Summary of this article

Sales are growing, young readers are returning in significant numbers, and Indian publishers are taking risks

Adaptation, not nostalgia, has kept readers engaged

The steady growth of independent bookstores suggests that readers are not just buying books—but returning to them

“Reading is dead” has become one of culture’s most confidently repeated claims—invoked every time attention spans shrink, screens multiply, or a new platform goes viral. Streaming has eaten time, reels have trained impatience, and bookstores are often spoken of as relics kept alive by nostalgia.

And yet, across publishing houses, bookstores, and literary ecosystems in India, the data and daily experience tell a different story. Sales are growing, regional languages are thriving, young readers are returning in significant numbers, and publishers are taking risks that would be impossible in a truly declining market.

From Malayalam fiction clocking print runs that rival global bestsellers, to Hindi publishing that spans six generations of writers, to English-language imprints commissioning queer romance and rediscovering literary fiction, Indian publishing today is not fighting for relevance. It is quietly reshaping what reading looks like in an age of distraction.

The Malayalam Story

“The Nielsen BookScan report says it all,” says Ravi Deecee of DC Books. “Malayalam books have been consistently trending in national lists. In fact, apart from English, Malayalam is the only Indian language that has featured continuously at the national level.”

That visibility is not accidental. The literary ecosystem in Malayalam is deep, commercially confident and globally connected. “The JCB Prize for Literature further underscores this vibrancy: out of the last six awards, three have gone to Malayalam works translated into English, reflecting the extraordinary strength and depth of the language’s literary culture. And in the other three years also Malayalam was in the shortlisted titles,” informs Deecee.

What truly unsettles the idea of a dying readership is scale. “Literary fiction also enjoys remarkable commercial success in Malayalam. Many major titles begin with first print runs of 10,000 copies and often go up to 25,000. Our recent release, Kalachi by K.R. Meera, was launched with 25,000 hardcover copies priced at ₹599 is an indicator of the confidence and scale of the Malayalam reading market.”

The Pandemic Changed Reading

“Reading has seen a significant rise since the pandemic,” Deecee says, pointing out that DC Books responded with “highly innovative marketing strategies,” many of which were documented during lockdown. What followed was not a post-pandemic crash but an expansion.

“In the post-pandemic period, this momentum has translated into concrete growth: new stores across Kerala, increased sales, and expanded formats, including audiobooks and eBooks, which have especially helped us reach the global Malayalam diaspora.”

The most persistent anxiety around reading is about young people. Here too, the numbers tell a different story. “Youth have been brought into reading through a range of focused campaigns. Ram c/o Anandi by Akhil P. Dharmajan, a true Gen Z novel, has sold over 400,000 copies so far and remained on the Nielsen BookScan chart for almost 12 weeks.”

Adaptation, not nostalgia, has kept readers engaged. “We have introduced micro-fiction formats to cater to the interests and shorter attention spans of newer readers. At the same time, upmarket fiction, thrillers, and fast-paced narratives are increasingly becoming part of their reading preferences.”

Even production has evolved. “Print production has undergone a major transformation with the adoption of short-run printing. This has been a game changer. We now handle over 200 reprints a month through short-run technology, ensuring faster availability and drastically reducing stock outs.”

Online growth hasn’t cannibalised physical stores either. “Online sales have grown nearly tenfold post-pandemic, even as we successfully retained, and strengthened, our brick-and-mortar performance.” And in a telling contrast to English publishing, “Malayalam publishing also shows a distinctive trend: new titles often become bestsellers, in contrast to English publishing, where backlist titles dominate.”

Hindi Publishing and the Long View

For Ashok Maheshwari of Rajkamal, the idea that reading is dying feels particularly ahistorical. “We have been working with six generations of writers. On one hand, the second and third generations of older writers remain in touch with us; on the other, we consistently publish the very first books of the youngest generation of Hindi creativity.”

Publishing, here, has always responded to social need. “At that time, we were publishing books on the freedom struggle, patriotism, Mahatma Gandhi, agriculture, social sciences, military science, photography — subjects society needed.” The list of writers Rajkamal has published across decades reads like a map of modern Hindi intellectual life: “Romila Thapar, Ram Sharan Sharma, and Irfan Habib… Agyeya, Mohan Rakesh, Kamleshwar, Bhisham Sahni, Mannu Bhandari, Rajendra Yadav, Nirmal Verma.”

The present moment, Maheshwari suggests, is no less significant. “Recently, we organised a major and significant event titled ‘The Year of Women’s Hindi Novels.’ For the first time in any language, nine important novels by nine women writers were released together. We consider this century to be one of the flourishing of women’s writing.”

If readers were disappearing, such interventions would not be possible—or sustainable.

The Myth of the Bestseller Obsession

Speaking Tiger started as a modest initiative in 2015, but its catalogue has grown to over 700 titles across genres and geographies and founder Ravi Singh offers a quieter but equally persuasive rebuttal to panic-driven narratives.

For Singh, faith in readers is foundational. “If I and my colleagues like a book very much, it is inconceivable that there won’t be at least a few thousand more who will also like it.” The goal, he insists, isn’t chasing viral hits. “Who doesn’t want bestsellers? We dream of them. But not every book can or even needs to be a bestseller.”

Instead, the focus is durability. “I’d rather we try harder to ensure no book we publish is a dud than to focus on making just a couple of titles bestsellers and in the process neglect the remaining 99 per cent.”

Technology, here, enables risk rather than caution. “Targeted online marketing and sales are making it possible to reach more readers, and readers with different interests and beliefs. Shorter first print-runs combined with print-on-demand reprints are also helping us take greater chances with newer voices, or revive brilliant yet neglected older ones.”

But Singh is wary of neat conclusions. “I’m always suspicious of reading habits—these keep changing and they often replace one dominant discourse with another. If we’re going to be an alternative, we need to look beyond the mainstream, or at least look at it from a different angle.”

Independent Publishing and the Evidence of Loyalty

That confidence is echoed by Deepali Trehan, Sales Head at Tara Books, whose experience complicates the assumption that only mass-market publishing is surviving. “Numbers speak for themselves, and we see readership and loyalty sustain over the years, with titles in both our handmade and children’s books segments doing equally well,” she says.

Crucially, this loyalty is not confined to niche collectors or international audiences alone. “The Indian market has consistently done well and seen improvements year on year,” Trehan notes, challenging the idea that serious or design-led publishing depends primarily on overseas validation.

What is most telling, perhaps, is where that confidence is becoming visible. “We supply to stores directly across the world and the confidence for book readership is evident in independent stores expanding,” she says, “especially in India.” In a climate where retail pessimism is often treated as cultural truth, the steady growth of independent bookstores suggests that readers are not just buying books—but returning to them.

Reading as Resistance to Distraction

If shrinking attention spans are the anxiety driving the “reading is dead” narrative, Sanghamitra Biswas of Pratilipi argues that the same anxiety may, paradoxically, be pushing people back to books. “People are more aware than ever of shrinking attention spans and a general lack of ability to focus. Reading is the obvious antidote so I believe people are actually trying to read more,” she says.

That impulse is showing up clearly in what readers are choosing. “We’ve seen that reflected in the sales of translated works. Readers are keen to discover classics in different Indian languages.” The hunger, Biswas suggests, is not just for entertainment but for orientation. “In non-fiction, people are reading books on history, identity, politics, books on self-improvement … basically books that better their understanding of themselves and the world.”

What is especially striking, she adds, is that literary fiction—often presumed to be the most vulnerable category—has not withered. “What’s especially heartening is that the small and carefully nurtured space for literary fiction is thriving too. Despite challenges of discoverability, there have been more than a few remarkable debuts.”

This confidence extends across generations of writers. “We are publishing the new novels of established authors as well—Mirza Waheed’s new book, Maryam and Son will be out soon, Jane Borges, whose Bombay Balchao was a cult classic, will be publishing her new book in 2026.”

New Readers, New Stories

At Penguin Random House India, scale itself challenges the idea of decline, with hundreds of new titles every year, partnering with businesses that sell millions of books annually in India.

As Senior Commissioning Editor Archana Nathan points out: what’s changing is not the existence of readers, but what they want to read. “I think there is a sizeable audience in India that is quite keen to read desi queer romance fiction in particular,” Nathan says, noting that global trends are feeding local confidence. “The popularity of Heated Rivalry and queer romantic titles from the US is definitely encouraging us to commission more books in this genre.”

The response has been concrete. “In fact, this February, we are publishing an exciting queer rom-com called Queerly Beloved by Farhad Dadyburjor. It’s a story of the big fat Indian wedding of Ved and Carlos, who have to navigate everything that goes wrong in order to get to their big wedding day. It promises to be a very fun read!”

If publishers track intent, bookstores witness behaviour. For Aakash Gupta of Crossword, the continued relevance of the Crossword Book Awards offers a clear rebuttal to the idea that reading culture is fading.

“The continued relevance and popularity of the Crossword Book Awards is, in my view, a strong signal that reading culture in India is not only alive, but evolving and deepening. These awards attract serious attention from authors, publishers, readers, and the media because books still matter, as ideas, as conversations, and as cultural markers.”

Gupta argues that the oft-repeated claim that nobody reads anymore stems from a basic misunderstanding. “The idea that ‘nobody reads anymore’ usually comes from confusing how people consume content with whether they engage deeply.” What is becoming visible instead, he says, “especially among younger readers, is a renewed appreciation for long-form thinking.” He points to growing awareness, supported by research, that “sustained reading builds empathy, improves focus, and shapes how we think and process the world. Books do something to the brain that short-form content simply can’t.”

Far from being obsolete, the physical book has acquired a new kind of relevance. “At the same time, we’re living in an age of digital fatigue. Many people are actively seeking digital detox—ways to step away from constant screens and notifications. The physical book has become a powerful antidote to that. In that sense, books today are not competing with technology; they are offering relief from it.”

Ironically, technology has also widened access. “Social media has also helped reading. Platforms like Instagram and YouTube have created vibrant book communities where readers discover, discuss, and celebrate books. That visibility feeds curiosity and aspiration, especially among young readers.” The awards, Gupta notes, both draw from and strengthen this ecosystem by “spotlighting quality writing and reminding us that reading is still aspirational and meaningful.”

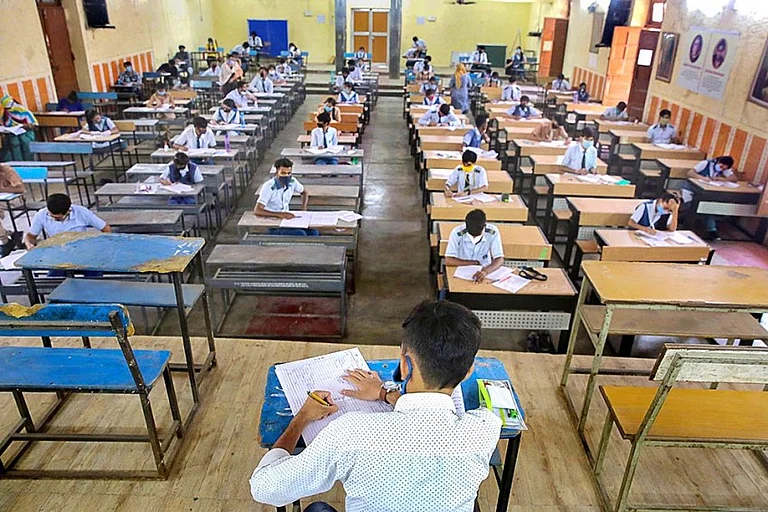

On the ground, the evidence is unmistakable. “What we see both in our stores and at book fairs strongly challenges the idea that people don’t buy books anymore.” Walk into a Crossword store or a major book fair, he says, and “the spaces are full, and they are full of young people.”

Sales patterns reinforce this reality. “Families are buying children’s books in large numbers, young adults are exploring fiction and non-fiction, and readers are open to discovering new authors and genres.” Book fairs, in particular, have become “cultural events—places where people don’t just shop, but browse, discuss, and spend hours engaging with books.”

Most crucially, Gupta reframes what reading looks like today. “What’s important to understand is that reading hasn’t disappeared—it has diversified. Readers today are more intentional. They may consume short-form content online, but when they choose a book, they are committing time, attention, and money to it. That’s a powerful form of engagement.”

From the vantage point of scale, the trend is clear. “From everything we see as a retailer operating at over 130 stores across cities and formats, the trend is clear: physical book buying in India is not declining—it is steadily growing, driven by younger readers, families, and a broader cultural shift toward depth, meaning, and mindful consumption.”

The claim that reading is dying persists because it sounds intuitively true in an age of distraction. But across languages, regions, publishing philosophies—and now, retail floors—the evidence points elsewhere. Readers have not vanished; they have diversified. Formats have multiplied. Risk has become possible again.

If anything, Indian publishing today looks less like an industry in decline and more like one shedding old hierarchies—between “serious” and popular, regional and global, literary and commercial. The book, it turns out, isn’t fighting for survival. It’s simply finding new ways—and new reasons—to be read.