Summary of this article

Emotional labour in relationships is inherited and normalised, not freely chosen

When women say no to this invisible work, the backlash is swift

It is unpaid emotional caretaking that women are rejecting—not love

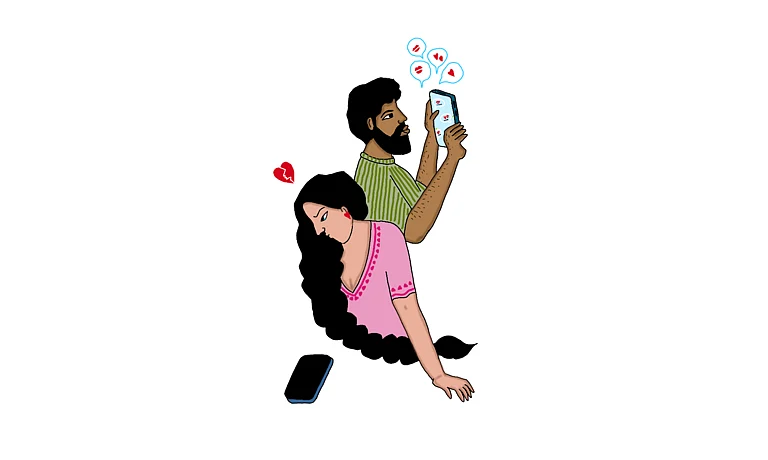

The recent piece in The New York Times on “mankeeping” finally put language to a form of labour women have long been performing without recognition. Not caregiving or homemaking. But the invisible, ongoing work of managing men’s emotional lives—holding their moods, anticipating their loneliness, softening their failures, absorbing their silences. The word resonated because it articulated something many women already knew but were never encouraged to name as work.

For most women, emotional labour does not arrive as a conscious choice. It arrives as inheritance.

“When you hear the term emotional labour in relationships, what does it bring up for you?” I ask Namrata. Her response goes immediately to her mother. “My mother—an utterly self-reliant, no-nonsense woman who has seen enough conflict in her life—told me before I got married, ‘Remember, it’s always the woman of the house who keeps things together, especially relationships.’” The advice wasn’t framed as injustice. “I remember agreeing because I had seen that everywhere I looked, within and outside my family.” Emotional labour was presented as inevitability.

She also remembers making a decision alongside that agreement. “I also remember deciding, in the midst of agreeing with mom, that I am never going to go above and beyond in order to ingratiate myself with my partner’s family. Match what I get and not a bit more.” Even that felt like restraint rather than refusal. Because emotional labour isn’t just about big gestures; it’s about the daily calibration of behaviour.

What follows, Namrata says, is “everything that isn’t tangible in a relationship.” The propping up of male insecurity. The soothing of maternal jealousy. Watching what you say in front of or about members of the family who aren’t on “your side.” Ensuring your kid doesn’t praise your cooking too favourably in their paternal grandparents’ home. Not letting your conflicts spill over onto your child, especially those happening with your partner. “Constantly assessing every room you walk into to ensure that your relationship feels supported and not abandoned.” The emotional labour always had to be at the front and centre of your life, she realised.

This expectation of calibration is rarely named outright, but it is widely understood. As Pooja puts it, women are expected to be “the gentler one” in every relationship—less shouty, more composed, endlessly calm. They are meant to keep households running without expecting help, stay connected to relatives, act as emotional anchors for their spouse’s parents even when the relationship is strained. Within marriages, she says, women are expected to be more understanding, more adjusting, because “men are men”. Anger and meanness are allowed emotions for them. For women, they are treated as disturbances—because a woman’s anger is seen as something that breaks the peace of the home, she says.

“Exhausting. Never ceases,” Namrata affirms. And when you stop—keeping the peace, tolerating certain things, or even simply reciprocating exactly what you get from others—ahh, the questions, the side eye…”

For Aparna, who is hanging on to a 21-year-old marriage, that exhaustion has crossed into something more damaging. “Opting out of emotional caretaking would mean to not be doing all the work alone emotionally,” she says. “Right now, I feel like I am the only one that has feelings or emotions.” In her relationship, talking about distress is immediately reframed. Talking about anything that bothers her is seen as creating a scene. “I’ve been told I only find things to complain about,” she says.

The criticism is constant. “When things go wrong or not according to plan, somehow, it’s always my fault. The constant criticism has broken me.” Being a homemaker compounds the erasure. “Whenever I want to talk about something important, I’ve been told I am in the middle of work. This minimises what I feel because I don’t “work” and apparently, I am not letting him work.”

What Aparna names clearly is how emotional labour becomes punishment when paired with avoidance. “Emotional caretaking for an avoidant is a punishment on the partner.” Over time, she began to recognise the pattern: “The manipulation, the breadcrumbing.” And the wider cost: “When people who need therapy don’t go to therapy, the victims end up needing help.”

She recalls watching Haq recently. “The gaslighting really triggered me. Most men sadly are like that. It doesn’t matter how educated, suave, charming, kind they are to the outside world. Within the four walls of their home, they just become completely different people.” And then the most isolating part: “No amount of relaying your version to people will have them believe that you get to experience this side. Because only you see it.”

It is only after this kind of cumulative exhaustion that the rise of the so-called self-absorbed woman in popular culture begins to make sense.

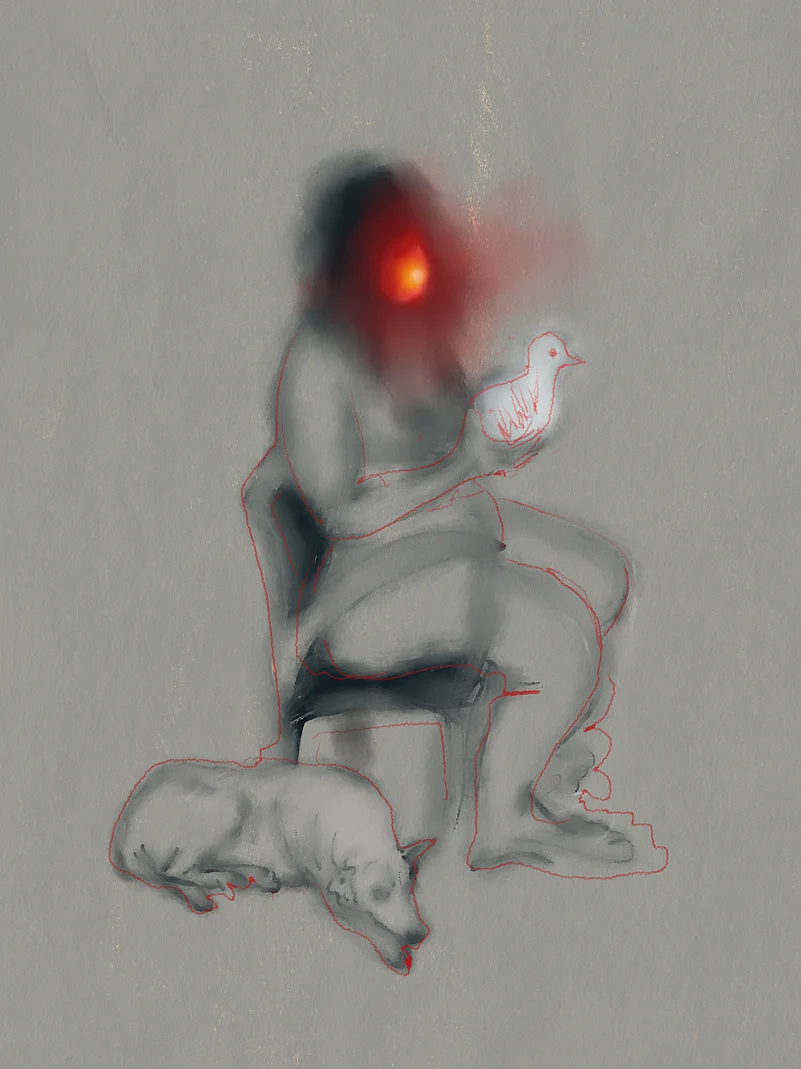

From Girls to Fleabag to Emily in Paris and Envious, these women are often read as narcissistic or morally suspect. But seen through the lens of mankeeping, their self-centering looks less like indulgence and more like refusal. They opt out of emotional caretaking. They choose themselves without apology or narrative redemption. What culture once punished as selfishness is now tentatively being reframed as agency—not because these women are admirable, but because the labour they refuse has finally been named.

Still, as Namrata points out, popular culture’s sympathy is limited. “There was a time when it did feel that pop culture and mainstream narratives had more space for women who chose themselves, but Bollywood’s approach has always been performative.” Even now, she says, female autonomy is conditional. “You have to be so damn good in order to be somewhat excused from being questioned on your path.” With trad content flooding screens, she feels we are in a more regressive moment for women’s choices.

Priyanka’s experience offers a quieter, lived alternative. Asked how emotional labour has changed for her the second time around, she is clear. “Yes, my expectation around emotional availability has changed a lot. I don’t settle for less anymore.” She still accommodates, she says, but “I expect a lot in a healthy way too.” What that has brought her is relief. “There is a relief, yes, I feel free.” In her current marriage, she says, “I experience what truly I believe is the goal of a relationship—freedom.”

Leena, recently out of a 25-year marriage, brings the conversation back to structure rather than sentiment. “There is no such thing as an equal relationship,” she says. “It is always lopsided.” Some days, one person is burnt out, some days the other is. “The challenge lies in waking up every day and choosing the person opposite you.” What matters is identifying what is negotiable and what is not. “For me, loyalty was non-negotiable.”

She is unsparing about how women end up carrying emotional labour. “The reason women get saddled with emotional labour in relationships is because we choose it. We don’t have boundaries and most of us are brought up with the romanticisation of sacrifice—through conditioning, books and movies.” And, she adds, “with sacrifice always comes resentment.”

At the same time, she resists the idea that choosing oneself alone is the answer. “The other scenario in which women always choose themselves is also lopsided. ‘My way or the highway’ cannot be the foundation of a healthy relationship.” She has finally begun to see with great clarity what one should look for in a partner, when people ask her. “Someone who does their own self-work—who takes the onus for their own happiness,” she says.

Perhaps that is where the conversation finally needs to land. Not in glorifying refusal, and not in romanticising endurance, but in dismantling the assumption that women must hold men—and relationships—together at all costs. The women who stop mankeeping are not rejecting love. They are rejecting unpaid, endless emotional labour. And in doing so, they are asking a question that still makes many people uncomfortable: what if love did not require women to disappear?

(Some names have been changed)