Summary of this article

China ended 2025 with a historic trade surplus of nearly $1.2tn, driven by strong export growth even as imports remained subdued due to weak domestic demand.

Exports to the US fell sharply amid renewed tariffs, but China offset the decline by expanding trade with the EU, ASEAN, Africa and Latin America.

While exports of green tech, robotics and AI boosted growth, the widening surplus is intensifying concerns abroad over overcapacity and reliance on Chinese manufacturing.

China reportedly closed 2025 with a milestone: the largest trade surplus ever recorded by any country. Official figures released on Wednesday showed the surplus reached almost $1.2 trillion, underlining how effectively Chinese exporters have adapted to a tougher global landscape and how limited the impact of renewed US tariffs has been so far.

Crucially, the record was not built on sales to the United States. Instead, it reflected China’s accelerating expansion into other markets. As trade frictions with Washington sharpened following Donald Trump’s return to the White House, Beijing intensified a long-standing strategy to reduce dependence on the world’s biggest consumer economy. That shift towards Southeast Asia, Africa, Latin America and parts of Europe has clearly paid off.

Customs data show the trade surplus rose by about 20 per cent from 2024, crossing the $1 trillion threshold even before December. The final month of the year alone delivered a surplus of more than $114bn, one of the highest monthly figures on record driven by strong demand from the European Union, ASEAN countries, Africa and Latin America.

According to Xinhua, broken down by region, its import values from Asia, Latin America and Africa rose by 3.9 per cent, 4.9 per cent and 6 per cent, respectively, reflecting balanced development in import trade across different regions in 2025.

India–China trade grows, but imbalance deepens

Indian exports to China, which have traditionally struggled to gain traction, reached USD 19.75 billion between January and December last year. This marked a rise of 9.7 per cent, translating into an additional $ 5.5 billion, according to official data. Over the same period, Chinese shipments to India grew at a faster pace of 12.8 per cent, climbing to $135.87 billion.

The data also showed a sharp increase in India’s imports from China between November 2023 and November 2025, rising by an estimated 13–15 per cent. In November alone, India’s exports to China jumped dramatically by 90 per cent year on year to $2.2 billion. However, an analysis by the Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI) cautioned that this headline growth conceals the highly uneven and volatile nature of India’s export performance, alongside a deepening reliance on Chinese imports.

Between April and November, India’s exports to China expanded by 33 per cent to $12.2 billion, compared with $9.2 billion during the same period a year earlier. GTRI noted that the trade relationship has entered a phase marked by stark imbalances. Export growth, it said, is not widespread but largely driven by naphtha and a limited range of non-traditional electronics products, rather than India’s core export sectors.

Despite rising trade on both sides, total bilateral commerce surged to a record $155.62 billion in 2025. This milestone was reached in a year when both countries were impacted by tariff hikes introduced by US President Donald Trump. Meanwhile, India’s trade deficit with China , a persistent concern, widened to $116.12 billion, crossing the $100-billion threshold for only the second time since 2023.

Beijing credits green tech and advanced manufacturing exports

Wang Jun, deputy director of China’s customs administration, described the results as “extraordinary and hard-won” at a government press briefing, citing the “profound changes” reshaping global trade. He pointed in particular to rapid growth in exports of green technologies, robotics and artificial intelligence-related products, industries central to China’s long-term industrial strategy.

The export surge reflects a combination of international and domestic dynamics. Overseas demand for Chinese goods has remained resilient, supported by persistent inflation in Western economies, abundant industrial capacity and a relatively weak yuan, all of which have bolstered China’s price competitiveness. At home, however, the picture is far less robust.

Strong exports contrast with weak domestic demand

However, all is not well with China’s economy. It continues to be weighed down by a prolonged property downturn and rising debt. Businesses have held back on investment and consumers have remained cautious, resulting in subdued demand for imports. Imports rose by just 0.5 per cent last year, barely changing overall. That imbalance based on strong exports alongside flat imports has been a key factor behind the record surplus.

This means that exports grew by 6.1 per cent year on year to 26.99 trillion yuan in 2025. Imports reached a record 18.48 trillion yuan, also up 0.5 per cent, cementing China’s position as the world’s second-largest import market for the 17th consecutive year. Over the course of the 14th Five-Year Plan period from 2021 to 2025, China’s cumulative imports and exports exceeded 200 trillion yuan, a 40 per cent increase on the previous five-year period and an average annual growth rate of 7.1 per cent.

Trade with the United States, however, moved sharply in the opposite direction. Exports to the US fell by around 20 per cent in dollar terms during 2025, while imports from America declined by nearly 15 per cent. Tariffs imposed by the Trump administration cut China’s bilateral surplus with the US by more than a fifth. Chinese manufacturers responded by accelerating sales elsewhere and, in some cases, by routing goods through third countries in Southeast Asia to circumvent American trade barriers.

Exports to Africa surged by more than 25 per cent, shipments to ASEAN nations rose over 13 per cent, and exports to the EU increased by more than 8 per cent. In total, China recorded monthly trade surpluses above $100bn on seven occasions last year, compared with just once in 2024, a clear indication that US pressure has barely dented China’s wider global trade position.

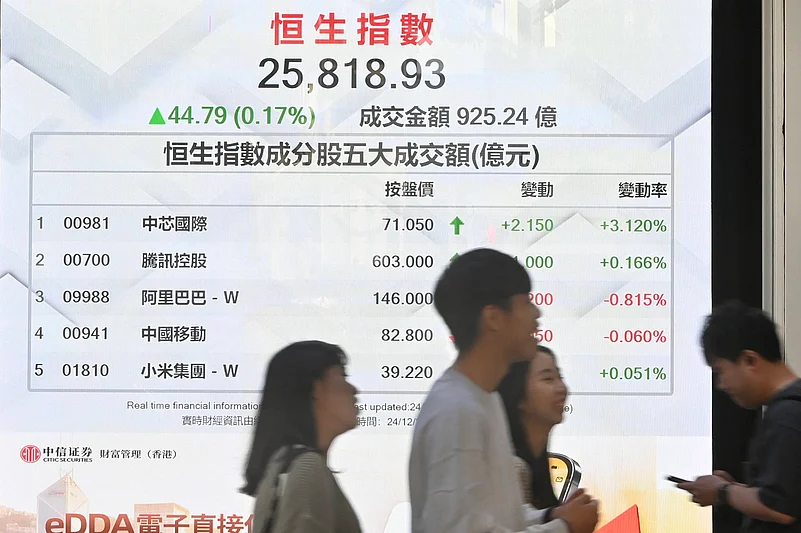

Financial markets reacted calmly. The yuan held steady, while Chinese equities advanced, with both the Shanghai Composite and the CSI 300 rising more than 1 per cent in morning trading.

Yet the achievement brings complications for Beijing. While export growth has supported jobs and industrial output, it also risks intensifying scrutiny abroad as governments face mounting pressure from domestic industries struggling to compete with Chinese products.

That scrutiny is already growing. As Chinese goods become more deeply embedded in global supply chains, concerns are rising in capitals around the world about overcapacity, trade practices and excessive reliance on China, particularly in strategic areas such as clean energy and advanced manufacturing.

Looking ahead to 2026, policymakers face a fundamental question: how long can the world’s second-largest economy continue to offset weak domestic demand by exporting ever-cheaper goods? China has relied heavily on foreign markets to counter its property slump and cautious consumers, but that strategy may become harder to sustain as resistance builds overseas.

For now, however, momentum remains firmly with China. With factories running at full tilt, exporters proving highly adaptable and markets well beyond the US increasingly within reach, the country has once again demonstrated why it remains the world’s manufacturing powerhouse and why its trade surplus, at least for the moment, continues to defy politics.