Summary of this article

Pressing on the importance of limits, Solanki reminds that the Earth is finite, and as are its resources.

Solanki talks of the AMG framework - Avoid first, Minimise second, Generate as last option

Climate communication fails when it becomes about guilt rather than understanding, he says.

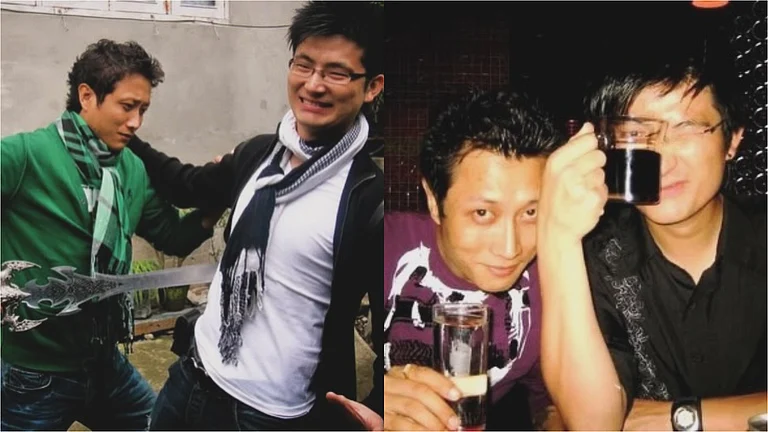

At the heart of Climate Change 2100 lies a deceptively simple question: can humanity survive without learning to live within limits? For physicist and climate educator Chetan Solanki, the answer depends less on governments and more on everyday choices. In conversation with Lalita Iyer of Outlook, Solanki discusses responsibility, resistance to the idea of limits, and why India’s climate future need not mirror the West’s past.

Q:You argue that climate change is less a problem of knowledge and more a problem of choices. At what point, in your view, does individual responsibility meaningfully intersect with structural and political failure?

A: I would say climate change is 90% a problem of individual choices and only 10% a problem of political or structural failure. Consuming more than the capacity of environment is the problem. And, consumption is made by individuals, not by institutions. Therefore, it is individual who is driving environmental degradation and climate change. Politics and markets largely respond to that demand.

Q: The book repeatedly returns to the idea of “limits” — to consumption, growth, and even aspiration. Why is the language of limits so difficult for modern societies to accept, particularly in countries like India?

A: Truth does not depend on whether we accept it or not — it is universal and binding. The Earth is finite, and all its resources are finite. Just as a fixed salary demands limits on spending, a finite planet demands limits on consumption. Modern societies struggle with this because for decades our parents, teachers, leaders, and institutions have told us that growth and consumption can continue without limits. Accepting limits today feels like questioning the very story we have been taught to believe.

Q: Your AMG framework (Avoid, Minimise, Generate) reframes climate action as subtraction rather than addition. What kinds of resistance—psychological or cultural—have you encountered to this way of thinking?

A: The biggest resistance comes from the belief that technology and policy will someday solve the problem for us. We are very comfortable adding solutions, but very uncomfortable subtracting consumption. Yet, just as prevention is better than cure, avoiding unnecessary consumption is far more powerful than any technological fix — even solar or electric vehicles. AMG framework (Avoid first, Minimise second, Generate as last option) challenges the comforting idea that we can consume freely and innovate our way out later.

Q: You suggest that the climate conversation often alienates people by moralising everyday behaviour. How can climate communication remain ethically urgent without becoming socially divisive or shaming?

A: Climate communication fails when it becomes about guilt rather than understanding. Most people are not irresponsible — they are simply unaware of the consequences of everyday consumption. Instead of shaming, we must explain the logic of limits and offer simple, doable choices. When people understand the connection between their life and the planet, change becomes voluntary, not forced. Just as we run away from a cobra because we understand it can kill us — not because it is written in the Constitution or taught in a classroom.

Q: India occupies a complicated position in the climate narrative—as both a developing economy and a major future emitter. What uncomfortable truths do you think India still avoids confronting honestly?

A: India’s situation is complicated, but it is also a historic opportunity.

We do not have to repeat the Western model of unlimited consumption and centralised growth. India can choose a development path that is more limited in scale, more local in nature, and more resilient to global shocks. The uncomfortable truth is that copying the old model will only lock us into future crises.

Q: The book ends not with certainty but with a question: survive or thrive. What would “thriving” actually look like in a climate-altered world, and how different would it feel from the lives we aspire to today?

A: Once we cross the storm of climate disasters, a thriving world will be more beautiful, more balanced, and built on a deeper sense of belonging. It will be a world where “I can afford, but nature cannot” becomes a personal dharma, and where the central question shifts from “How much can I take?” to “How little do I need for a healthy and happy life?” In such a world, success will no longer be measured by speed and accumulation, but by stability, sufficiency, and care.