against Biharis. The stigmatisation and stereotyping of Bihari labourers have shaped how they continually serve as a convenient scapegoat for all crimes committed in towns and cities where they work across India. However, at the same time, there has been a clear valorisation of Bihari migrants’ capacity to labour that has made them move outside the nation in search of work in general—for instance, the recent recruitment for Israel for construction work in particular. It is at the nexus of the contradictory processes of stigmatisation and valorisation of Bihari labourers that we need to locate their exploitation, moving the lever of attention away from the dominant focus on the causes of migrant journeys.

Labour migration from Bihar—which started in the 1990s—is not a new phenomenon. It goes back to the British colonial era. However, the trajectories of migration have evolved and shifted—for instance, from labour migrating to tea gardens in Assam to working in Indian and the Gulf construction industry.

Such patterns of migration also signal the role of the state (in Bihar) and its alliance with the capitalists in controlling the mobility of labourers. For instance, when the COVID-19 pandemic swept across the world, the country went into a complete lockdown on March 23, 2020, impacting millions of migrant labourers in India. Migrant labourers could be seen walking thousands of kilometres on foot to get back to their villages. Worse, the mobility of migrant labourers working in construction sites in states such as Karnataka was restricted by building companies so that the labourers continued to work. This is the point where the Bihari labourers pleaded with the government of Bihar to make arrangements to bring them back to Bihar. However, there were little to no active attempts by the government to facilitate their return.

Since Bihari migrant labourers often oscillate between their places of work—cities in India—and their home villages, their movement often invisibilises their exploitation. More importantly, the form in which exploitation happens has changed, which remains hidden as to how the poor, out of compulsion, continue to be exploited. In the context of the migrant-intensive building construction industry, the architecture of exploitation centrally hinges on and has continually been sustained through the labour contracting system, colloquially known as the thekedari system, in shaping the accumulation of profits. Not just in India, contracting is present in the countries of the Global North, such as in Italian agriculture, where Punjabi migrants work under the caporalato contracting system. A similar variant in the construction industry exists in the Gulf countries, which is known as kafala (though this is being restructured, if not abolished). However, we know very little about how labour contracting—in the context of internal labour migration for construction work in India—is organised in shaping exploitation.

The building construction industry mobilises migrant labourers from Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal and Jharkhand through thekedars who act as intermediaries. The system comprises a relationship between thekedars and builders who run the construction projects, with no contract between labourers and builders. At a construction site, one can come across between 10 and 150-200 thekedars. Profits are extracted through the nexus of thekedars and the real estate companies. Thekedars from Bihar, who are mostly from upper caste Hindus and Muslims (but also Dalits), interlock labourers across different castes and religious backgrounds by recruiting them for building construction work. Some labourers may own land back in their villages, while others may not, indicating the differences among Bihari labourers as well. This recruitment is facilitated by paying cash in advance varying from Rs 2,000 to Rs 100,000 to find potential labourers. This cash is largely used by the women in the households for spending on everyday expenses or in some cases, on agricultural work. However, some thekedars also facilitate payment in kind—such as foodgrains—to the families of labourers. In return, labourers work at construction sites to repay the debt they owe to their thekedar. Such a debt-based labour recruitment has historically remained the norm under the thekedari system in different disguises, although not limited to Bihar. For instance, there is the dadan-based contract for Bengali migrants, who work for 61 days for a given sum of money. In addition, labourers are accommodated in rent-free makeshift spaces in or near construction sites designated as labour colonies or camps—with around 10-15 labourers working for the same thekedar accommodated in the same room—organised by builders who may also make arrangements for food through community kitchens run by the thekedars. However, most Bihari labourers prefer to cook food inside their rooms and do not eat in community kitchens. For labourers’ daily subsistence at the sites, thekedars could be paying a sum varying between Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 per week to each labourer, also called khuraki. The system of cash in advance, complemented by paying khuraki, serves as the foundation of the exploitative architecture of labour contracting.

Mobilising Bihari migrants, among others, as construction labourers enables thekedars subcontracted by builders to undertake different stages of construction work in cities. Labourers’ wages are accounted for by the difference between what labourers owe to their thekedars (having accepted advance) and what thekedars owe to their labourers (having paid them khuraki). Through the system of paying cash in advance and further paying weekly subsistence to labourers, thekedars siphon a share of the surplus equivalent to the difference between the contractual wages paid by builders to thekedars for their labourers and the subsequent wages paid by the thekedar to their labourers (as the difference between advance and khuraki) which is roughly Rs 150-Rs 250 per labourer per day. For instance, if a thekedar has a network of 100 labourers working at the same or across different construction sites in one or more cities, then it is likely that a thekedar has the potential to accumulate a surplus of Rs 15,000-Rs 25,000 per day. However, thekedars can even operate with as few as 10 labourers, which generates a surplus of Rs 1,500-Rs 2,500 per day. In so doing, while thekedars are keen to form their labour contracting network, they are also keen to expand and reproduce the same to be able to continually access contracts from builders.

While the architecture of exploitation in the construction industry is orchestrated by the thekedari system embedded in caste, gender, region and religion, it is further enabled by the role of the state through its absence in enforcing the labour laws that govern the contractual relations between the thekedars and the builders, and also through its presence visible in the builders’ compliance with how they record wages offered to thekedars on behalf of their labourers and how the thekedars comply with the Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970, and the Inter-State Migrant Workmen Act, 1979, for accessing a licence to recruit migrants as a labour contractor.

The recent selective exclusion of Muslim migrants to vote in the Bihar elections is an attempt to obscure the real issues of exploitation of migrant labour alongside identifying ‘selective worthiness of migrants’ to participate in the democratic process, whilst continually denying migrant labourers the “right to have rights”, reinforcing their internal alienness as citizens of the nation. This exclusion from claim-making on the state needs to be seen as a process of differentiation, in this case on the grounds of religion, in enhancing the possibility for the exploitation and oppression of the bad migrants—Muslim migrant labourers—much more than non-Muslim Bihari labourers, sustaining the wider project of global capital accumulation. This clearly indicates the contradictory role of the state, which on the one hand valorises the labour power of Bihari labourers, while on the other, selectively differentiates to reinforce the possibility of further exploitation.

While migrant workers’ ability to vote is significant and is largely a function of state power, going beyond workers’ ability to vote enables us to situate the class power of migrant labourers in addressing exploitation via the thekedari system and to (re) imagine the role of the state in facilitating the same. This is why the Bihar model of development, be it Badlo Sarkar, Badlo Bihar (change the government, change Bihar), or the slogans of Berozgaari se Azadi (freedom from unemployment) needs to engage with the question of the historical and intergenerational exploitation of Bihari migrant labourers. While the Bihar model of development is visibly concerned with improvements in access to quality health services, education, public safety and women empowerment, it cannot overlook the need to address the experience of migrant labourers who do mehnat (labour) for 14-16 hours a day far away from their villages.

Though the regime of the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) changed the lives of Muslims in Bihar, particularly to live with dignity, the question we need to ask is: has that dignity addressed the historical and contemporary forms of conjugated oppression that have interlocked Muslim labourers, indebted to their own extended family members as (Muslim) labour contractors? In that sense, while the question of dignity (samman) is important, it may not only obscure exploitation (shoshan), but also lead to the danger of normalising it and, in turn, encourage the possibility of ignoring the need to address exploitation.

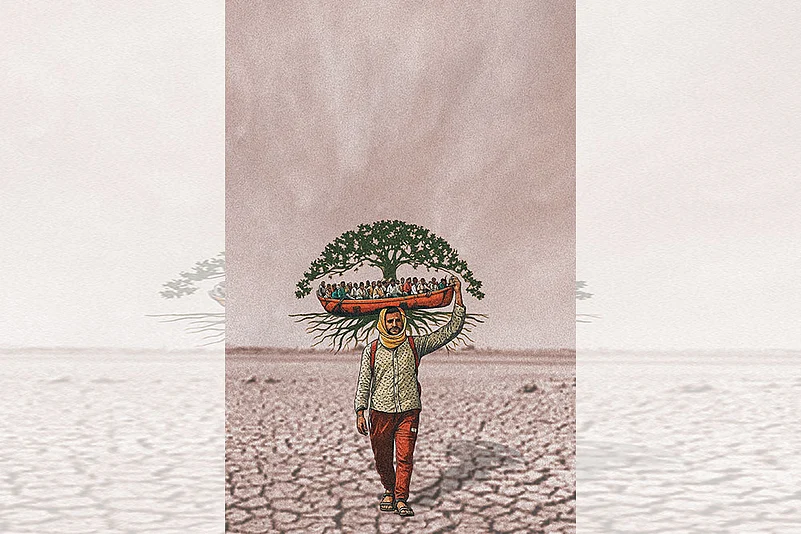

Emphasis on freedom remains a key component for Bihari migrants to be able to make safe and temporary journeys between their home villages and the places of work. However, their perpetual struggle in these journeys is a part of the wider patterns of social relations of exploitation, shaped by the thekedari system. As a result, what cannot be ignored is what happens at their workplaces in the cities, and whether the “freedom” of their mobility can transform class relations, can challenge their state of working permanently for their thekedar. Such freedoms may often invisibilise or otherwise insulate their majboori (compulsion) to work outside Bihar and concerns of the exploitative conditions of their majdoori at work.

While the more recent attention to industrialisation in Bihar is seen as a welcome move in allowing migrants to return to the state, one needs to examine if the structures and mechanisms of exploitation are simply brought back home under the lexicon of ‘return(ee) migration’ of Bihari labourers or whether Bihari labourers will be replaced by other cheaper forms of labour power who have similar working capacities. Moreover, a conversation on stopping migration from Bihar might seem like a possibility or even plausible—given the harsh realities of the lives of migrant labourers—but there is a need to think beyond saying “yes or no” to the act of labour migration to be able to bring the question of how labour migration from Bihar is (re)producing cheap forms of labour for global capitalism.

If the development of Bihar has been about good governance, social justice, and dignity, the realities of class-based experience of labour and the question of class-based injustice need to take centre stage. This is because class relations, which often remain hidden or otherwise accepted, cannot ignore other social relations of caste, gender, ethnicity, and religion. Practically, this may mean not just state engagement, but engagement with the thekedars and the employers (in this case, building companies) who work hand-in-hand to perpetuate the exploitative system. If Bihar continues to remain the labour hotspot in shaping the cheapest forms of labour, what are the possibilities of the emancipation of the Bihari working class, in using a collective mindset, to undercut the system of exploitation? This may mean looking at the possible occurrence of a Bihari migrant labourers’ episode of the recent Gen Z protests as a way to challenge the architecture of exploitation. That said, the politics of the state of Bihar will not be salient enough as long as it remains silent on the need to address the invisibilised system of exploitation of Bihari migrant labour, and until it engages with the question of class. The masses of Bihar need a fundamentally new conversation.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Manish Maskara teaches global development at SOAS, University Of London