Summary of this article

For most of mainland India, winter is a passing season and summer is when the year pauses. In much of the Northeast, winter is the cultural centre of gravity.

The problem lies in the assumption that a single model of time can be made to fit an entire country and that adjustments will sort themselves out at the margins.

A regionally sensitive academic year is not a concession but the logical outcome of federalism in a culturally diverse union.

On a cold December morning in Aizawl or Kohima, the town is already awake before the sun has properly risen. The church compound is littered with wax from last night’s choir practice. Youth groups have been rehearsing carols and lengkhawm for weeks. Relatives from Delhi and Bengaluru are finally home, sleeping under extra blankets in overcrowded houses. In the kitchen, meat is being marinated for community feasts.

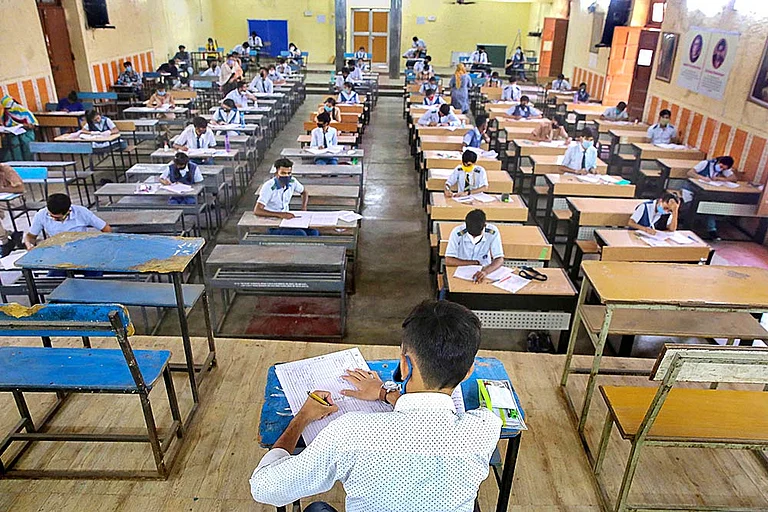

And somewhere in the middle of all this, a Class X student slips out with a bag full of textbooks, heading not for choir or convention, but for pre-board examinations.The cold bites, but the greater sting is the fear of missing what their town waits all year to become. The small act of walking past the church towards the examination hall is where two calendars collide. One is the old winter calendar of the hills: a season of gathering, ritual, memory and rest. The other is the new academic calendar, aligned with CBSE’s national timetable: exams in December or February, a short winter break and a long summer vacation designed for the climate and rhythms of the plains. The clash between these two ways of organising time is not just an inconvenience. It is a quiet reordering of what counts as meaningful life in the Northeast.

For most of mainland India, winter is a passing season and summer is when the year pauses. In much of the Northeast, it is the other way round. Winter is the cultural centre of gravity. It is when migrants come home, churches organise their largest gatherings, village-based festivals unfold and choirs and youth fellowships take over the evenings. It is when people have the time and mental space to sit together, reconcile old disputes and renew dense networks of obligation and care.

This is especially true in Christian-majority hill states like Mizoram and Nagaland, in the hill districts of Manipur and in many parts of Meghalaya. Here, December and early January are not stray festival dates dotted across an academic year. They form a continuous social season, beginning with late autumn festivals and peaking with Christmas, New Year and church conventions. The idea that this period can be reduced to a brief “winter vacation” is foreign to how people actually live.

Yet, that is precisely what is happening. State boards and private schools across the region are being drawn, almost inexorably, into the orbit of the CBSE calendar. Academic sessions begin in April or January, exams are bunched into February and March and final tests or pre-boards creep into early December. Winter breaks shrink into tightly defined windows, enough for a few major services and perhaps a family dinner, but not for the long, unhurried season that communities are accustomed to.

On paper, this is described in neutral terms: alignment, standardisation, uniformity, competitive parity. It is easy to accept this language if one is far from the hills and imagines the Northeast only as a set of districts on an administrative map. But look at the lived reality and a different picture emerges. A Mizo or Naga child now writes crucial exams in the days leading up to Christmas. Students in Manipur’s hills move straight from year-end papers into compressed festivities, before being pulled back into a new term that starts almost as soon as the fireworks die out. Schools in parts of Meghalaya are warned against declaring local winter holidays without clearance, as if the festive season were an indulgence rather than a structural feature of social life.

The problem is not that CBSE officials lack empathy, or that the National Education Policy, in the abstract, is hostile to diversity. The problem lies in the assumption that a single model of time can be made to fit an entire country and that adjustments will somehow sort themselves out at the margins. A national calendar that appears reasonable in the plains becomes an instrument of distortion in the hills.

Calendars are not neutral devices. They are expressions of power. In the Northeast, the calendar functions as the state’s most silent boundary drawn not on land, but on time itself. To decide when children study, when families may gather, when rituals can be held without penalty, when teachers can pause, when communities may rest, is to decide whose world is being honoured. A calendar answers, in quiet but decisive ways, the question: whose time counts?

In India, the default answer still comes from the climatic and cultural rhythms of the North Indian plains. Summer is long and intolerable, so it becomes a vacation. Winter is short and workable, so it becomes exam season. Once that pattern is fixed at the national level, any community whose life is structured differently is treated as an exception. Those exceptions may be recognised in circulars and guidelines, but the centre of gravity never shifts.

This is what makes the reorganisation of school calendars in the Northeast so revealing. States are not simply choosing dates on a blank slate. They are reaching for a template that already carries a normative force. When Mizoram compresses winter into a few weeks and pushes its longest holiday into March; when Manipur schedules crucial examinations in December and begins new sessions in January; when Nagaland ties its academic calendar tightly to centrally driven exam windows; when Meghalaya insists that even church-centric winter breaks be vetted through official channels—each of these choices is made under the shadow of a national model that is tacitly treated as superior.

The irony is that the Northeast does not have a single cultural calendar of its own. It is one of the most heterogeneous regions in the country. A church-based society in Aizawl does not have the same rhythms as a Garovillage, whose winter dances mark agricultural transitions, or a Tangkhul community whose festivals are woven into ancestral histories, or a Khasi household for whom Christmas is entangled with clan obligations and return migration. Yet, despite this diversity, there is a rough convergence on one point: the thickest part of collective life lies in the winter months.

Trying to force these varied worlds into the mould of an April–March academic year, with short winter breaks and standardised exam windows, is not merely a matter of convenience. It narrows the space for cultural sovereignty. A region that cannot decide the shape of its own year is a region whose priorities have been quietly subordinated. When winter is reduced to a short, negotiable holiday between exam cycles, the state is effectively saying: your season of gathering and worship may continue, but only within the margins that a distant timetable allows.

This is cultural invasion at its most understated. It does not announce itself with hostility. It arrives instead through circulars, examination schedules, affiliation rules and the prestige of certain boards. It speaks the language of merit and modernity, not domination. But its effect is to centralise time itself. The language of governance that accompanies this process still imagines the Northeast as an object of management. Policy is written as if it must travel from the Centre outward, with adjustments made where resistance is too strong. The idea that policy could be co-authored, that the region could shape the very template of the academic year, is rarely entertained. Delhi governs over the Northeast, not with it.

A more demanding vision of governance would begin from the opposite end. It would ask: what does winter mean, in concrete terms, for communities across these hills? How much time do churches actually need to organise their conventions and choral gatherings without crushing children under competing obligations? How do agricultural cycles intersect with school attendance? What do landslides and monsoon disruptions do to teaching days? Only after those questions are seriously addressed does it make sense to talk of alignment or standardisation.

If the Centre is serious about cooperative federalism and cultural respect, the academic calendar is a relatively easy place to demonstrate that it listens. No constitutional amendment is required. No grand institutional redesign is needed. It simply demands a willingness to accept that time in India is plural and that national systems must adjust to that plurality rather than flatten it.

A regionally sensitive academic year is not a concession—it is the logical outcome of federalism in a culturally diverse union. One can easily imagine a different model. The Northeast could have a regionally adapted academic year that begins later or earlier, ends differently and anchors itself around the winter season rather than treating it as a suspension. Exam schedules, especially for final years, could be negotiated so that December is not turned into a high-stakes test corridor. Practical exams could avoid festival weeks in states where the social calendar makes that intolerable. Working-day requirements could be calculated over a wider window, taking into account both monsoon disruptions and winter obligations. State boards could be given explicit space to design calendars that emerge from local consultations with teachers, parents, church bodies, and community organisations.

None of this reduces educational rigour. If anything, it strengthens it. Children learn more meaningfully when the institution of schooling does not stand in permanent tension with the rest of their lives. A school that respects the community’s calendar is not capitulating to tradition; it is recognising that education cannot be built on the humiliation of cultural forms.

Standardisation does have its place. National exams, shared benchmarks, and certain synchronised processes are useful in a large, mobile society. But when standardisation becomes a reflex, it turns diversity into a logistical nuisance. It privileges one rhythm of life over another and then pretends that the hierarchy is natural. It asks some societies to compress their time so that others may keep theirs intact.

In the Northeast, winter carries the emotional weight and cultural density that summer carries elsewhere. When a child must choose between a pre-board exam and participation in a church convention that has shaped their family for decades, the loss is not merely personal. A festival truncated for the sake of a timetable loses part of its meaning. A ritual squeezed into a spare weekend becomes another programme to be “adjusted” around work. Over time, the erosion is cumulative.

A plural democracy cannot afford that kind of erosion. The strength of India lies in its capacity to hold multiple calendars and still recognise them as equally legitimate ways of inhabiting time. In the end, the question is simple, even if the implications are not: whose time counts? If the answer remains that only the Centre’s time is real, then the Northeast will continue to be governed as an administrative frontier expected to fall in line with schedules drawn elsewhere, its own seasons treated as interruptions. If, however, the state is willing to see the region as a partner in shaping policy, then respecting the winter calendar becomes something more than a gesture. It becomes a small but concrete act of political maturity.

New Delhi does not need to govern the Northeast upward, correcting it from a distance. It needs to govern with the region, listening to its seasons, sharing authority over something as basic as the school year, accepting that a calendar is not a neutral ledger but a record of how a people chooses to live. When the state finally treats cultural time as seriously as administrative time, the sense of estrangement that has long haunted the hills may begin, slowly but surely, to recede. Only then will the Northeast recognise itself in the nation and the nation recognise the Northeast on its own terms.