The poems in this collection remind that many find freedom in the urban sprawl of an Indian city.

Charles Baudelaire once said, the city changes form, often faster than the human heart.

That is how the urban sprawl finds space in poetry, for to each poet the same place is different.

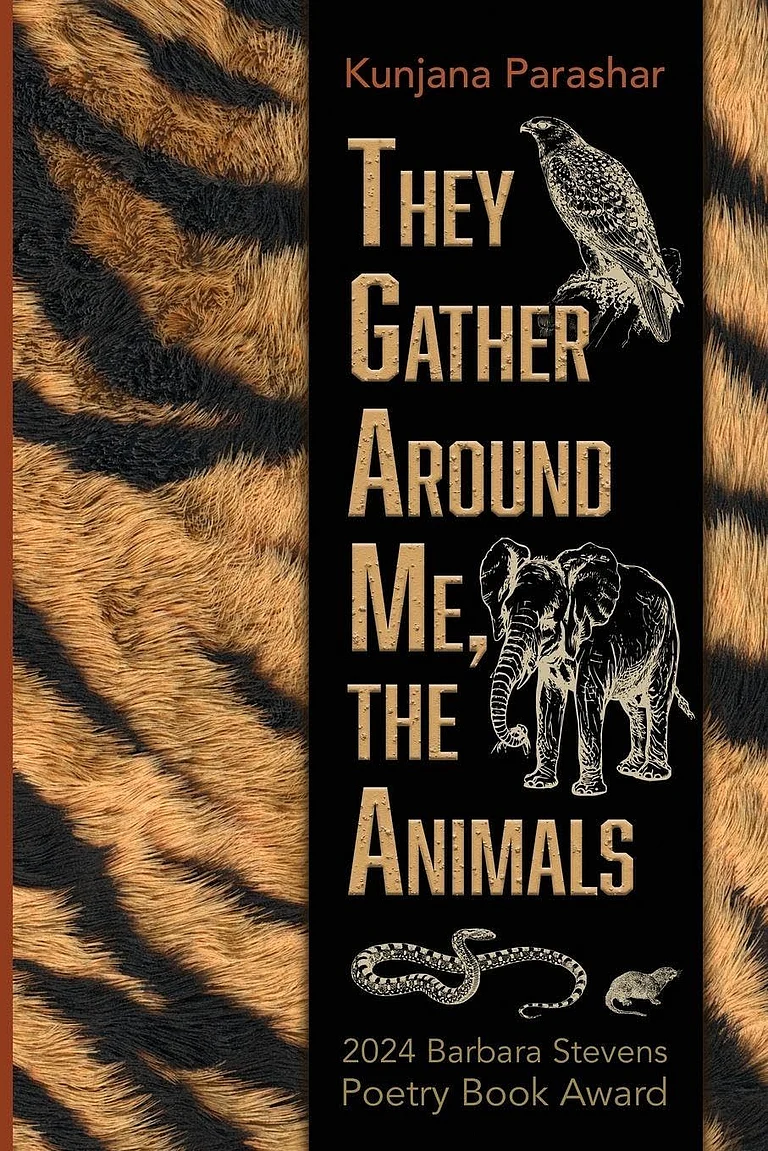

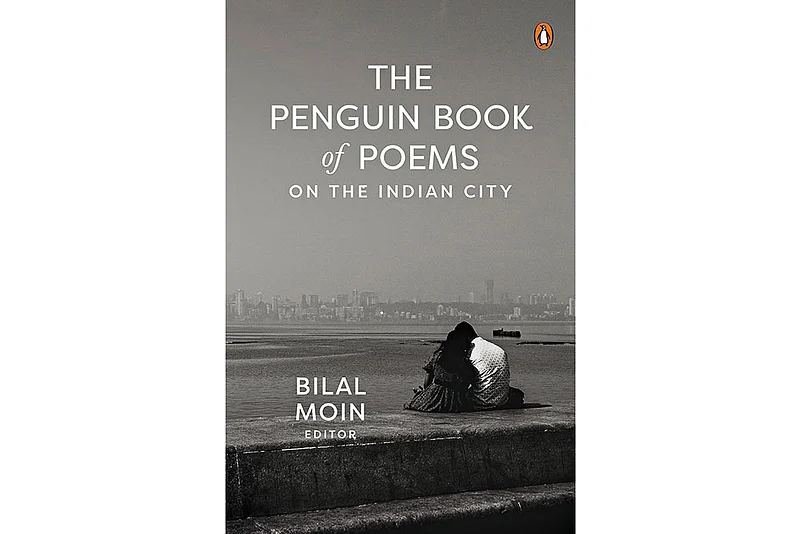

India has six mega cities with a population of over ten million; Mumbai and Delhi are two of the ten largest cities in the world. Mass migration to cities carries on like a river in spate. If ever there was a moment to map the contours of the Indian urban experience—its history and geography, its emotional resonance—it is this. And what better means than poetry to immerse ourselves in the voices that animate Indian cities, the lives that populate their busy streets and narrow lanes? Thirty-seven Indian cities via 375 poems: readers get to journey across them in The Penguin Book of Poems on the Indian City (Ed. Bilal Moin). This collection includes poems translated from 20 Indian languages as well as those written in English. Anthologies of city poems from across the entire country are a rarity. This vibrant mosaic is a gift readers will cherish.

Charles Baudelaire, poet and perennial wanderer (flâneur as the French would put it), lamented: “The form of a city changes faster, alas, than the human heart.” Yet, poets have always been intrigued by cities. The urban experience is grist for the poet’s mill: the city’s tender turns and ruthless games; the manic rhythms; the mysteries cloaked in smog and grime. But are all cities essentially the same? You’ve seen one you’ve seen them all? Do Indian cities have a quintessential ‘Indianness’? Does a common thread run through all of them? Reading this collection is an enjoyable way of searching for the answers.

Here, poets walk us through many Indian cities, big and small. We head east, west, south, north. We see cities through the eyes of sixth-century bards; we hear what poets born in the 21st century have to say about them. We hear the names cities were born with, the names they’ve grown into, the names imposed on some. We hear the cadences of Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Marathi, Manipuri, Urdu, Hindi, Bengali, Gujarati, Kashmiri...For one poet, his city is “an atlas of lost things” (Siddharth Dasgupta); for another, it is the home where a people made homeless by the Partition “reknotted themselves” (Adil Jussawalla). It is the place where a houseboat floats, learning it is just “a pawn on a chessboard”, learning the “art of being irrelevant” (Asiya Zahoor). It is the lonely planet that has “lost its head”, where “none has time for anyone else” (Debi Roy, trans. Manish Nandy). It is where the poet rides a crowded local train, musing, “When I descend/I could choose/to dice carrots/or a lover” (Arundhathi Subramaniam); the bookstore-lined home from where “neglected rebels offer a dog-eared laal salaam” (Nandini Sen Mehra); the arena where “houses with sculptured features” and “sculpted hills” tussle (Saratchand Thiyam, trans. Robin S. Ngangom).

Each poet is fascinated by their city’s specificities. Kolkata’s tramlines; Kalahandi’s blood and tear-stained streets; Chennai's savoury air; Hyderabad’s bustling bazaars; Haridwar’s ghats; Delhi’s medieval ruins; the shikarawallahs’ song wafting over the Dal, the skies stretching over Bangalore, dotted with clouds of dreams and smoke. These poems lay bare what the city does to you. Poets write of the cities they were born in, the cities they were exiled from, the cities they pass through as visitors.

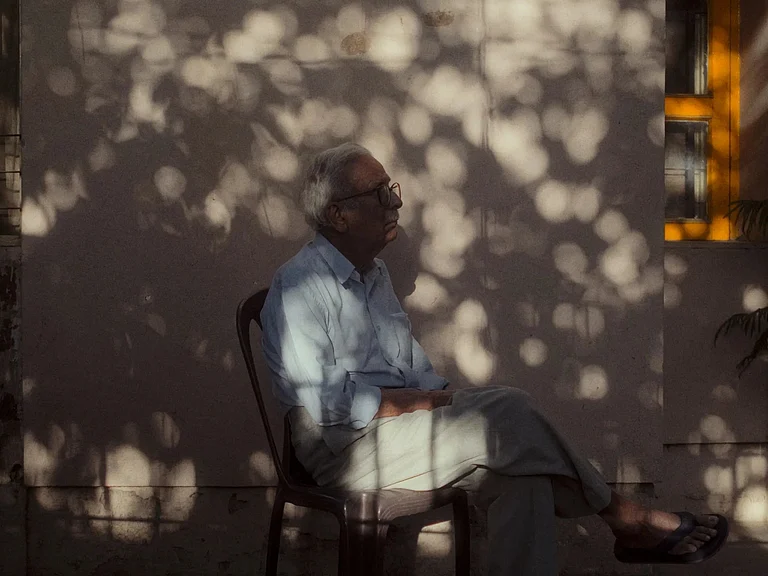

In his Introduction to the collection, Moin says that for poets who are lifelong residents of a city, poetry becomes the “medium through which they articulate the lived experiences of the city—its walks and commutes, its places of study and work, its moments of love and inevitable disdain.” Nissim Ezekiel, whose allegiance to Bombay was steadfast, swore, “I cannot leave the island/ I was born here and belong.” Birth doesn’t guarantee belonging though. Not all poets feel at home in their cities of birth. To some, their home remains a lifelong puzzle, an enigma they can never fully decode.

Lifelong resident, aching exile, or passing visitor, the poet takes in everything the city has to offer. Beauty, horror. Hope, desolation. Riots, curfews, chaos. Rags-to-riches stories. Rotting dreams. Skyscrapers, seaside cafes, chimneys belching smoke. Local trains chugging along, their crammed insides haunted by questions of caste and faith. The roar of traffic, the hum of the azaan. Golden-domed gurdwaras. Gardens, parks, fountains. Walled cities, ruined cities, old cities overwhelmed by nouveau riche spectacle. The city plays muse to the poet; the poet’s words give the city shape and form. City dwellers are subject to the city’s whims. But they also shape the city in their own subtle and not-so subtle ways.

The way time has shaped and reshaped Indian cities is a fascinating thread to follow. The poems in the collection, which cover a span of 1500 years, capture the transformation of ancient cities such as Kashi and Madurai, and the growth of modern urban centres such as Bangalore. “Each poem, shaped by its time, contributes layered depictions of cities…” Moin says. Together, they form “an archive of the literary, temporal and spatial continuum of Indian cities.”

The poems serve as reminders of the fact that many find freedom in the urban sprawl of the Indian city. The anonymity the city promises, for better or worse, is something villages cannot offer. Plenty of marginalised voices have made their presence felt in city poetry, challenging societal and literary hierarchies, sharing their everyday experiences in verse. In Dalit poet and activist Namdeo Dhasal’s Kamatipura, “death gathers…as do words”. In Jayanti Makwana’s Keshav Ganda Bhangi, glimpses of Keshav’s life of servitude in Ahmedabad-Amdavad tells readers that freedom in the city remains the preserve of the chosen few. More than a few poems in the collection grapple with urban poverty and its debilitating impact on human lives. Some poets are haunted by the fate of migrants, whose backbreaking labour builds the city and keeps it running, but are neither rewarded or recognised for it.

In City of Women, Linthoi Ningthoujam addresses all the women she has met in the city, their “migrant hearts slung on slender shoulders/looking for a ground to stand and perhaps, speak”.

She calls out to them: “Our towns have never understood us…Tonight, let us be wantons together/let us reclaim our caged tongue.” Uma Rajiv too finds the Indian city a male-dominated space where women keep fighting a daily battle to be treated as equals. In So Disappointing (trans. Ra Sh), Rajiv notes: “If you stand around in some big junction/Or crossroads of the city/About to turn into/A Metro/You can see/Many kinds of male heads…/Eyes/Wandering”.

Unequal balance of power, unbridled industrialisation, the blind quest for progress at the cost of the vulnerable; cruelty, kindness, chaos, conflict; bursts of violence, flashes of tenderness, glimpses of beauty—the poems embrace the many contradictions of Indian cities, urging readers to experience them fully. This collection is a remarkable travelogue across time and space, across a vast, diverse country that is bigger than the sum of its parts. Definitely a journey worth taking.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Vineetha Mokkil is Associate Editor, Outlook. She is the author of the book A Happy Place and Other Stories