Summary of this article

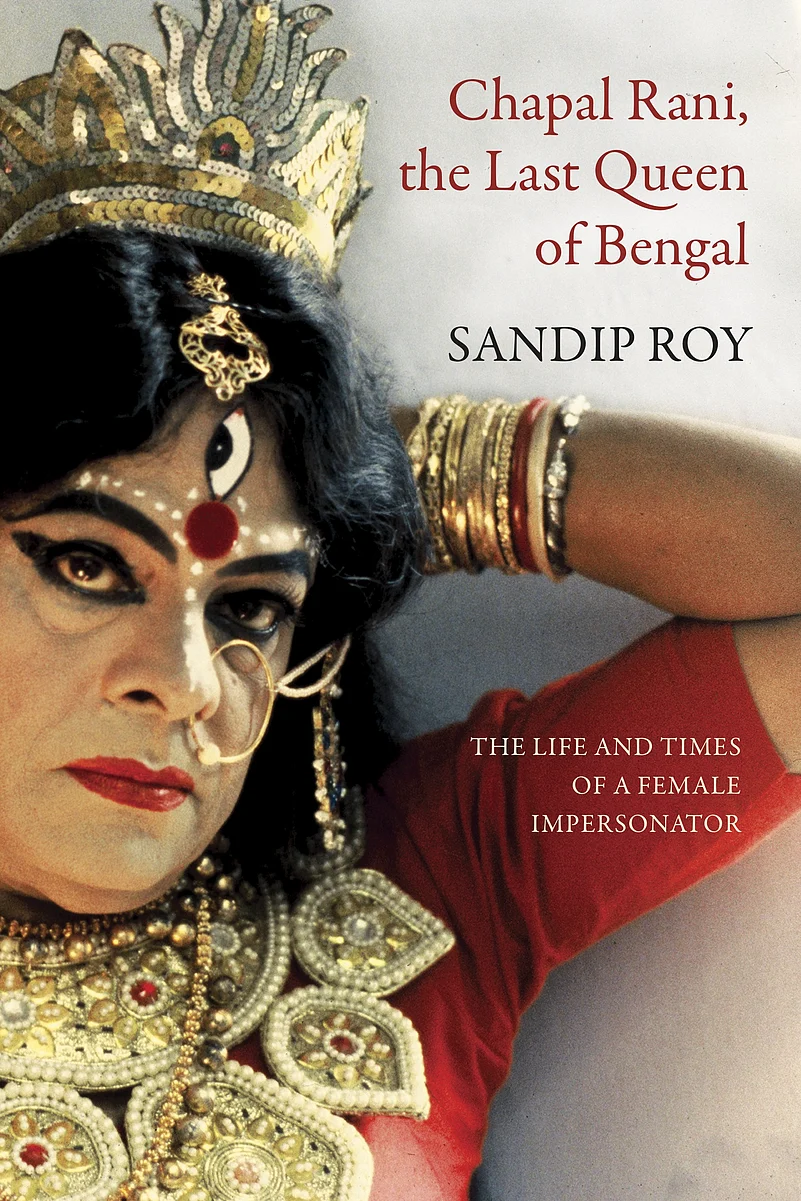

Published by Seagull Books, Sandip Roy's latest book Chapal Rani is an evocative biography.

The book is about Bengali stage actor Chapal Bhaduri.

Roy has previously nominated for the 2016 DSC Prize for his debut novel Don’t Let Him Know.

It was a full house, our home at 13/1C Dalimtala Lane, the house where we moved to from the three-storied red house on Balakhana Street. Our new home was not far from the street where legendary actress Nati Binodini lived out her last days. Her house is still there, a small green two-storied affair with a very narrow balcony and a plaque out front bearing her name. It looks like a house a child might have drawn in art class. I never saw Binodini, but Ma would tell us stories about going to visit ‘Binod-ma’.

The narrow streets of North Kolkata were full of mansions and palaces, with columns and arched windows, where Burma-teak doors led into great inner courtyards. Our street was nothing like that—it now has boxy apartment buildings all along it, noisy roadside temples, beauty parlours with neon signs alongside old-fashioned tea shops and a dry cleaner named Snow White. The city council has put up busts of great social reformers like Ishwachandra Vidyasagar and Raja Rammohun Roy and stuck some ornamental plants behind bamboo fences to create an illusion of little pavement gardens.

When we lived there, it was just cow sheds. The whole street smelled of cowdung or gobar, and that’s why the area was named Goabagan. During the monsoons, when it rained torrentially, a smelly brown river of cow dung flowed down the street. Our house was set back from the street, off a narrow lane. It was a three-storey house but very cramped, squished onto just 14 chhataaks of land. In those days, we measured land in chhataaks and kathas, a chhataak being about 45 square feet. Now I feel rather suffocated when I go there. It seems to be without much light or air, hemmed in by buildings. But when I was little, it seemed big enough—three large rooms on the ground floor and a little bit of a courtyard. One room under the stairs, which was always pitch dark even in the middle of the day. That’s where we kept all our heavy metal pots and pans. Another small room, to store the coal we used for cooking. When I was naughty, my brothers would threaten to lock me in that dark room.

On the first floor, one big room and two smaller ones. My father and my sisters had their rooms up there. My brothers lived in the rooms on the top floor which also had a strip of a terrace where we would sometimes have sit-down feasts. At one time, one brother raised pigeons there. Ma would make pickles and put them out in the sun on that terrace. We never bought pickles from the store. Ma made them all at home. My favourite was the one where she took sour tamarind and sweet sugarcane jaggery, put it in little clay pots, tied the mouth tightly with string and then left it in the sun. Sweet yet tart, it tasted utterly delicious. Ma could pickle anything. Carrots, cauliflower, mangos, even drumstick stalks.

Prabha Devi’s Mixed Pickle

Take drumstick pieces and steam them till soft. Chop up cauliflowers and carrots into small pieces and steam. Stir them in a heated pan till completely dry.

Grind the following in a mortar and pestle (not a mixie) with a bit of vinegar—cumin seeds, ginger, garlic, chili powder, turmeric powder. Add oil to the pan, add the spice paste and stir fry it. Then sauté the vegetables. Add more vinegar if needed. Stir fry till well blended. Finally heat mustard oil (remember, you cannot do this with unheated oil) and pour it into a glass or ceramic jar. Add the vegetables and keep for a couple of days till the vegetables become soft and tart. We called it Madrasi pickle though I have no idea why.

When I came to this old-age home, they first gave me a room on the roof, a room with a tin roof. I remember thinking: once we used the terrace to make pickles. Now it is my time to get pickled. My niece said: you cannot stay in this room. It might be all right in the winter but in the summer you will go mad.

Our house rent was 40 rupees per month. One day, a local contractor told Ma, ‘You keep paying rent on this, Prabha-di. Why don’t you buy it outright? I think you will get a good price.’ So, in 1950, Ma bought the house for 14,000 rupees and then renovated it entirely. She made a room for herself downstairs and painted it in ‘blue distemper’ colour. In those days, you could get a kind of bulb called Philips Moonlight. It was a pale blue but emitted a really bright light. Ma loved those bulbs. Ma might not have been very educated but she had great taste. Every day, after she came back from the theatre, she loved to spray rosewater on her face. She had intricately embroidered Kashmiri shawls, and liked to get her saris from a weaver named Nandalal whose Dhaniakhali saris were all the rage in those days. She did up the house, and she did it all on her own money.

Aside from our large family, there were some people I didn’t know who also lived in our house. I once asked Ma ‘Who are these people? They live here and eat our food day after day.’ She said, ‘These people were great actors at one time. Now their time is past. They are here for a bit. As soon as something comes up, they will leave. Why do you ask?’

‘Just like that, I was curious,’ I replied.

Ma grew grave. ‘I am noticing you have a lot of curiosity about things, Tuku. (My nickname was Tuku. When my mother really wanted something from me she added another letter and called me Tuklu.) Too much curiosity is not good. You be careful.’

I must have been eleven or so at that time.

* * *

Finally, Independence came to India in 1947. But before that there were such terrible riots. I saw one man hold another by the throat and hack off his head off with a chopper on Sahitya Parishad Street. The head remained in the hacker’s hand. The body jerked and twitched for a few moments, like a headless chicken. I have seen all this with my own eyes. I would raise the shutters of the window and peep through them. Everything still burns bright in my memory.

Ma though was a fearless woman. She would always carry a heavy silver box with her name, Prabha, inscribed on top. It had everything she needed to make her paan, her chief addiction. Sometimes I would wonder if she felt scared coming back alone, after dark, across the empty fields near our house. But she would scoff ‘Why should I be afraid? If anyone tries to do anything, I’ll knock their eyes out with my silver box.’

But the woman who was ready to knock robbers cold with her silver paan box was terrified when the riots broke out. We were a Hindu family in a Muslim neighbourhood. There was a mosque right next to our house. It was so close, I could see them offer namaaz from my window. I even knew the azaan by heart. When the azaan sounded early in the morning, it felt kind of romantic. The mosque was so close, the maulvi would stand on its terrace and pass us all kinds of treats on special days. The maulvi told Ma ‘Ma, do not fear. If we both stand firm against the riots, no one can touch us.’ But everything was in such chaos and the atmosphere so tense that Ma decided we had to go take shelter in my uncle’s Srirangam theatre. So she stuffed all her jewellery, her bankbooks, her important documents and her money in pillows and stitched them shut. Then she told us ‘Get hold of a stretcher, the kind they carry dead bodies on.’ She spread a blanket on the bamboo stretcher and lay on it, clutching the pillows, as if she was very sick. She said, ‘Let us go to Srirangam theatre. The police station is right next to it. We’ll be safe there. Don’t make too much noise or cry or draw too much attention. If anyone asks what’s happening, tell them our mother is sick, she is feeling very claustrophobic in the house and finding it hard to breathe. So we are going to Srirangam theatre.’

Srirangam was barely a five to ten minutes walk from our house and right next to the Battala police station. The officer-in-charge, a Muslim man, was a friend of my uncle’s. But Ma was terrified of walking with all her jewellery when the air was thick with stories of riots and carnage. It was hard to trust anyone in those overheated days. When we reached the theatre, we were hastily ushered in. Once we were safely inside, Ma sat bolt upright and cried ‘Hurry, tear open the pillows!’ Now it feels funny but at that time no one laughed.

Srirangam had been set up by the great theatre actor Natyacharya Sisir Kumar Bhaduri. My father Tara Kumar Bhaduri was his younger brother.

I remember it well. Four steps from the pavement led into the building with two large rooms, one of which served as a booking counter and the other as an office. There was a wide passage between them lined with wooden benches. There the Bhaduri brothers and their friends would sometimes sit and chat over endless cups of hot milky tea. The passage opened out onto a beautiful garden filled with flowers which was my uncle Sisir Bhaduri’s pride and joy. The audience would walk through this garden, past hedges of mehendi flowers, to reach the main auditorium. There was a huge oleander shrub and a night-blooming jasmine that smelt divine when it blossomed during the monsoon. It made for a magical walk into the auditorium. I used to steal plants from that garden for our own rooftop till one of my uncles caught me red-handed.

In the theatre compound was another house, which we called the ‘inner house’, where all the Bhaduri brothers had their own rooms, though Baba spent most of his time at our house. My uncle Sisir Bhaduri assigned a room to us on the ground floor. We stayed in Srirangam theatre for several months. One day, my uncle removed the seats from the auditorium so that the military who had come to quell the riots could camp there. I do not think any other theatre did that.

But on Independence Day itself there was so much celebration. At midnight we were all listening to the radio. There were firecrackers going off everywhere. In the morning, all the shops, theatres, even people’s homes were decorated with strings of little tricolours printed on paper. Children went to school and drew alpona patterns on the floor. People cooked up great feasts at home. After all, the country does not become independent every day.

Sandip Roy, a Kolkata-based writer and longtime radio voice, hosts dispatches on KALW and writes a regular column for Mint Lounge. His debut novel Don’t Let Him Know was longlisted for the 2016 DSC Prize.

Excerpted with permission from Seagull Books