On a May afternoon in 2009, a young man in his early 30s— sporting a moustache and sharing uncanny similarities with his father Dishom Guru Shibu Soren—suddenly got to know that it was his ‘turn’. Soren’s paternal house in Ramgarh, around 50 km from Jharkhand’s capital Ranchi, was yet to get over the death of their elder son Durga. But the brother didn’t even have time to mourn. He had to take the mantle. He knew ‘Guruji needed help’.

The year 2009 changed the political fate of the Soren family and by consequence, that of the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (JMM). A new leader was born in Hemant Soren who not only spoke of the rights of the marginalised but also emphasised Adivasi unity by evocating the Sarna dharma—an ideological resistance to the efforts of the Right Wing to incorporate Adivasis within the broader Hindu fold.

In the last 15 years—from the emergence of Soren as a ‘humble’ Adivasi leader to his recent arrest for his alleged involvement in a land scam—the JMM has witnessed many ups and downs. Sometimes, it was found aligning politically with Right Wing parties like the BJP—with whom they have ideologically contested historically—and sometimes it hobnobbed with traditional allies like the Congress and the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD). However, as the recent social media post of Kalpana Soren, the JMM’s new face and Soren’s wife, mentions, the core ideology of the party has remained the same. It still stands for the “poor, deprived and exploited, including tribals, Dalits, backward classes and minorities,” writes Soren.

To talk about the ideology, one must, nevertheless, look into the long journey of the party spanning more than 50 years. The history that predates Durga, Hemant, Kalpana, Sita, Besant, and other Sorens lies in the formation of a strong political ideology that survived consecutive storms and the unwavering spirit of a Santhal leader—Shibu Soren—who dared to speak against the moneylenders in the 1970s, and held the dikus (outsiders) culpable for the fate of Jharkhandis.

***

It was the winter of 1957. A 15-year-old Shibu was waiting for his father in the school hostel at Gola block of then undivided Hazaribagh district. However, his wait became never-ending. His father Sobaran Soren, a school teacher and a social activist—who had been fighting against the moneylenders— was murdered on his way to Gola. Though Shibu couldn’t meet his father ever again, he carried his ideology with the promise that he would end the exploitation by moneylenders in the Santhal region.

Within years, a young Shibu launched the ‘Dhan Kato’ (reap paddy) movement which resisted moneylenders looting their land. This agitation soon became popular in other parts of the Chhotanagpur plateau and Shibu became a household name.

As the movement garnered strength, along with the ongoing political mobilisation of industrial workers—demanding the representation of Adivasis under the leadership of A K Roy—the political trajectory of southern Bihar was taking a crucial turn. On the other hand, the Kudmi Mahatos of the Chhotanagpur region, who had been demanding to be clubbed with their Kudmi brothers (in terms of identity) since the 1920s in Bihar, formed the Shivaji Samaj. The Samaj run by Vinod Behari Mahato also wanted to join the fight with others.

In 1972, Soren, Mahato and Roy together addressed a meeting of more than a lakh people at Dumri. “Seeing the crowd, they decided to form a platform together to take the cause of Jharkhand forward,” says Qari Barkat Ali, a JMM veteran who has been a central committee member of the party for almost 20 years. During this time, the Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha had already been formed and Roy suggested naming it the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha and in the following year, the organisation was formed, adds Ali.

However, Abha Xalxo, a Jharkhand-based researcher, mentions in her works that neither did Roy merge his Marxist Co-ordination Committee (MCOR) with the JMM nor did Mahato dissolve its identity. “These leaders coordinated their activities but could not forge a united front. The result was that each one functioned autonomously,” she writes. But the socialist ideology, as influenced by Roy, was a part of the JMM in the early days.

The journey of the JMM that started with the socialist struggle for Land soon turned out to be a fight for a separate state and rights to Jal, Jungle and Jameen.

The major objectives as noted in the preliminary constitution of the JMM—apart from promising a separate state—also contained two significant points: First, “to end the exploitation of tribals by non-tribals”, and second, “to bring about a radical change in the Jharkhand society in order to make it free from backwardness, inequality, ignorance and poverty”.

But the major obstacles in the path of these objectives were liquor consumption and the lack of education. Xalxo notes: “In spite of engaging themselves in forcible harvesting of paddy from their alienated lands, the Santhals were demoralised. They would consume alcohol to escape from the ugly reality.”

So, the JMM took a turn towards social reforms and started four dedicated programmes—the anti-liquor campaign, literacy programmes for children, grain banks in rural areas, and direct-action campaigns to ‘recover the alienated lands in the region’. While tracking the journey of the JMM, authors Sanjay Kumar and Praveen Rai write: “The JMM and the MCOR formed the Jharkhand Alliance between workers and peasants based on a leftist ideology by redefining ‘Jharkhandi’ as anyone who worked and ‘diku’ as anyone who exploited others”.

Though the party did not think of contesting elections in the initial years, by 1980, it realised that it needed to have representation in the Lok Sabha and the Assembly, says Ali. In 1980, the JMM fought its first election with its symbol of arrow and bow and Shibu Soren became an MP from Dumka.

By this time, the main focus of the party was to achieve separate statehood for Jharkhand and to relieve Jharkhandis from the exploitation of outsiders/dikus. So, the political considerations and ideological alliances were also formed accordingly. Supriyo Bhattacharya, the general secretary of the party, says: “In 1995, we told the Bihar government that we would support Lalu ji only if the Bihar Assembly passes a resolution for a separate state. After that, in 1999, we passed the Bihar Reorganisation Bill and sent it to the Central Government. When Guru ji’s delegation went to then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, he agreed to support this bill.” But a section of the BJP insisted on naming the state Vananchal and the party didn’t accept it, adds Bhattacharya.

During this time—in 1998—Shibu Soren held a press conference flanked by Lalu Prasad Yadav and Mulayam Singh Yadav and joined the Rashtriya Loktantra Morcha. Launching a scathing attack against the BJP, Soren said: “They have spread the fight over mandir and masjid across the country. They are spreading hate.” Echoing the words of two Yadav leaders, the Adivasi icon also called for the broader unity of Adivasi, Muslims, Dalits, OBCs and other marginalised communities. “Why are they calling it Vananchal? We are Jharkhandis and no other name is accepted to us,” Soren fumed.

***

In 2000, Jharkhand ultimately became a state, even though the demands of including districts from West Bengal and Odisha were not met. But the popularity of the JMM did not translate into votes. In the 2000 Bihar Assembly Elections, prior to the separation of the state, the JMM won only 12 seats out of the 85 it contested. With a 3.5 per cent vote share in undivided Bihar, the party couldn’t have much impact. As it was decided that the party that won the 2000 Bihar Assembly Elections would rule Jharkhand in the first term, the BJP’s Babulal Marandi became the Chief Minister of the newly-formed state.

In the 2004 Lok Sabha Elections, the JMM with its alliance partners the CPI, the RJD and the Congress performed pretty well, winning 13 out of 14 seats. However, the very next year, in the Assembly Elections, the same alliance could only get 26 out of 81—15 less than the majority mark. Still, Shibu Soren was the popular choice for the CM. “But his government could not sustain for more than 12 days as he failed to prove his majority,” says a political analyst.

Again, Jharkhand got a government backed by the BJP and run by an independent, Madhu Koda. While talking about the diminishing popularity of the JMM in the 2005 Assembly Elections, Kumar and Rai note that apart from an upsurge in voters’ participation that led to fragmentation in voting, a ‘lack of unity and cohesion’ among the secular forces became one of the major reasons for the debacle.

As the alliance of secular forces failed to clinch victories in consecutive elections and an ‘ambitious’ Soren was getting ‘desperate’, Guru ji took the support of the BJP to form a government in 2009. Though the government sustained only for 153 days, followed by another BJP-led government where Soren’s younger son Hemant became a deputy—that survived for 2.5 years—it instilled some political discontent within the party. Senior JMM leader and MLA Lobin Hembram, who was brought into the party in the 1980s by Guru ji himself, says: “We never supported it. We even went to Delhi to form the government with the Congress. But Hemant became the deputy CM and supported Arjun Munda.”

However, their political bonhomie was short. Insisting on the implementation of the domicile policy that was supposed to define Jharkhandis and prioritise them in government jobs and education, Hemant left the Munda government, leading to its fall. “But the same Soren government, now with the support of the Congress and the RJD, couldn’t implement the domicile policy,” laments Hembram. Notably, Hemant never repeated the ‘mistake’ of taking support from the BJP again, says senior journalist Faisal Anurag. While referring to the arrest of Hemant, he said: “If he had broken the alliance with the Congress four months ago and accepted the CM-ship of the BJP on the condition of making some of his leaders ministers, he would not have been in jail. He is paying the price.”

Following a brief period of presidential rule—the third in a row since the state came to existence—Hemant Soren, for the first time, became the CM of the state with the support of secular parties. However, in 2014, the JMM went alone and faced an electoral debacle—presumably due to the persisting ‘Modi wave’—and the BJP formed the government under the leadership of the first non-Adivasi CM of the state—Raghubar Das.

In these first 14 years, the state witnessed so much political instability that not a single government could complete a full term and the objective of working for the people’s rights over Jal, Jungle and Jameen remained unfulfilled. The JMM leadership attributes this to the politics of the BJP. “Everyone has seen the kind of political conditions and instability that existed in the state. How the BJP played the politics over religion, sect, caste, outsider, insider, tribal origin is known to all. Amidst such instability, the original objective was lost,” says Bhattacharya, the JMM general secretary.

***

During Das’s tenure, the efforts of the BJP government to amend the CNT and SPT Acts backfired and consolidated Adivasis in favour of the JMM, says Geetashree Oraon, the former education minister of Jharkhand. Though the then governor of the state, Draupadi Murmu, declined to sign the bill that allegedly diluted the land protection acts and sent it back to the government facing huge protests, the JMM already gained ground. “The consolidation of the Adivasis against the Das government and the promises of the JMM to continue their fights for Jal, Jungle, Jameen helped them to gain a majority in 2019,” says Hembram.

This was the first time the JMM got 26 out of the 28 Adivasi seats. Though scholars point out that the JMM’s major vote bank has been the Santhals, this time the Adivasis unanimously voted for them. “Actually, Adivasis vote for those parties whom they find to be credible. The promises of the JMM worked in 2019 as they thought that the promises would be kept,” says Chamra Linda, an MLA and a senior leader of the JMM.

Since 2019, Hemant repeatedly tried to woo Adivasi constituencies and came up with the Sarna code bill, the domicile policy and the 27 per cent reservation for the OBCs. Was it an effort to accommodate the non-Adivasis as well? “Till 2000, the OBC reservation was 27 per cent, but in 2001, Babulal Marandi abolished it and reduced it to 14 per cent. We have only corrected it and the JMM has a policy of taking everyone from the beginning,” says Bhattacharya.

Hemant Soren’s assertion of the Adivasi identity through the words, “They can’t tolerate Adivasis riding a BMW” resonated among the community. And it was reflected in the protests that hit the streets after he was arrested by the ED. The fight for Sarna identity—the recognition of a separate religion for the Adivasis—has become the trademark of the Soren government, says a senior journalist. Champai Soren, the current CM, while talking about the JMM’s Adivasi politics, says: “We are simply asking the central government to give us Sarna status. We want to unite Adivasis-Moolvasis across the state to fight against the divisive politics of the BJP.”

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

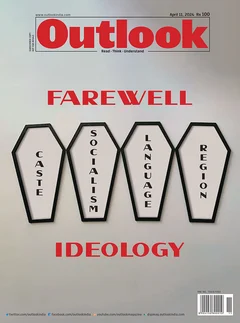

So, the journey of the JMM that started with the socialist struggle for land soon turned out to be a fight for a separate state and rights to Jal, Jungle and Jameen. Though in the first decade after the formation of the state, it took a rightist turn for some time with its coalition with the BJP, it gradually fell back on its secular allies and plied on identity politics. This turn—from the Left to the Right to the Centre—captures the overall journey of the JMM. However, the words of Kalpana Soren perhaps depict it the best: “The JMM was born from the coordination of socialism and leftist ideology” but is moving forward to incorporate all—the marginalised of the society.”

(This appeared in the print as 'Left, Right & Centre')