Summary of this article

The Story of Sisterhood is produced by Zubaan under its Cultures of Peace program, in collaboration with the Heinrich Böll Stiftung and the Sisterhood Network itself.

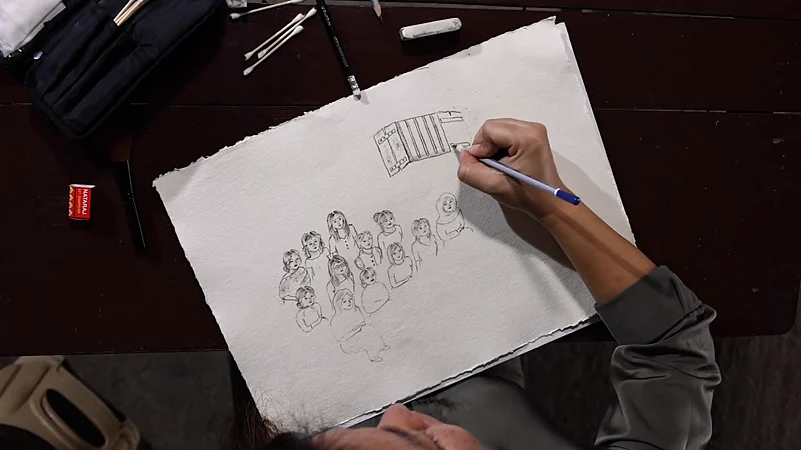

The film is scripted and directed by Anungla Zoe Longkumer.

By foregrounding the collective labour that's the backbone of the network’s work, the film emphasises how women’s lives are inherently political, shaped by both structural violence and sustained resistance.

In the early 2000s, when Nagaland was still deeply entrenched in traditional gender roles, and women faced acute economic instability, a local women’s collective called the Sisterhood Network emerged. Today, this network is the subject of The Story of Sisterhood, a documentary produced by Zubaan under its Cultures of Peace program, in collaboration with the Heinrich Böll Stiftung and the Sisterhood Network itself. The film, scripted and directed by Anungla Zoe Longkumer, centres on the work of this Nagaland-based women’s organisation, tracing its journey from inception to its present-day impact.

As a non-fiction work, The Story of Sisterhood not only archives women-led community initiatives but also offers insight into the larger socio-economic histories of Nagaland and the gendered roles embedded within it. According to the producer's note, "By foregrounding women’s everyday labour—artistic, culinary, caregiving—and the collective labour that forms the backbone of the network’s work, the film emphasises how women’s lives are inherently political, shaped by both structural violence and sustained resistance."

The film, part of Zubaan’s Cultures of Peace program—an initiative aimed at documenting and sharing histories from the margins—is one of the many projects through which Zubaan negotiates women’s histories within broader conversations on resilience, determination and social upliftment. Set against the backdrop of Nagaland’s extreme economic fragility, nationalist movements and prolonged military unrest, the documentary foregrounds the emergence of a Naga feminist movement rooted in collective care and economic self-determination.

Led by figures such as Alongla Aier, the Sisterhood Network sought to shift women’s economic power by listening to voices that were often suppressed and consistently relegated to the margins. What began as an initiative to facilitate unemployed homemakers in achieving financial independence gradually expanded into a broad-based institution. The network went on to train women, not limited to homemakers, in culinary skills, tailoring, handicrafts, and also provided remedial education to children. From raising funds by baking cookies to contributing small amounts of money, weaving products, and eventually marketing them, the documentary conveys a convincing sense of empowerment among women in Naga society. The network’s work now spans 19 villages across Nagaland, supporting traditional economic activities like weaving, indigenous food production and jewellry-making, while fostering economic independence and challenging deep-rooted gender roles.

The documentary serves as a medium through which some of the most impactful yet marginalised labour of women becomes part of public history. It prompts reflection on why women’s movements are rarely as visible in public memory as other movements of similar significance. Both the work of the Sisterhood Network and the documentary itself bring these questions to the forefront—an intervention especially crucial now, as women across rural and urban spaces continue to experience unemployment, illiteracy and economic dependence, making them vulnerable to various forms of abuse.

In Naga society, women’s everyday labour is largely centred around agriculture. Throughout the year, they spend long hours working in the fields, an immensely labour-intensive practice. A persistent sense of guilt over not contributing monetarily to their households has historically compelled Naga women to take on strenuous responsibilities such as agricultural labour, pig rearing and domestic work. While these efforts undoubtedly sustain families, they come at the cost of invisibilising women’s identities. The Sisterhood Network intervenes precisely here: it not only leverages on women’s existing skills, but also introduces them to a working economy that fosters identity, dignity and self-esteem by adding value to long-neglected forms of labour. This empathetic intervention is what the documentary carefully foregrounds.

Despite remaining largely outside formal economic structures, where earnings are neither constant nor stabilised, women associated with the network can participate in and contribute to the state economy through a skill enhancement program. While the network works towards restoring women’s identities, the documentary simultaneously makes a powerful attempt to reclaim women’s histories and situate them within social discourse. One pivotal mindset shared by filmmaker Longkumer exemplifies this commitment. During post-production, she was insistent on engaging a woman professional as the editor, eventually bringing in one for it, from Kolkata. Thus, the effort to make women’s histories visible extended beyond the film’s narrative into the very ecology of its production.

By historicising the network’s work across regions such as Dimapur, Peren, Newland and Chümoukedima, the documentary also traces the mobility these women experienced within national and transnational spaces. From exhibiting and marketing products in Delhi and Madhya Pradesh to achieving upward economic mobility and receiving training abroad, the film highlights the scale of the network’s impact on women from the margins. As one participant notes, “Living off the backs of others brings no peace of mind, but earning a living through your own sweat and tears, raising your children yourself and paying for your own maintenance, that is how you live a good and happy life.”

The film further exposes how cases of domestic violence are rarely registered, and even when they are, perpetrators are often not jailed due to women’s financial dependence on them. By engaging with such government records and testimonies from direct beneficiaries, the film moves beyond documentation to powerfully establish the transformative intervention of the Sisterhood Network in Nagaland.

Documentary filmmaking in Nagaland has, over the years, functioned as both an archive of memory and an apparatus of socio-cultural critique. The Story of Sisterhood reinforces why non-fiction filmmaking remains central to the region, which is marked by layered histories, collective experiences and narratives long excluded from dominant discourse.