Several practitioners of literature may want to add a polite footnote to the discourse around the genre of autofiction following the Nobel to French author Annie Ernaux. Most fiction carries an element of autobiography, whereas an autobiography may hardly be devoid of a fictionalised narrative. A text that attempts to unveil a fragment about the writer’s life often, deliberately or inadvertently, conceals another crucial bit.

When Ernaux’s novel The Years was shortlisted for the International Booker award a few years ago, the jury stated that she had lent the autobiography “a new form, at once subjective and impersonal, private and collective”. Ernaux, it might be added, follows a rich legacy of authors who chose the form of autobiographical novels. As they say, one goes to the novel to express the truth about one’s life and resorts to the memoir to record falsehood. Several great novelists have acknowledged their writings to be largely autofictions.

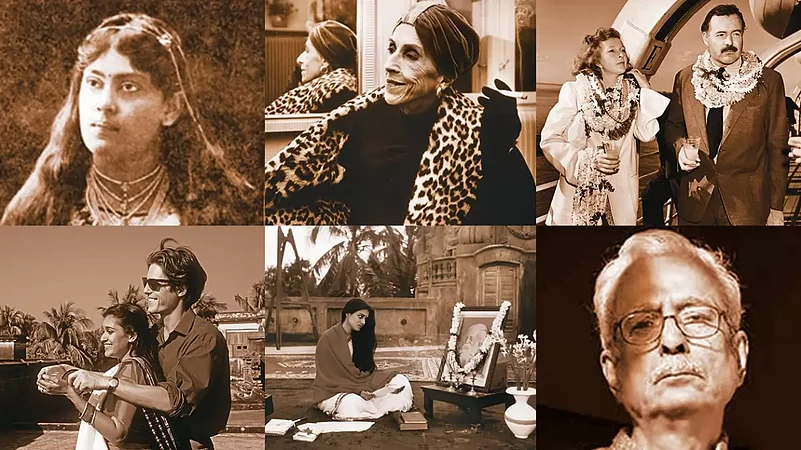

Many first-time visitors to the great Hindi novelist Vinod Kumar Shukla tend to believe that he himself is the protagonist of one of his works. I was no exception when I first met him in September 2011 at his Raipur home. As my bond with him deepened over the years, I hesitatingly shared my observation. He smiled and narrated an incident. Mani Kaul once made a movie on Shukla’s first novel Naukar Ki Kameez (The Servant’s Shirt). Upon meeting Shukla, he was convinced that the novel’s naïve protagonist Santu Babu was none other than Shukla and Santu’s wife was Shukla’s wife, Sudha.

The larger question about the form of autofiction lies elsewhere, a question that unravels the politics of the writer and the written text. What is the authenticity of the life mentioned in the novel, especially lives other than that of the author? It is widely known that A Farewell to Arms reflected Ernest Hemingway’s personal experiences in WWI and his love affair with a nurse. Let us turn to a testimony about another of his novels. Six years after Martha Gellhorn had been separated from Hemingway, she chanced upon her ex-husband’s new novel, Across the River and Into the Trees. A lot of water had passed under several bridges since they met last, yet Martha, among the most eminent war correspondents of the century gone by, was deeply hurt to find a cruel and uncharitable caricature of herself in the novel. “I weep for the eight years I spent, almost eight (light dawned a little earlier) worshipping his image with him, and I weep for whatever else I was cheated of due to that time-serving, and I weep for whatever that is permanently lost because I shall never, really, trust a man again,” she wrote to a friend.

Her hurt was genuine. Gellhorn’s biographer, Carl Rollyson, later informed us that Hemingway had admitted to an author friend Buck Lanham that in the novel, he had given it to “Miss M. in two paragraphs and pretty well for keeps. Don’t think she will be able to sleep good even with her glorious war record when she reads it.”

But while Gellhorn merely expressed her displeasure to a friend, another woman on another continent chose a different response to such a description in a similar work of autofiction. The Romanian author, Mircea Eliade, arrived in Bengal in the 1920s and stayed for several years. During his stay he came in touch with Rabindranath Tagore’s young protégé Maitreyi Devi and later published an autobiographical novel La Nuit Bengali (Bengal Nights, 1933), which claimed an intimate relationship with her. When Devi read the novel decades later, she was upset upon finding a distorted version of her life. She responded by writing another autobiographical novel It Does Not Die, published in 1976, and refuted his claims.

While the above are instances of fiction, let us come back to autobiography, a genre that supposedly deals only with truth, and nothing but the truth. To gauge the self-concealment inherent in autobiographies, one need not go beyond a telling episode in the life of one of the most transparent personalities of the last few centuries. During his Lahore visit in October 1919, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi happened to stay with Rabindranath Tagore’s niece, Saraladevi Chaudhurani, a singer and writer.

By then, Gandhi’s vow of celibacy was in its 13th year, but he immediately found himself enchanted by the talented woman. He was in Lahore again soon and wrote to his nephew, Maganlal, “Saraladevi has been showering her love on me in every possible way.” She began to feature prominently in Young India. They exchanged letters. “You still continue to haunt me even in my sleep,” Gandhi wrote to her. The bond, Gandhi’s biographer, Ramachandra Guha, notes, “came very close to” be “consummated sexually” until an anxious C. Rajagopalachari convinced Gandhi to withdraw as it would bring him “unspeakable shame and death”.

How does the episode appear in Gandhi’s famous autobiography, which mentions his various deviations, confessions and vivid details of his marital life? The man who laid bare his life to public scrutiny, who strove to live each moment in search of truth, concealed the entire episode about a woman he had once called his ‘spiritual wife’.

The world of letters abounds with such instances. Published memoirs and personal journals often record not what happened but what the author wants us to believe in. It may not be false, not always with the intention to deceive the reader, but it is often a partial and subjective evaluation of one’s life, riddled with the possibility of self-deception.

Leo Tolstoy and his wife Sophia kept two diaries each. One was a private document to record their innermost truths and another to delude or deceive their spouse—should they ever snoop on each other. A.K. Ramanujan was acutely aware of the threats a diary carries. His diary of October 5, 1980, candidly records an exchange with his wife, Molly Daniels. “Molly said she’d read much of my diary (don’t know when) and checked against what I said to her and found me a liar. Curious situation: Should one write a diary to suit a possible snooper, a reader over your shoulder?... I’m going to contrive to write what I think and feel.”

In other words, even if you write a diary for personal consumption and not with the intention to ever get it published, you may not record the truth if you are apprehensive of it ever being discovered by someone else. Since such anxieties often always remain, the most intimate form of a diary could also be the most treacherous genre, an attempt to deceive a future snooper. What one reveals may carry layers of what one has carefully concealed. In the era of social media, it has become easier to detect self-deception. Most diary snippets on social media posts instantly betray an inherent fakery and pompousness.

Precisely, therefore, the assertions of one’s writing, autofiction or plain autobiography will always face scrutiny by the subject of the text. Toni Morrison unravelled an incisive instance about racism, a sentiment that seeps into the works of even highly sensitive writers as their alleged superiority intervenes to guide their language. Morrison dissects an episode in Isak Dinesen’s autobiography Out of Africa. Dinesen is leaving Kenya after nearly two decades. Local African women have surrounded their patron-employer to bid her farewell. One woman breaks down, tears streaming down her face. Dinesen compares her with a giraffe, her unimpeded tears with a urinating cow.

Morrison launches a blistering assault. “The description of Dinesen’s African woman is instructive. The sticks on her head make Dinesen think of a ‘prehistoric animal’… The woman is like a giraffe in a herd, speechless, unknowable,” Morrison writes, “her tears are like a cow voiding its urine in public”. “In these passages, beautiful ‘aesthetic’ language serves to undermine the terms: the native, the foreigner, home, homelessness in a wash of pre-emptive images that legitimate and obscure their racist assumptions while providing protective cover from a possibly more damaging insight,” she writes.

In the end, I might turn the gaze inward. I am a prolific diary writer and record even the most unpleasant chapters of my life. I have also published several of my diaries. One of my books, The Death Script, borrows heavily from my diaries, recording my failures and confessions. Can I assert that my diaries contain each moment of my life? No. I could not muster courage to register several episodes in my diaries and the published ones are only a fraction of what I actually wrote. A chapter of my book ends with a confession: “One day, a Gond girl will read these pages, view me with suspicion, question my gaze, and reject every one of my words.”

Bringing real people to the centre of a literary text makes it a political enterprise, the politics of human relations, to be precise. A work of art that lays claim to real people or incidents may instantly generate interest, but it also enters a zone that is political first and aesthetic later— and hence demands a different scrutiny.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Between Memory and Desire")