Summary of this article

Both the BNP and Jamaat have signalled a desire for independent, balanced and mutually respectful ties with New Delhi

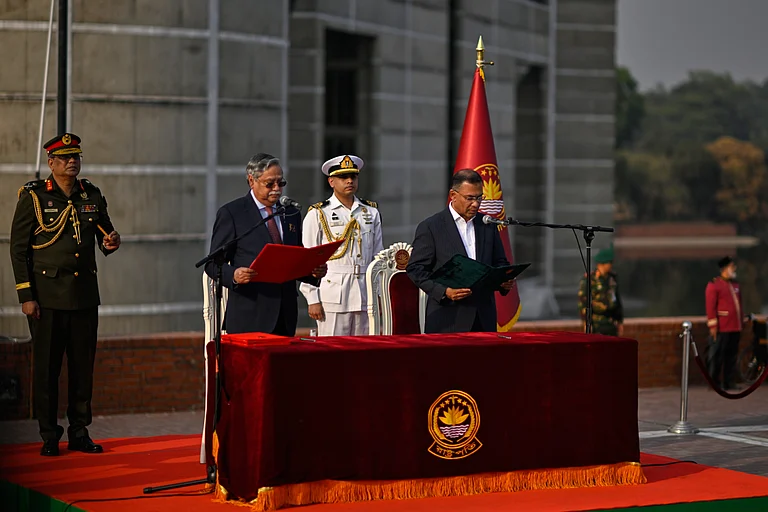

Bangladesh will also hold a national referendum to give people a chance to vote on reforms to State institutions

Whoever wins, the morning of February 13 will bring not triumph but responsibility.

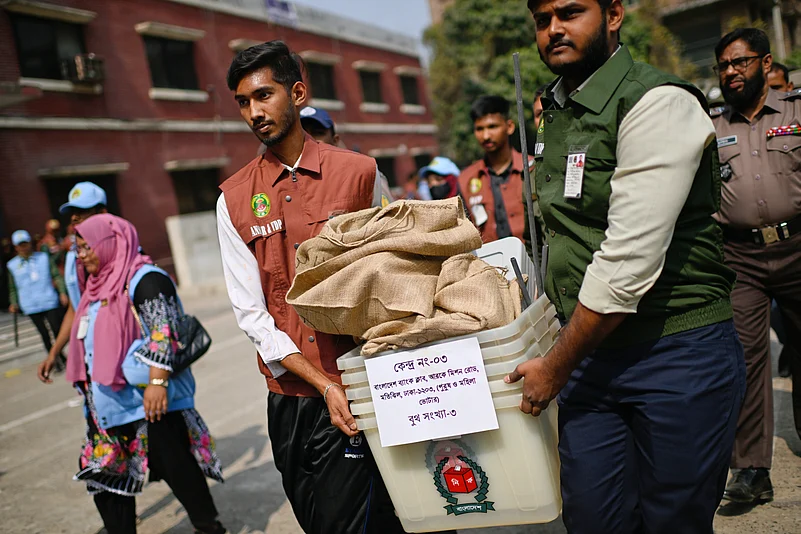

On February 12, 127 million Bangladeshis walked into polling stations across a nation of 170 million people. They cast ballots not merely for a new parliament or a new prime minister. They also, whether they knew it or not, were delivering a verdict on the future of South Asia's geopolitical architecture. This is not hyperbolic framing. For the first time in over a decade and a half, the Awami League, the party that many believed served as New Delhi's unflinching anchor in Dhaka, was absent from the ballot. In its place, two forces with historically cooler ties to India, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Jamaat-e-Islami-led alliance, were locked in a fiercely competitive race.

The outcome will determine not just who governs Bangladesh, but how this nation of immense strategic weight navigates its relationships with the three powers watching this election more keenly than any other: India, China, and the United States. The country will also hold a national referendum to give people a chance to vote on reforms to State institutions which focuses on implementing the 'July Charter' drafted after the 2024 uprising to establish good governance, democracy, and social justice through institutional reforms, and to prevent “recurrence of authoritarian and fascist rule”.

Eighteen months ago, Bangladesh witnessed something few believed possible. A student-led uprising, powered by Gen Z's fury and fuelled by social media, toppled Sheikh Hasina, a prime minister who had ruled for fifteen years with an iron fist. The Monsoon Revolution was not a coup, not a foreign conspiracy, not a colour revolution exported from anywhere. It was a spontaneous combustion of a young generation that had run out of patience. What did they want? Not manifestos, not party flags, not the familiar faces of ageing politicians. They wanted jobs. They wanted an end to quota systems that reserved half of government posts for the children and grandchildren of 1971 veterans.

They wanted streets where girls could walk without fear of harassment. They wanted a Bangladesh that did not treat its brightest minds as export commodities to be shipped to Gulf construction sites. They wanted, above all, dignity. The regime fell in thirty-six days. Hasina fled in a military helicopter, touching down in Delhi, where she remains to this day. Her departure was not mourned. Her party, the Awami League, was banned from contesting this election. And yet, her ghost haunts every rally, every manifesto, every bitter exchange between the BNP and Jamaat-e-Islami. Because the question that drove the students to the streets in July 2024 remains unanswered: What comes next?

For India, Hasina's ouster was not merely a political inconvenience. It was a strategic earthquake. For fifteen years, New Delhi had built its eastern neighbourhood policy around a single, simple proposition: Sheikh Hasina is predictable, she is pliable, and she will not align with China. In return, India offered unstinting political support, generous lines of credit, and a studied silence on the steady erosion of democratic institutions inside Bangladesh. The three elections, in which Hasina's party won amid widespread boycotts, allegations of ballot stuffing and voter intimidation, elicited barely a murmur from South Block. This conflation of person with nation was always fragile. When the dam broke, India found itself on the wrong side of history, standing with a deposed leader while a generation of Bangladeshis celebrated her fall.

The interim government's subsequent moves were read in New Delhi as deliberate provocations. Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus chose Beijing for his first state visit. In January, China signed a defence agreement to build a drone manufacturing facility near Bangladesh's border with India's chicken's neck corridor. Direct flights to Pakistan resumed after fourteen years. Dhaka signalled, quietly but unmistakably, that the era of automatic deference to Indian interests was over. Yet this is not, as some in New Delhi fear, a zero-sum game. Bangladesh is not pivoting away from India so much as it is finally asserting the right to have multiple friends and multiple options. The notion that Dhaka must choose between Delhi and Beijing is a relic of Cold War thinking that serves neither capital, neither country, neither people.

The question, therefore, is not whether the next government will engage with India it must, for geography is immutable but on what terms. Both the BNP and Jamaat have signalled, in their manifestos and in private engagements with diplomats, a desire for independent, balanced and mutually respectful ties, not subordinating national interests. With election one night away, Dhaka’s neighborhoods, still chanting “Delhi na, Dhaka? Dhaka, Dhaka” means a lot. This is not merely rhetoric. It reflects a widespread conviction among Bangladeshis particularly the young that India supported, enabled, and prolonged a regime that stole their futures. Whether this perception is entirely fair is beside the point. It is real, it is deeply felt, and it will not be dispelled by diplomatic platitudes or carefully worded joint statements.

However, no discussion of Bangladesh-India relations can avoid the question that has become its dimension: the safety of the Hindu minority. The surge in violence against Bangladesh's Hindu community since the interim government took charge is undeniable and deeply troubling. India's condemnation of what it terms “unremitting hostility against minorities” is morally valid. Yet Dhaka accuses New Delhi of exaggerating the scale for political ends and of weaponising minority safety as a diplomatic cudgel. Each public censure from India reinforces a narrative inside Bangladesh: that New Delhi views Hindus in Bangladesh as its own citizens, and therefore as a fifth column. This perception, however unfair, fuels the very anti-India sentiment India seeks to combat. The victims, meanwhile, are caught in a merciless squeeze. Once a reliable Awami League vote bank, the Hindu community now finds itself politically orphaned.

Amid the geopolitical manoeuvering, the voices that actually changed Bangladesh risk being drowned out.

The Gen Z protesters of 2024 were not foreign policy analysts. They did not take to the streets because of China's Belt and Road Initiative or India's Act East policy. They took to the streets because they could not find jobs. Because their degrees from public universities qualified them only for unemployment lines. Because the economy, despite impressive GDP numbers, had failed to generate dignified work for the millions of young Bangladeshis entering the labour market each year.

What they want now is not complicated. They want an economy that works for them. They want public universities that teach skills, not just ideology. They want a civil service selected by merit, not by family connections or political loyalty. They want a Bangladesh that does not treat its brightest young people as surplus population to be exported to construction sites in Middle eastern countries and factories in Malaysia. The manifestos of both major parties pay lip service to these aspirations. The BNP promises five million new jobs and a trillion-dollar economy by 2040. Jamaat pledges to create 1.5 million freelancers and 500,000 new entrepreneurs within five years. Yet neither document explains, with any specificity, how these targets will be met.

As people are returning to villages to cast ballots across Bangladesh, for India, this election represents not a threat but a test one it has been failing in recent months, but one it can still pass, engaging with the newly elected governments. People of this country hope New Delhi abandon the fiction that Bangladesh's democratic choice is somehow illegitimate if it produces a government not to its liking.

Whoever wins, the morning of February 13 will bring not triumph but responsibility. The new prime minister will inherit a nation with immense potential $2 trillion economy in waiting, a demographic dividend, a strategic location that three global powers covet. But they will also inherit a relationship with India that is bruised, suspicious, and in urgent need of repair. The question is whether both sides possess the wisdom to seize this moment not as a defeat for one or victory for another, but as an opportunity to build a mature partnership, one based on equality, mutual benefit, and the quiet acknowledgment that in South Asia, geography is destiny.

Rabiul Alam is a Dhaka-based journalist.

Views expressed are personal