Summary of this article

BMC’s demolition of Marathi-medium schools under the guise of ‘dangerous buildings’ has triggered allegations of real-estate interests and manipulated audits.

Parents and activists say there is no transparency and dialogue between stakeholders by the BMC.

With no elected corporators for 3.5 years, citizens question how long key education decisions can continue without democratic accountability.

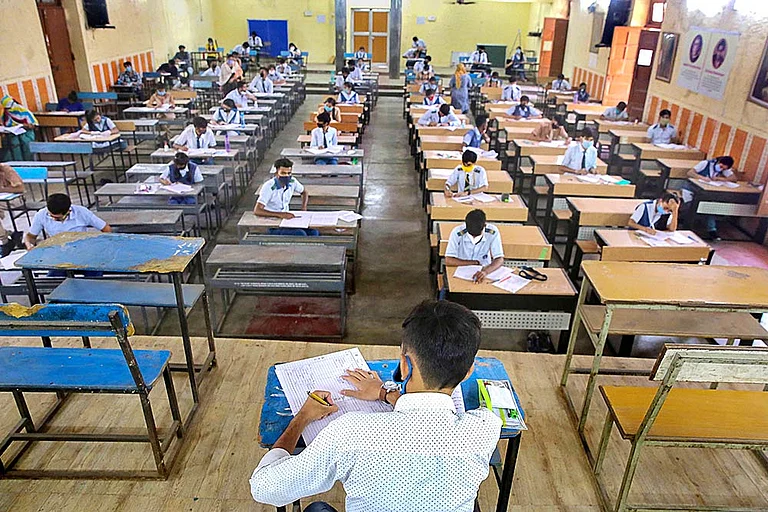

Aryaman, 11 (name changed), was studying in Class 5 at the New Mahim Municipal School in Mumbai. The school is now shut, and from August 2025, Aryaman and hundreds of students like him have been shifted to another municipal school. This new school is located far from the old one — on the first floor of a residential building in the Kapad Bazaar Road area in Mahim, functioning out of a few rooms.

The new school- where students are relocated, lacks a playground, proper drinking water facilities, and toilets with adequate water supply. Since moving here, Aryaman and his friends have almost forgotten what it feels like to play. This is the plight of students whose Mumbai municipal schools have been merged into other schools — under the pretext of building repairs.

Between 2013 and 2025, a total of 131 Marathi-medium schools have been shut down, according to various news reports.

The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) has begun efforts to demolish several Marathi-medium school buildings in the city, citing that they are ‘unsafe buildings’. The administration, using various justifications, has prepared structural audit reports leading to predetermined conclusions, and some buildings have already been razed on this basis, activists of Marathi Abhyas Kendra alleged. Notices have now been issued even to well-maintained buildings that could last many more years with the proper repairs.

New Mahim School is one such institution — kept shut by the BMC on the grounds of required repairs. The school had been fully renovated in 2015. Now, within just ten years, the corporation has declared the building unsafe. This has prompted several citizens to question the quality of the previous repair work. Meanwhile, the Marathi Abhyas Kendra has demanded strict legal action against contractors who allegedly carried out poor-quality repairs, putting students’ lives at risk.

Around three to four years ago, the municipal school on Mori Road in Mahim was demolished. Today, the site remains a fenced-off empty plot. No new school has been built there. In the past two years, a 21-storey tower named Mahalaxmi Residency has come up right opposite this vacant land, where a one-BHK flat costs nearly Rs. 2 crore.

Local residents of Mahim told Outlook that such a centrally located, prime plot lying unused is likely attracting interest from a minister or a developer connected to those in power. When we spoke to people at the nearby Dighi Tank public garden, many of them also expressed concern over the municipal corporation’s push to shut down schools.

“We have been protesting for years to save Mumbai’s municipal Marathi schools. But now, the corporation has started bulldozing these schools, Land Mafias are eyeing such prime lands owned by schools. The BMC is destroying the education of poor children, and soon these plots will be handed over to real estate developers. Many schools only needed minor repairs and could have continued functioning. Instead, the BMC conducts structural audits, gets the kind of reports it wants, and then demolishes the schools,” Dr. Deepak Pawar of the Marathi Abhyas Kendra told Outlook.

Activists from the Marathi Abhyas Kendra said they have written letters to BMC Commissioner/Administrator Bhushan Gagrani regarding the condition of municipal schools in Mumbai, including the one on Mori Road in Mahim and the school in the New Mahim complex. However, they have not received any satisfactory response from the administration.

The BMC informed citizens that “the reconstruction work of the Mahim’s Mori Road school building will start soon, The tender process will be completed, and a work order will be issued by the end of November 2025.”

However, activists working in the education sector and citizens have questioned why the BMC is planning to demolish yet another school on Chhotani Road when the Mori Road school has already remained shut for three-and-a-half years and even the basic tender process for its reconstruction has not been completed.

Lack of transparency by the BMC

Citizens have accused the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) of a serious lack of transparency. Activists associated with the Marathi Abhyas Kendra have repeatedly engaged with the administration, questioning the ongoing policy of shutting down municipal schools. One of their key demands has been the public disclosure of the structural audit reports that the BMC relies on to declare school buildings “unsafe” and shut them down. However, the civic body has neither uploaded these reports on its website nor released them in the public domain through press conferences or other means of communications.

In Mahim’s Kapad Bazaar area, a two-acre parcel of land originally reserved for a municipal school and playground has seen the construction of two skyscrapers—48 and 25 storeys high—over the past three years. Only 11 rooms on the first floor of one tower have been allotted for a school, while the playground has been completely wiped out.

A similar pattern is visible in Lower Parel. The BMC’s Marathi pre-primary school earlier operated from a dedicated space on the premises of the historic Manaji Rajuji Chawl on Babaji Jamsandekar Road. After redevelopment, however, a 35-storey tower has come up, and the school has been pushed into just two or three rooms carved out in the parking area, leaving students with no proper infrastructure.

“The systematic demolition of school buildings is not just about ‘safety concerns’ as the municipality claims. It is part of a larger nexus between land mafias eyeing valuable educational plots and the municipal administration working at their behest. Saving Marathi-medium schools is therefore not merely an education issue—it is a broader fight for Marathi identity and the very ethos of Maharashtra,” says Dr. Pawar of Marathi Abhyas Kendra.

No dialogue with stakeholders by the BMC on relocation of students

Despite multiple emails and formal letters sent by the Marathi Abhyas Kendra seeking a meeting with the Municipal Commissioner to discuss issues such as school closures, mergers, student relocation, and the demolition of old buildings without constructing new ones, the BMC did not grant them an appointment. Instead, the administration responded with a brief written note stating its position. On the crucial matter of shifting students, the BMC has not held any discussions with parents, parent representatives, Right to Education activists, civic groups, or local political and social workers. Nor has it explained its policy to any stakeholder directly.

The municipal administration claims that when unsafe school buildings are shut down, students are shifted to nearby municipal schools without academic disruption. However, citizens demanded that the BMC publish a student-wise and school-wise list of relocated students in nearby schools. This information has still not been made public on the BMC website—or anywhere else—raising further concerns about transparency.

Parents say that without issuing any written communication or even putting up a public notice at the school, School Teachers simply informed them verbally that their children would now have to attend far-off municipal schools in Sion, Worli, Kapad Bazar and the Worli Fishing Colony.

Marathi Abhyas Kendra organised multiple protests in Mumbai to highlight these issues. Its recent protest took place on November 9, outside the Mahim municipality School where several parents from Mahim and Dharavi joined in.

“My two children studied at the municipal school on Chhotani Road in Mahim. About three months ago, we were told that the building needed repairs, and that if the ceiling collapsed someday it would endanger students’ lives. So all children would be shifted to the Kapad Bazar school,” said Shagir Ahmed from Dharavi, speaking to Outlook. “Now my kids walk nearly 45 minutes every day just to reach school. We can’t afford bus or taxi fares — we live hand-to-mouth.” Ahmed added.

According to the Right to Education Act, 2009, it is the government’s responsibility to ensure that schools are available within 1 km for primary education and within 3 km for secondary education from a child’s residence.

Outlook contacted the BMC’s Commissioner(Administrator who governs in the absence of elected BMC) Bhushan Gagrani to understand the BMC’s role and its way forward to fulfill demands of citizens regarding BMC schools; we didn’t get his response.

Governance Without an Elected Mandate

For issues related to the repairing work and demolition of Mumbai Municipal Corporation schools, as well as the relocation of students to nearby schools, there are no elected representatives—no corporators—to contribute to policy decisions, or challenge it. Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) elections have not been held for the last three and a half years. In this situation, BMC Administrator Bhushan Gagrani has been taking all decisions. "How long will an administrator continue to make decisions that directly impact people’s lives without an elected mandate?" citizens are raising this question.