Vulnerability in showbiz is still seen as either performative, unbelievable, or worse, unmanly.

For every star who comes forward, there are others who cannot or will not.

For mental health to be destigmatised in the glamour industry, we need to move beyond voyeurism and towards empathy.

Trigger Warning: This story contains mentions of suicide. Reader discretion is advised. If you or someone you know is struggling, please contact these numbers. | Helpline: iCall (9152987821) or AASRA (+91-22-27546669)— Available 24/7

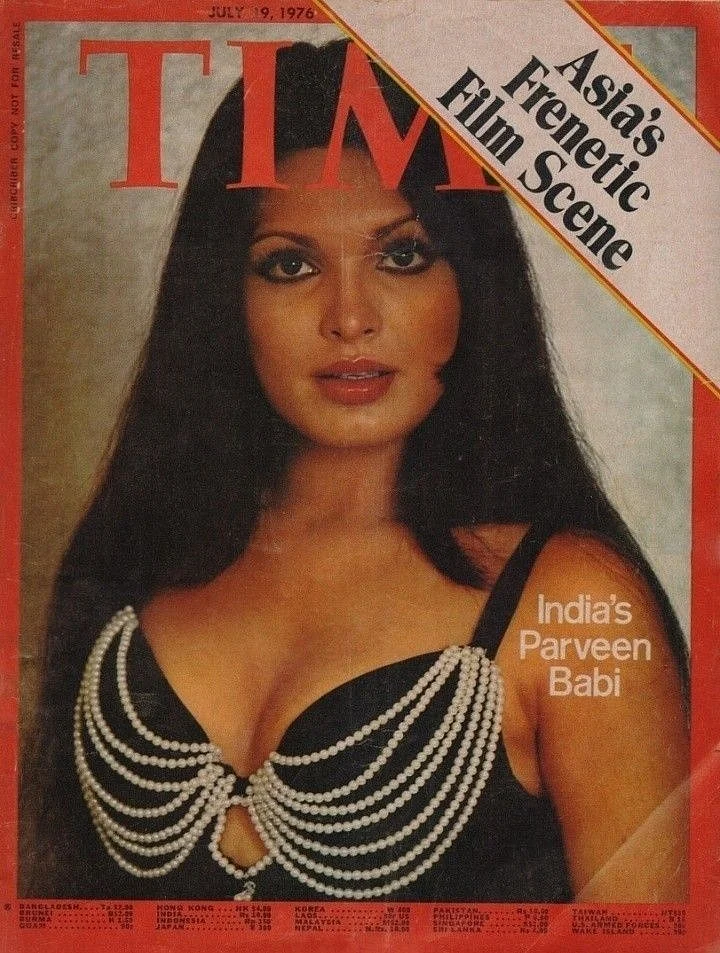

Charming, effervescent, and full of life on screen, Parveen Babi hardly came across as a figure who would eventually symbolise ostracism from India’s biggest film industry. She was the first Bollywood star on the TIME cover, after all. But hers became one of the earliest cautionary tales of Bollywood. “Her biggest fear was that if people got to know about her mental instability in the industry, they won’t give her work,” actor Kabir Bedi revealed in a recent interview about the 1970s and 80s icon, who became synonymous with schizophrenia in her later life.

There was never any public confirmation of a formal, clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia for Babi. There was never any verified documentation shared with the public—only the anecdotes shared by the men she dated, which included Mahesh Bhatt and Bedi. However, in her 1984 essay—The Confessions of Parveen Babi, published in The Illustrated Weekly of India—where Babi announced her retirement from Bollywood, she vividly wrote: “I lost trust in everybody and everything around me." Even the water seemed poisoned and the food felt suspicious to her, she wrote in the essay. Her confessions seemed to indicate her paranoid frame of mind.

Whether she had a medical condition or she was driven to her maladies by circumstances, Babi’s fears were tragically prescient. Shunned and dismissed, she exemplified how Bollywood—and our society at large—treats women battling mental illness.

A turning point at the intersection of Indian pop culture and mental health awareness appeared suddenly in March 2015. Deepika Padukone had opened up about her struggles with depression in an interview with Barkha Dutt.

By sharing her story, sitting in a panel alongside a counsellor and a doctor (and her mother), Padukone not only lent sensitivity and credibility to her experience but also grounded it in medical legitimacy. This moment signalled a shift.

Mental health struggles can emerge in the aftermath of traumatic events like grief, loss, and even burnout. But sometimes, there are no clear triggers, which is what happened to Padukone, who credited her mother with recognising the signs right away. “It just happened out of the blue,” Padukone would reiterate at later interviews. She confessed being suicidal at times, yet not comprehending what was happening to her, “I was on a career high. Everything was going well. So, there was no reason…”.

The way Padukone spoke about her depression became more than just a confession—it was a quiet act of public re-education. But for all her efforts and openness, we have only come so far in seeing stardom through the lens of humanity. In a country where going to therapy or admitting issues is still considered taboo, this is expected.

The Pathologisation of Femininity

Before Padukone, the most prominent face of mental health struggles was Babi. She was written off by the industry and the press as “crazy”, shortly after the discourse around her paranoid schizophrenia started floating in the media. Despite being such a big star, Babi lived her later years in relative seclusion.

When she accused powerful people, including Amitabh Bachchan and Bill Clinton, of conspiring against her, the press swiftly derided her. On July 14, 2002, she filed an affidavit—which she wrote all by herself with utmost clarity as per Karishma Upadhyay’s memoir Parveen Babi: A Life (2020)—claiming she had evidence linking Sanjay Dutt to the 1993 Mumbai blasts. A month later, she alleged that the CBI was conspiring to acquit him. The claims led nowhere as per Upadhyay’s novel.

Rather than offering empathy or nuance, the industry and the public mocked her suffering. A similar dynamic seems to be unfolding with Tanushree Dutta—one of the first actors to spark India’s #MeToo movement by accusing Nana Patekar of harassment—who is now increasingly portrayed as unstable, rather than heard.

The psychiatric condition Babi battled was overshadowed by misogynistic tropes—of the hysterical woman, the fallen diva. The tragedy of her life wasn’t just the illness, it was the culture that refused to see her illness as real, reducing it instead to scandal.

The Masculinity Trap

More than thirty years later, when Padukone decided to speak openly about her depression, one might have expected a more evolved public response. And while she did receive support, she was also met with dismissiveness. Salman Khan famously remarked that he didn’t “have the luxury” to be depressed. The insinuation was that depression was a bourgeois affliction—something idle, rich women had time for, not real men with real responsibilities.

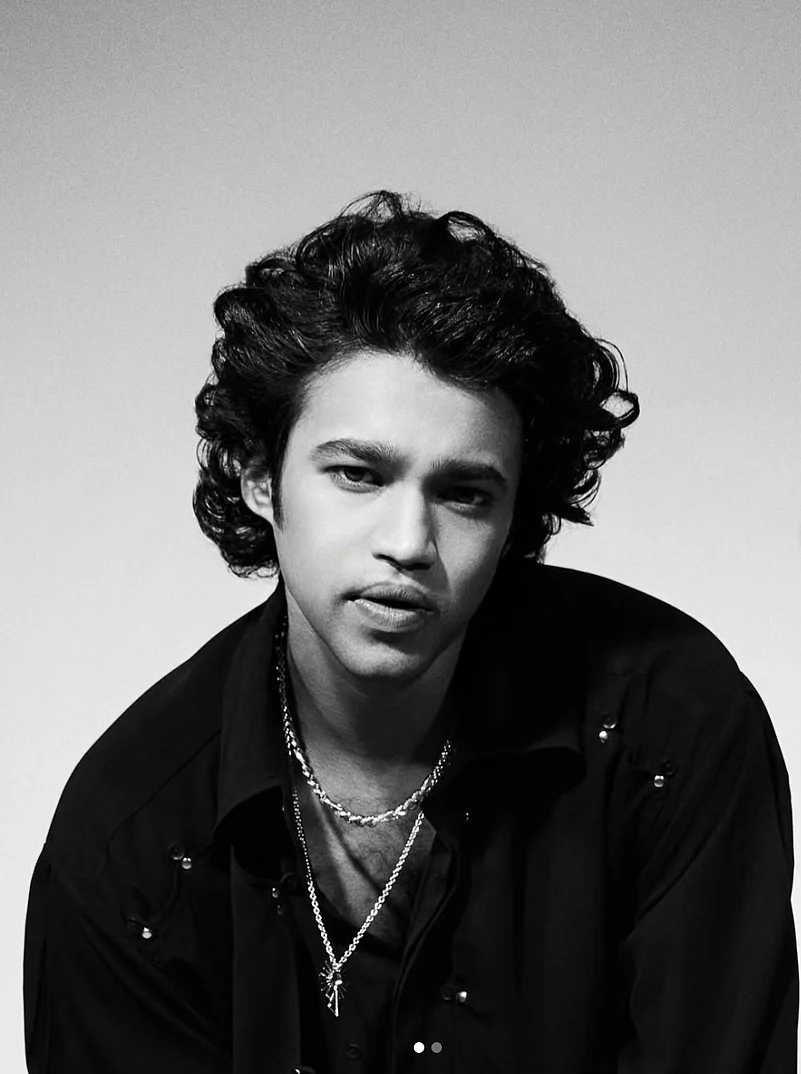

This gendered framing of mental health persists even now. When Irrfan Khan’s son Babil shared emotional, confessional posts on social media which showed clear signs of mental strain, he was accused of attention-seeking. Vulnerability in cut-throat industries like the media and entertainment is seen as either performative, unbelievable, or worse, unmanly.

This echoes the reaction to Sushant Singh Rajput’s tragic death by suicide in 2020. The possibility of a mental health crisis was entirely eclipsed by conspiracy. Rather than confront the uncomfortable reality of systemic industry pressures, much of the public and media veered into conspiratorial territory. Murder theories, political scapegoating, nepotism debates, and media trials filled the vacuum. India simply could not accept that an intelligent, beloved, accomplished young man could have taken his own life.

This refusal to engage with the possibility of Rajput’s mental health revealed something deeply telling about Indian society’s relationship with masculinity. In India, men are expected to be stoic, emotionally distant, and largely in denial of their afflictions. Even now, Rajput’s death is discussed as a mystery, not a mental health tragedy that could have been caused by lockdown loneliness, professional losses, or even bullying.

On the other end of the spectrum, women in the public eye are allowed, even expected, to feel—but even they must remain within limits. If Padukone cries while talking about her mental health, then that is seen as “excessive”, if you go by the innumerable Bollywood threads found on social media pages and subreddits. While women may have more cultural permission to emote, their disclosures are still filtered through condescension. Nevertheless, it is important that they continue to speak up.

This is why Alia Bhatt’s 2024 interview—in which she revealed being “clinically diagnosed with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) and anxiety” and struggling with it—felt like another pivotal moment. A mainstream celebrity disclosing their neurodivergence is a big deal. But some were still inclined to mock her—as though mental health diagnoses are fashionable affectations and she was simply jumping on the bandwagon.

This was the pattern seen with Anushka Sharma, Manisha Koirala, and Ileana D’Cruz, all of whom have spoken about anxiety and depression. Their conditions are seen through a cultural lens that pathologises female emotion as a flair for seeking drama or as a flaw to be expected. Symptomatic of this school of thought and in a gross violation of her privacy, Ranbir Kapoor made fun of Sharma in an interview and divulged that she has been on medication for anxiety without her consent.

The Myth of the Tragic Muse

This discomfort with female emotion has historical roots. Meena Kumari’s life and image are proof. Long dubbed the “tragedy queen,” her on-screen roles mirrored her tumultuous personal life, particularly her alcoholism, loneliness, and heartbreaks. She became the tragic heroine off-screen too. But it wasn’t always empathy that led us to seeing her through this unilateral lens of perpetual sadness. It was myth-making.

The culture romanticised her pain without ever naming it as mental illness or addiction. Her alcoholism was seen as poetic, her desolation as beautiful. There was no vocabulary then—at least none that the media or the public was willing to engage with—to understand her experience as psychological suffering. Some of it was part self-mythologising and part external.

When asked about her likes and dislikes, Kumari famously said, “I like death,” as mentioned in a story from India Today. Her Urdu poetry, written under the pen name Naaz, was also filled with themes of loneliness and longing, offering a window into her inner world. Vinod Mehta’s 1972 biography on Kumari, drawing from interviews and magazine archives, painted a portrait of a woman deeply in pain.

Thus, she was turned into an icon of doomed womanhood much like Marilyn Monroe, who endured a similar fate at the hands of the Hollywood media. Her suffering was aestheticised and turned to trauma porn over decades, rather than recognised as psychological distress.

Judgement and Spectacle

The cases of Rajput and Babil suggest that nothing much has changed over the years. While today’s public might be more literate in the language of anxiety, depression, trauma, and neurodivergence, our society’s deeper discomfiture with mental illness remains. There is a persistent desire to reframe it or render it invisible. And when that isn’t possible, it is either weaponised (as in the witch-hunt of Rhea Chakraborty) or dismissed (as in the mockery of Khan, Sharma, and Padukone’s candour).

What all this reveals is a deeper cultural malaise. We are more comfortable with celebrities when they conform to their roles. They are our heroes and style icons. They are our sanitised success stories.

Them showing up with their fragility threatens the roles assigned to them. It introduces a complexity we as a society were never taught to deal with. In a country where celebrities are deified and worshipped, we do not want to know that they live with the same fears, melancholia, and biochemical imbalances as the rest of us. For every star who comes forward, there are others who cannot or will not (which is perfectly valid). The risks are still high.

If Kumari were alive today, would we be able to see her alcoholism as a coping mechanism for untreated depression? If Babi were to speak out now, would we finally hear her, instead of laughing her off as a circus act? The answer, painfully, is no.

But the ripple effects of celebrities speaking sensitively about their struggles are palpable. BBC journalist Elena Bailey enquired on a Reddit thread a few years ago if and how celebrity revelations helped people. Several noted that it helped them be kinder to themselves and destigmatise the “shame and embarrassment” attached with their diagnoses.

Beyond Bollywood

Several actors from regional industries have also begun breaking the silence around mental health. Bengali actor Parno Mittra has spoken openly about experiencing suicidal thoughts and persistent depression, urging people to take mental illness seriously beyond social media trends.

In the South, Samantha Ruth Prabhu has credited therapy and peer support for helping her navigate personal turmoil. She framed mental illness as treatable and comparable to physical health issues. Tamil actor Vishnu Vishal revealed his struggles with depression, stress eating, and alcohol dependence after a series of injuries and personal debacles. Shruti Haasan has candidly discussed the emotional and hormonal upheavals she faced, emphasising body acceptance and mental well-being.

Most strikingly, Malayalam actor Fahadh Faasil recently disclosed being diagnosed with ADHD at the age of 41—one of the few public acknowledgements of adult neurodivergence in Indian celebrity culture in addition to Bhatt’s.

In an attention economy, it is understandable that these celebrity confessionals are looked at with suspicion. One often wonders about their ulterior motives. But there is hope to be found because regardless of motivation and intention, this provides a new discourse for those who are tuning in and starving for some conversation. More celebrities speaking, not in riddles or euphemisms, but in the language of the people is welcome in this scenario. These revelations then, themselves become political acts, in a culture that still stigmatises emotional complexity.

Of course, for this discourse to take root, we need to move beyond voyeurism and inch towards empathy. However, as public discourse seems to show, there are still miles to go before that happens.

Debiparna Chakraborty is a film, TV, and culture critic dissecting media at the intersection of gender, politics, and power