Summary of this article

Tarique Rahman's foreign policy mantra of “Bangladesh first” signals a desire to diversify partnerships rather than align exclusively with any single power.

Between 2016 and 2022, China invested approximately $26 billion in Bangladesh, much of it under the Belt and Road Initiative

With Beijing's investments totalling billions and the BNP's historic ties to China, Washington views a robust diplomatic presence as essential to preserving its own strategic interests

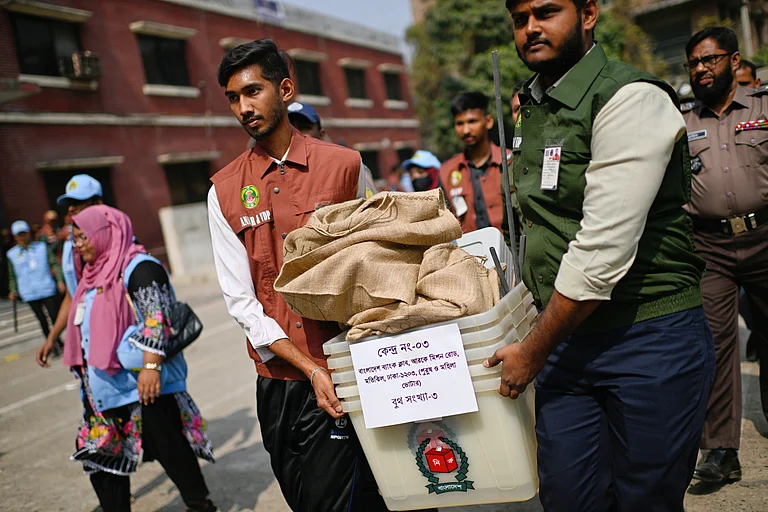

Two days after the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) secured a landslide victory in the February 12 parliamentary elections, the dust is finally settling on one of the most consequential political transitions in the nation's history. With 212 seats in the 299-member parliament, the BNP under Tarique Rahman has returned to power after nearly two decades in the political wilderness. The Awami League, which ruled for fifteen years under Sheikh Hasina, has been banned from the contest. The Jamaat-e-Islami-led alliance, which won 77 seats, will sit in opposition. The mandate is unambiguous. But what does it mean for Bangladesh's place in the world? How does the new Dhaka view its neighbours India, China, Pakistan, and its relationship with the United States? To answer these questions, one must listen not to campaign rhetoric, but to the signals emerging from BNP sources and the quiet diplomacy already underway.

For India, the BNP's victory is a moment of profound strategic anxiety. For fifteen years, New Delhi built its eastern neighbourhood policy around Sheikh Hasina's predictability. She delivered on security cooperation, transit access to the Northeast, and keeping a firm check on anti-India militant groups. In return, India offered unstinting political support and a studied silence on the steady erosion of democratic institutions inside Bangladesh. That era is over. And Dhaka's new leadership is signalling, with unusual candour, that the relationship must be rebuilt on fundamentally different terms.

The most immediate test arrived within 48 hours of the election results. The BNP has announced plans to seek the extradition of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina from India to face trial in Bangladesh. Senior party leaders have stressed that legal and diplomatic channels would be pursued according to international norms. Despite the demand, BNP has reaffirmed its commitment to maintaining friendly and respectful relations with India.

This is not sabre-rattling. It is a calculated diplomatic move, designed to signal to domestic constituents that justice for the July 2024 killings in which over 1,400 protesters died remains a priority, while simultaneously leaving room for negotiation with New Delhi. The BNP knows that extradition is legally complex and politically sensitive. But by formally raising the demand, it has placed the onus on India to respond, transforming a dormant issue into an active diplomatic agenda item. BNP sources outlined other clear priorities for the incoming government. Topping the agenda is the cessation of "border killings" by India's Border Security Force and renewal of the Ganga Waters Treaty, due before December 2026. BNP sources indicated that Dhaka would seek to conclude this treaty in a "fair" manner, signalling a departure from the previous arrangement that many in Bangladesh viewed as skewed toward Indian interests.

Yet despite these friction points, there is no appetite in Dhaka for outright hostility. The BNP has pledged continued cooperation on counterterrorism, resolution of the Teesta water dispute, and protection of Hindu minorities grounded in the principles of "equality" and "mutual respect." The message from Dhaka is clear: India is an inescapable neighbour, essential for trade, transit, and regional stability. But the era of deference is over. The new relationship will be transactional, pragmatic, and conducted on terms of sovereign equality, not the big brotherism that characterised the previous regime. The extradition demand, far from being a deal-breaker, is best understood as the opening bid in a long negotiation.

If India is the complicated neighbour, China is the strategic hedge. The BNP's relationship with Beijing is long-standing, predating even the party's founding. Ziaur Rahman established full diplomatic relations with China in 1975, soon after Bangladesh's independence, and between 1975 and 1980, China supplied 78 per cent of Bangladesh's weapons.

That historical bond has been carefully nurtured in the lead-up to this election. Throughout 2025, high-level BNP delegations travelled to Beijing at the invitation of the Communist Party of China, meeting with CPC Politburo members and discussing bilateral cooperation. In January 2026, just weeks before the election, Chinese Ambassador Yao Wen met Tarique Rahman to discuss "China-Bangladesh relations and party-to-party cooperation." The economic stakes are enormous. Between 2016 and 2022, China invested approximately $26 billion in Bangladesh, much of it under the Belt and Road Initiative, including infrastructure projects like the modernisation of Mongla Port. A BNP government is expected to consolidate these investments and potentially expand them.

But this is not a zero-sum game. BNP leaders have consistently framed China as a hedge against excessive dependence on India, not as a replacement for it. Tarique Rahman's foreign policy mantra of “Bangladesh first” signals a desire to diversify partnerships rather than align exclusively with any single power. The BNP could maintain close defence ties with China and pursue rapprochement with Pakistan, a calibrated pursuit of diversified partnerships and strategic autonomy, not exclusive alignment with any single power. Pakistan's leadership was quick to congratulate the BNP on its victory. Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif expressed his desire to "work closely with the new Bangladesh leadership to further strengthen historic, brotherly multifaceted bilateral relations and advance shared goals of peace, stability, and development in South Asia.

This diplomatic warmth follows tangible steps toward normalisation. Since the 2024 uprising, the two countries have restarted sea trade and expanded government-to-government commerce. During Bangladesh's recent standoff with India over cricket when the Bangladesh Cricket Board requested its T20 World Cup matches be shifted from India, and the ICC responded by expelling Bangladesh, Pakistan offered immediate solidarity, initially boycotting its own match against India before withdrawing the boycott at Bangladesh's request. For Dhaka, the Pakistan outreach serves multiple purposes. It signals strategic autonomy from India, opens new economic opportunities, and resonates with domestic constituencies that view improved Islamic-world ties favourably. But it is not without risks.

Amid these regional recalibrations, Washington has moved swiftly to secure its position. US Secretary of State Marco Rubio congratulated the BNP and Tarique Rahman on their victory, emphasising that the United States looks forward to engaging with Bangladesh's newly elected government to advance regional prosperity and security. This public warmth follows months of quiet diplomacy. During the campaign, the US engaged not only with the BNP but also with the Jamaat-e-Islami, a striking departure from Washington's traditional stance against political Islam. The US outreach is driven by a single overriding concern: countering China's rising influence in Bangladesh. With Beijing's investments totalling billions and the BNP's historic ties to China, Washington views a robust diplomatic presence as essential to preserving its own strategic interests in the Bay of Bengal region. For Dhaka, the US relationship offers an additional layer of strategic depth, a counterweight to both Indian and Chinese influence, and access to markets and technology.

For all the focus on geopolitics, the new government's most immediate challenges are domestic. The Gen Z protesters who brought down Hasina in 2024 did not take to the streets because of China's Belt and Road or India's Act East policy. They took to the streets because they could not find jobs, because their degrees qualified them only for unemployment lines, because the economy had failed to generate dignified work for millions of young Bangladeshis. The BNP's manifesto promises five million new jobs and a trillion-dollar economy by 2040. But the structural problems are daunting: slowing growth, foreign exchange pressure, inflation, youth unemployment, and uncertainty in the garment sector, which remains the backbone of the export economy. Restoring investor confidence, delivering IMF-mandated reforms, and stabilising the currency will stretch the new government's administrative capacity.

Equally challenging will be assuring the safety of religious minorities while managing the BNP's historical ties with Islamist groups. Any failure to prevent communal violence against the Hindu minority would not only rupture social cohesion at home but also reverberate across the border, straining ties with India. What emerges from Dhaka's post-election calculations is a coherent foreign policy doctrine. Call it "Bangladesh First”, Tarique Rahman's own formulation. It is not anti-India, not pro-China, not aligned with Washington or Islamabad. It is a doctrine of strategic autonomy, of diversified partnerships, of relationships conducted on terms of mutual respect and sovereign equality.

Rabiul Alam is a Dhaka-based journalist.

Views expressed are personal.