In the Indian context, talking about the phenomenon of identity politics in soft if not patronising language has become a part of shishtachar—a form of politically correct etiquette that seems to have been adopted as a safety blanket by ‘progressive’ political commentators. Such public practice of political etiquette tends to mean avoiding objectively critical, frank and, therefore, redemptively forward-looking evaluation of such politics. In fact, the scholars as well as commentators who cast their eye on identity politics end up becoming mere ‘observers’, defending the phenomenon less out of conviction or any radical commitment to emancipatory possibilities and more out of social obligation. The practice of shishtachar as public protocol, thus, mostly results in them offering mere rhetorical affirmation rather than any real critical evaluation of this genre of politics. This includes avoiding commenting on what could be termed as the deeply problematic directions in which the practitioners of identity politics may have sojourned all these years.

On methodological grounds, such an unconditionally affirmative assessment tends to approach identity politics on its own self-sufficient—indeed, self-serving—terms rather than in critical reference to mainstream politics. Such a skewed or ‘privileged’ frame of reference is prominently followed in particular regard to Dalit politics—politics that is treated as distinct and separate from the canonised ‘secular’ version of politics. This distinction is achieved by resort to a dual interpretative strategy that rests on its own perspectival split: between modern and late modern. This is an endless conundrum, but in either case identity politics embodying Dalithood in actual sense gets reduced to its particularity.

ALSO READ: Silver Jubilation

Through the first lens, this is done by using the grand narratives of a normative political order—such as secularism—as a standard of measuring the normative stamina of Dalit political orientation. This is often evident in the ‘secular’ concerns expressed by those who, for the right reasons, stand with those grand narratives. The holders and adherents of grand narratives suggest that Dalits are not yet ready to become modern, and this benign concern finds its expression in the lament about the growing communalisation of Dalits. Paradoxically, the lament suggests two opposite tendencies within Dalits. First, that communalisation is a pathological trait that has unmitigatingly inveigled Dalits into its regressive logic. On a more charitable note, it also assumes that resistance to communal politics is an innate quality naturally available within Dalits. Both assume a kind of natural proneness—structural compulsions are ruled out as a reasonable tool of understanding.

Linear expectations that Dalits should always be modern-secular, however, runs contrary to the scholarly ethic of late modernity which would like Dalits to resist communalism locally—as an outcome of the body and its location in a politicised space—rather than express their allegiance to secularism universally. This alternative standpoint situates Dalit politics within the framework of late modernity which seeks to privilege, if not celebrate, the assertion of identity and difference. From this point of view, social identity, particularly in the Indian context, has always been defined in terms of caste and tribe; and difference in terms of minority politics.

In this regard, we need to raise two sets of questions. First, what impact does mainstream and hence modern politics have on the tenor and tenacity of Dalit politics? Do Dalits have the cognitive faculty and moral need to craft their political response to certain universally desirable values such as egalitarianism and secularism? Is it structurally possible to fashion autonomous political carriers for their social assertion? Put differently, can identity politics remain separate from the political influence of dominant parties? And maintain its autonomy from the politics of the dominant? Second, what impact does an entanglement with mainstream politics have on the normative quality of the autonomous political existence of Dalits? What are the grounds on which the dignity of the political judgement to remain autonomous can be assured and protected? Let us explore possible explanations around this skein of issues.

The relationship that numerically dominant parties have established with Dalit politics has been instrumental at its best and patronising at its worst—it has been far from egalitarian, in terms of sharing equal worth. It has been instrumental in the sense that parties, whenever they were in dominant positions or were trying to acquire such positions, were motivated to use the electoral support of Dalit leaders. The intention is purely to consolidate the dominant power position. The feeling that ‘Dalits have been instrumentally used’ has been prevalent among common Dalits across all regions of India. Arguably, the sense of political subordination is felt more intensely in the particular context of Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra, whenever Dalit leaders went into formal or informal alliances with political parties with a dominant-caste social orientation. In the instrumental framework, the relationship between the dominant and subservient can be considered to be at its most useful when it has exchange value both for dominant parties and also Dalit individuals. Insofar as dominant castes take Dalit politics relatively a little more seriously on instrumental grounds, Dalits tend to benefit from such alliances at the individual level. Dalit votes, projected into a ‘votebank’, then serve as a common resource—Dalits use it to augment their personal interest while the dominant party uses it for consolidating its power. Both Dalit politicians and dominant party leaders benefit from such an exchange: a partly cynical tradeoff wherein Dalit leaders assure Dalit votes and dominant parties in return give the former some not-so-significant position of power. It is in this sense that for Dalit leaders the social is political and personal—a political bargain that serves personal interest rather than the collective aspirations of the community they claim to represent.

ALSO READ: Postcards From The Newsroom

Dalit accommodation into a politics of patronage controlled by the dominant party is at its worst on a normative ground, which makes patronage outrageous to the self-respect and dignity of the Dalit politician. The moral good of Dalits is thus put at stake here. In the worst cases, Dalit politicians do end up becoming a worn-out instrument for the dominant: an element undesirable but also unavoidable. Gradually, their exchange value also gets diminished to the point that the dominant party does not need to depend on Dalit support for nurturing or validating its power. Dalits in such a relationship prefer to live by the political courtesy of the dominant—put bluntly, they tend to compromise their self with servility and subordination. Expressions of such utter subordination can be found in the most recent attempts to project oneself as the loyal servant of dominant party leaders. In this regard, it is equally interesting to note that there is no moral disclaimer from dominant leaders to being accorded such a cultural, mythological elevation by any leader from the margins. Everyone loves appreciation, celebration from others. Why blame the Dalit alone for conferring it? That would be an insinuation—in itself a deeply morally objectionable category.

Political Billiards

The Dalit subordination to dominant political personalities in power relations can be explained by using the analogy of the stick used in the game of billiards. It is the one who holds the stick who decides the desired direction and destination of the ball, by manoeuvering it with the requisite pushes towards the chosen pocket. In the power game, it is the big players who decide which person should get the ticket and the berth. A person being picked by the powerholder, like a billiard ball, does not have his/her own dynamics to reach the desired destination, such as elected bodies at different levels of institutional democracy. More importantly, such a person, again like the billiard ball, does not have his/her own dynamic to act against the diktat of the stick—he/she has to follow that diktat. Dalits, like many non-Dalits, do not possess the powerful hand that holds the stick but for personal, subjective reasons choose to operate like the billiard ball. I am sure this is a rather unpleasant indictment of Dalit politics, but sometimes removing rough edges from the language of assessment does not serve any constructive purpose. Yes, this is a form of vulnerability, but it calls into question their commitment to the principle of autonomy.

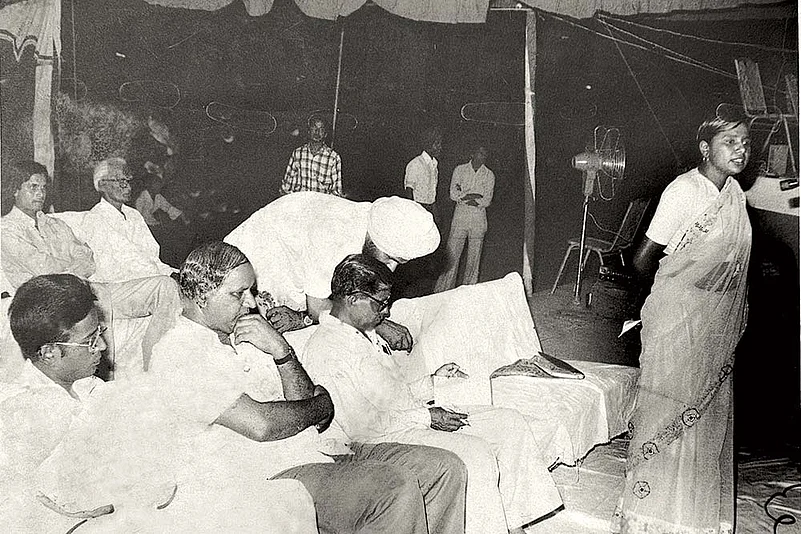

Mayawati, 1980

The predicament of Dalit and even minority politicians does suggest that it is a difficult passage for leaders from the margins to establish a moral claim for autonomous politics by genuinely and effectively standing against anti-democratic, anti-secular politics. The question we need to address is the following: where lies the normative essence of the claim to autonomy? In being able to take adamant independent decisions just because one has a sociological or religious hold over a social group? Or does the essence of autonomy lie in being careful in foreseeing the possibility of destructive consequences such decisions would produce? As we have seen in the recent elections, the decision to contest elections just to exercise the claim to autonomy has knowingly and unknowingly helped right-wing politics.

ALSO READ: At Swim, Two Birds Perched On Latticed Sites

At one level, in a liberal argument, it is possible to ask that if a group is trying to maintain its autonomy for the sake of achieving self-respect, why should one find it blameworthy? However, self-respect does not lie in assertion of autonomy alone; it lies in the moral capacity to detect the truth that necessarily flows as a consequence of that exercise of autonomy. If contesting elections separately is going to indirectly confer an advantage on a communal party, such a decision is certainly blameworthy. If such a group is in alliance with the combination of secular forces in the fray, that same claim to autonomy certainly acts in favour of truth—the truth of minimising the danger of right-wing outrage. In such a normative context, an electoral alliance would be praiseworthy as it would necessarily produce positive results—for social democracy in the case of Dalits, and for secularism in the case of minority aspirations.

In conclusion, it could be said that in Dalit politics what is discernable is both an inability and an unwillingness to make a dent in the larger politics. Paradoxically, at the rhetorical level, Dalit politics has been claiming that they are the followers of Babasaheb Ambedkar and hence have an auto-established claim over the universal ideas of justice, equality and dignity. But they have not been able to make these ideas universalisable or acceptable across social contexts. Packaging these ideas into slogans and selling them only to a specific social constituency is definitely self-serving. Without making universal ideas universalisable, and yet dreaming to become the most important person in Indian politics, would result only in oversimplification of the complex reality of caste—a reality that stands as the single-most important hurdle in the process of making ideas universalisable. Thus, a Dalit becoming the prime minister of India, unfortunately, is likely to remain wishful thinking: a thinking that had acquired currency in the context of the US electing Obama as President. Given this political impossibility, Dalits need to reinvent their politics—aiming it at making universal ideas concretely universalisable. It will be self-defeating to remain stuck in an identity politics that is usually cast in a provincial orientation and narrow aspiration.

ALSO READ

Gopal Guru is co-author, most recently, of Experience, Caste, and the Everyday Social, is a political theorist and Editor, Economic and Political Weekly.