Summary of this article

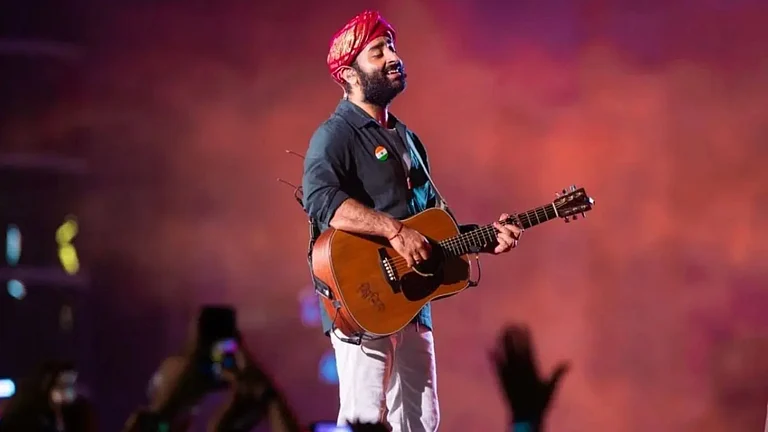

From Aashiqui 2 onward, Arijit Singh brought intimacy and vulnerability into mainstream playback singing, reshaping how Hindi cinema expressed love and heartbreak.

Media-shy and grounded in classical and Bengali music, he chose craft over spectacle, letting the songs, not the star, define his legacy.

Stepping away from playback but not music, Singh signals a creative reset, leaving behind a catalogue that became the emotional grammar of Millennials and Gen Z.

It began, for most people, in a dark cinema hall in 2013. The film was Aashiqui 2. The scene wasn't loud or dramatic. A voice entered softly, almost tentatively, and then stayed. By the time “Tum Hi Ho” reached its final note, something had shifted. Hindi film music had found a new emotional centre.

That voice belonged to Arijit Singh. And for over a decade after that moment, it would come to define what love, loss and longing sounded like for an entire generation.

On January 27, 2026, Singh took to his social media to state that he would no longer take on new playback singing assignments for films. It was a quiet announcement—in keeping with the man himself. No spectacle. No farewell tour. Just an acknowledgement that a chapter had ended. He made it clear that he was not stepping away from music, only from playback singing as Bollywood knows it.

For listeners who grew up with his songs as emotional landmarks, his announcement feels like the end of an era.

Before the Voice Became Ubiquitous

Singh's journey was never about instant stardom. Long before his voice became unavoidable on film soundtracks, he was a music student from Murshidabad in West Bengal, deeply immersed in classical training. Music entered his life early, not as ambition but as routine. He learnt ragas, harmonium and tabla before he learnt the mechanics of fame.

When he appeared on Fame Gurukul in the mid-2000s, it wasn't a launchpad to celebrity. It was a checkpoint. He didn't win. He didn't become a television star. What he did gain was clarity. Singing alone wouldn't sustain him. Music, however, would.

So, he stayed—behind the scenes, assisting composers, programming tracks and singing scratch versions that rarely reached the audience. He worked with some of the biggest names in Hindi film music, quietly absorbing how songs were built, shaped and polished. By the time he sang his first major hits, he wasn't just a singer. He understood the architecture of film music.

The Aashiqui 2 Moment

When Aashiqui 2 was released, Bollywood was already saturated with talent. Sonu Nigam still carried the weight of the 1990s. Shreya Ghoshal and Sunidhi Chauhan were at their peak. KK had given the 2000s their warmth. What Arijit brought wasn't competition. It was intimacy. His voice didn't convey emotions. It inhabited them.

Tum Hi Ho didn’t sound like a declaration. It sounded like a confession overheard. That subtlety changed the texture of mainstream Hindi film music. Suddenly, heartbreak didn’t need theatrics. Vulnerability became the hook.

What followed was a run that few singers in modern Hindi cinema have matched— “Channa Mereya”, “Agar Tum Saath Ho”, “Raabta”, “Phir Le Aaya Dil”, “Muskurane”, “Ae Dil Hai Mushkil”. Each song felt personal, even when played to millions.

For Millennials, his music became the soundtrack of growing up; for Gen Z, it became an inherited emotion—songs discovered on playlists rather than CDs, but felt just as deeply.

A Voice That Refused Celebrity

At a time when singers were becoming brands, Singh remained curiously resistant to celebrity. He avoided interviews, skipped award shows, appeared uncomfortable with public performance offstage. When he sang live, however, the transformation was complete. The shyness dissolved. The voice took over.

This resistance only added to his mystique. He became a presence rather than a personality. People knew his songs better than they knew his face. In an industry obsessed with visibility, that was rare.

Industry whispers occasionally painted him as difficult or unstructured. But directors and composers who understood artistry defended him fiercely. Talent, they argued, does not always fit into assembly lines. Hindi cinema has always made room for such contradictions. Kishore Kumar proved that decades earlier.

The Bengali Parallel

While Bollywood consumed most of the national attention, Singh never abandoned Bengali music. In many ways, that body of work runs parallel to his Hindi career—quieter but just as rich.

In Bengali songs, his classical grounding became more evident. The phrasing lingered. The melodies breathed. Whether singing modern Bengali compositions or Rabindra Sangeet, his voice carried a distinct texture—less cinematic, more intimate.

Over the last decade alone, that quieter Bengali discography has included songs like "Kichu Kichu Kotha", "Tumi Jake Bhalobasho", "Ami Je Ke Tomar", "Tomake Chai", "Egiye De", and "Bojhena Shey Bojhena"—tracks that rarely chased spectacle, but stayed with listeners long after.

He moved between Mumbai and Murshidabad with ease, grounding himself repeatedly in home soil. Jiaganj was not a nostalgic escape; it was a working base. He built studios there, recorded there, lived there. This dual existence shaped his music. Bollywood gave him scale. Bengal gave him stillness.

A Generation Learns to Feel

It's difficult to explain to someone outside this era what Singh means culturally. His songs didn't just accompany moments; they were moments. They taught people how to feel them.

Breakups were processed through “Channa Mereya”. Long-distance relationships lived inside “Samjhawan”. Quiet despair found shape in “Agar Tum Saath Ho”. His music gave emotional permission to grieve softly, to love without bravado.

When KK passed away in 2022, listeners were reminded how deeply voices embed themselves into memory. Zubeen Garg's passing later reinforced the fragility of that lineage. With Singh stepping away from playback, it feels like another door quietly closing—not with tragedy; with time.

Beyond Borders and Genres

Singh has never remained confined to Hindi cinema. He sang across languages, regions and styles. His collaboration with Ed Sheeran on “Sapphire” marked a rare cultural crossover done without novelty. It wasn't about East meets West. It was about two artists meeting on an emotional level.

The collaboration hinted at where his interests were headed—music beyond film narratives. Music that belongs to the singer, not the screenplay.

The Decision to Step Back

In Singh's announcement of retiring from playback singing, the wording matters. He isn't leaving music. He isn't retiring as an artist. He is stepping away from a system that had defined him, perhaps even confined him.

Playback singing demands adaptability—one voice, many characters. Over time, Singh’s voice became so recognisable that it began to dominate films rather than dissolve into them. That, paradoxically, can limit creative freedom.

Stepping away allows him to reset—to compose, produce and collaborate without narrative obligation. Perhaps, it's not withdrawal, but recalibration.

What Remains

Singh leaves behind a catalogue that will age slowly and well. His songs endure not because they are tied to trends, but the act of feeling.

For Millennials, his voice will always carry the weight of first heartbreaks and late-night calls. For Gen Z, it will remain a reference point, a reminder of a time when vulnerability was mainstream.

Playback singing will move on. It always does. New voices will arrive. They always do. But what Singh offered was not just melody. It was emotional literacy.

As he steps away from the film industry's microphone, the silence feels heavy. But it’s not empty. It's full of echoes. Songs that will continue to play—on long drives; on quiet nights; in memory.

The era may be ending. The voice is not.