The following piece discusses how Indian cinema has long used superheroes to address injustice, power, and relationships.

Lokah’s debut chapter launches a five-part universe featuring strong performances.

The genre’s evolution leads to Malayalam cinema’s first super-heroine, Chandra in Lokah Chapter 1.

When Dominic Arun’s Lokah Chapter 1: Chandra (2025) premiered, it felt like the culmination of a long cultural wait. For decades, Indian cinema flirted with the idea of superheroes, but rarely produced one that felt rooted, resonant, and particularly female. Here was a figure neither derivative of Western blueprints nor folkloric anomaly, merging mythology with contemporary anxieties, and ample character depth. Lokah arrived with an ambition that aligned itself against Hollywood’s global franchise standards, matching them in scale and narrative sophistication. Kalyani Priyadarshan’s Chandra signalled a long overdue shift in how India actually imagines power. To understand Lokah, one must trace its roots, cross-countering the traditions that preceded it and reflecting on why it took so long for Indian cinema to produce a female superhero who feels fully realised.

Thematically, what unites Chandra and her Indian superhero predecessors oscillates between myth and social realism. Here, the chosen one is granted divinity for the greater good—to fight for those who are wronged or oppressed. Earlier, socially grounded films like Mr. India (1987) offered Arun (Anil Kapoor) invisibility to fight corruption and protect orphans. This brings out a sub-section of superheroes who aren’t just defeating the obvious enemies but actually interrogating the larger systems that fail ordinary citizens. Vikramaditya Motwane’s Bhavesh Joshi Superhero (2018) explored the chaos of Mumbai’s corrupt politics and its water scams. Instead of shiny superhero-suits or divine powers, it planted itself in the immediacy of urban grime, borrowing the language of vlogs and street protests. Lokah too, while much more myth-oriented, grounds itself within the grotesque realities of gendered power, sexual harassment and organ trafficking.

While some superheroes grappled with serious, grown-up themes like socio-political injustices, many films and TV shows still treated these figures as companions for children, often imagining kids as their primary audience. Sonpari (1993-1997), though not strictly a superheroine, revolved around a young girl befriending a mystical fairy. However, in a show named after her, her presence was primarily supportive—aiding the child protagonist rather than being a central hero in her own right. Contrarily, Kalyani Priyadarshan’s Chandra is not as softened but magnetic, grand, and unapologetically in charge.

Prior to this came Shaktimaan (1997-2005) who wasn’t just a superhero, but a full-time moral science tutor in spandex. In trying to guide a new generation with nationalist sermons, Shaktimaan always built himself up as more guru than human—emotionally distant and “superior” from those who looked up to him. Milind Soman’s Captain Vyom (1998) was India’s attempt to look the West in the eye and say: we can do sci-fi too. Vyom was a disciplined man elevated by training and tech—a poster boy for post-liberalisation India’s dream of catching up with American futurism. Both, however, were still trapped in the same patriarchal script: the ideal Indian male saviour framed as the spectacle of power, women circling the story as love interests, villains or visual props. Their enemies were galactic and abstract, conveniently “out there,” far from the grotesque politics of the common man’s life. This is why Chandra in Lokah feels like such a shift. She isn’t preaching morality or nationalist pride but embodies a mythic-psychological heroism. Her powers are both functional and symbolic, rooted in Kerala’s folk heritage yet refracted through urgent modern anxieties. Moreover, Chandra subverts the often villainised transgressive woman (Yakshi or witch) as a saviour of the people. In an instance within the film, she’s also prophetically told, “God has chosen you to fight for the helpless and the hunted.” By bringing up the generationally oppressed, Arun taps into a distinctly Indian uneasiness: heroism exists not in isolation, but through everyday actions and responsibilities one bears toward the community.

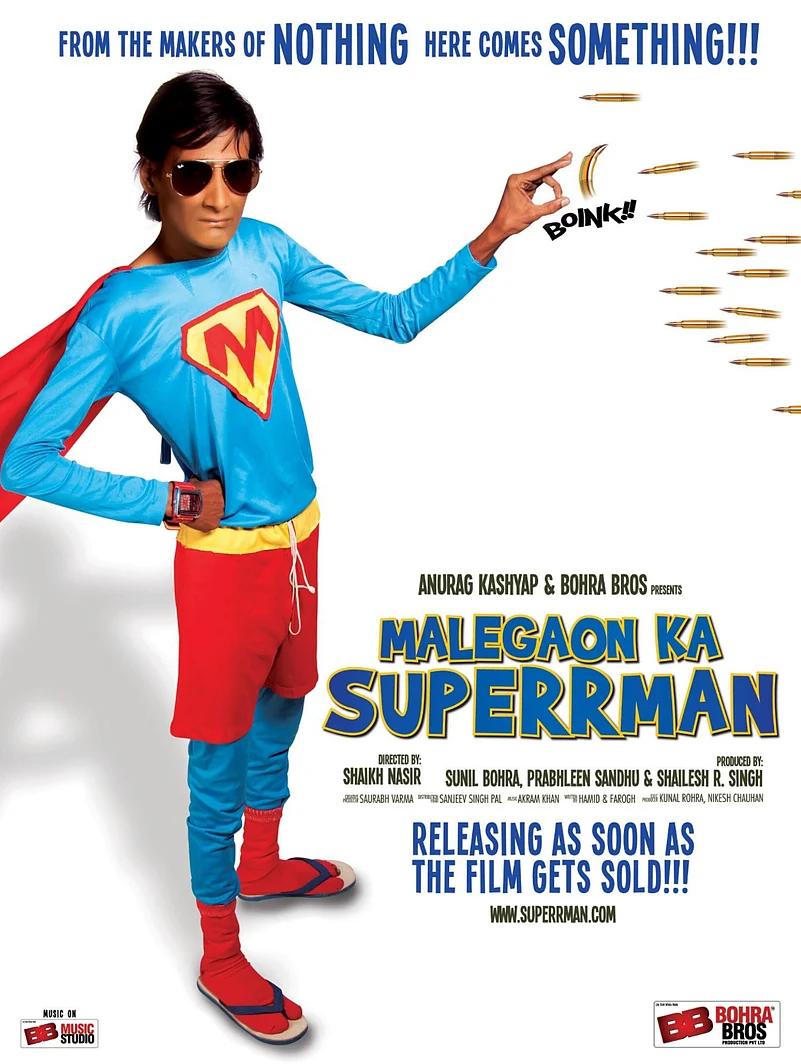

When India tried its luck adapting a superhero from the West, it ended up with countless renditions of Superman. Regionally, thematically, and narratively Indianised, Superman travelled far and wide, more than any other superhero. And while most Indian adaptations leaned on global familiarity or spectacle to capture audience attention, Chandra demanded belief in her own story. But what truly appeals to the masses about Superman—or any hero? Is it their ability to restore order in a chaotic world, or their relentless kindness that draws us closer and makes us believe in them? Regional and comic adaptations, like Nasir Sheikh’s Malegaon Ka Superrman (2009) proved that audiences relish seeing global icons reimagined through local humour and social context. This version of Superman was less about invincibility and more about relatability—a hero who could stumble, laugh, and still save the day. That same triumph is visible in Lokah, where sly bursts of humour between Chandra and the trio cut through the gravity of the narrative without undercutting its stakes.

Regional cinema has achieved the authenticity that Bollywood has often failed to. Audiences accustomed to Hollywood films and CGI excess see that visual sophistication can coexist with narrative gravity, reshaping expectations for Indian blockbusters. Lokah’s triumph, however, is as much thematic as it is technical. Its visual effects are significant, without ever appearing boastful or interfering with the narrative. This balance becomes clearer when viewed against other recent Indian superhero experiments. Minnal Murali (2021), another Malayalam superhero film set in a village in the 90s, features Tovino Thomas as an aspiring fashion designer, Jason. The film is often compared to Lokah for its rooted characters, spaces and humour—placing extraordinary powers within everyday textures. Earlier big-budget experiments in myth-based films. like Brahmāstra and Adipurush (2023), prioritised showing off scale and VFX over storytelling-backed characters. Meanwhile, Bollywood also often sidelined women in superhero films—like Priyanka Chopra in Krrish (2006-2013), Kareena Kapoor in Ra.One (2011) or Alia in Brahmāstra (2022)—as mere muses or damsels in distress.

Lokah reframes this dynamic dramatically. It bridges two traditions. On one side, it inherits the groundedness of Minnal Murali—the warmth of small-town humour, the intimacy of lived-in spaces, and characters whose flaws remain in plain sight. From its big-budget Hindi predecessors, it borrows the visual audacity to actually create something that competes with global standards. Crucially, it never loses sight of character. Chandra is a badass, autonomous heroine, commanding both cinematic gaze as well as narrative agency. Audiences respond to such figures differently: with a mix of admiration, aspiration, and curiosity—quietly signalling a shift in how power and gender converge on the big screen.

Traditionally, superhero films have always relied on the binary of good versus evil, which often clearly labels protagonists and antagonists into archetypes with little room for complexity. One of Lokah’s few follies is in the way it completely flattens its villain. Inspector Nachiyapa Gowda (Sandy) is a cardboard cut-out villain with no nuance or backstory that explains his pure evil. A misogynist needs no reason to be one, though in contextually richer superhero films, villains aren’t just obstacles; at times, they are distorted reflections of the hero’s own flaws and a reminder of what they could become. Antagonistic figures may also often reflect larger societal anxieties and act out as a response to oppression or threat to their own lives, instead of sheer malice. For example, the AI-villain in Ra. One played by Arjun Rampal initially appears destructive, but actually evolves to mirror human-created biases, echoing the idea that being a villain can be more systemic rather than personal. In Minnal Murali too, what makes Shibu (Guru Somasundaram) striking as an antagonist is that he isn’t born evil but shaped into it. The same powers once placed him alongside a hero, yet choices, fate and consequences set them apart. In the same vein, one is reminded of Spiderman’s mantra: “With great power comes great responsibility.” In The Amazing Spiderman (2012) Peter Parker’s promise to Gwen Stacy’s father introduces moral conflict: he’s bound to protect her, yet his double life as a vigilante hero makes danger unavoidable. This adds to the lifelong guilt he carries of being responsible for her death. These arcs are reminders that superheroes (and villains) resonate most when they grapple with consequence, rather than being invincible.

As Lokah unveils its five-part universe, it brings in opportunities as well as the optimism to make room for more nuanced characters and greater conflicts ahead. Though the franchise-debut has its own flaws, its success feels both deserved and long overdue. Pan-Indian audiences, shaped by regional storytelling sophistication, have already shown through Malayalam and Marathi cinema that they value character-driven, socially conscious, and mythically coherent films. Lokah demonstrates that mythology can intensify realism rather than dilute it, positioning myth as the future of Indian superhero storytelling. Anand Gandhi and Zain Memon’s Maya Narrative Universe too, proposes myth as capable of carrying contemporary and futuristic concerns, while resonating globally. Indian cinema, long in conversation with Hollywood and its own traditions, now stands on the threshold of a superhero-form that is rooted yet expansive. Lokah is both mirror and promise—heralding a future where regional heroines and queer superheroes emerge, power is redistributed, and imagination finally outpaces history.