Summary of this article

Rang De Basanti remains radical for framing patriotism as responsibility rather than hostility, turning its gaze inward to question institutions and civic apathy instead of offering an external enemy.

The film’s unease lies in its refusal to resolve rage or dissent, revealing how political awakening can stall at symbolism rather than sustained action.

Twenty years on, as Bollywood grows safer and nationalism louder, Rang De Basanti stands apart for demanding moral reckoning over emotional release.

It begins with afsos. You might be wondering why this essay opens there and not with the familiar electricity of the radio station speech, nor with raised fists or patriotic chants that once shook cinema halls. It begins with afsos because Rang De Basanti begins with regret long before it arrives at rage. The song does not promise revolution. It mourns the distance between what was fought for and what came after. It sounds like a confession passed down quietly, almost apologetically.

The real regret is that Rang De Basanti is remembered today more for the emotions it stirred than for the uncomfortable questions it asked us to confront.

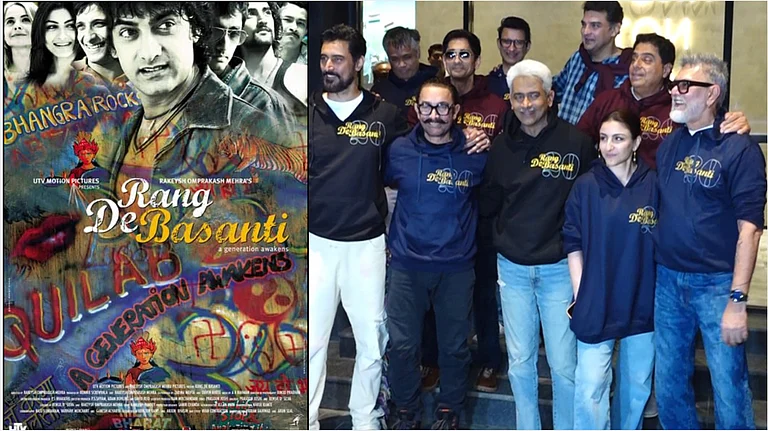

Directed by Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra, the film never announced itself as political. It slipped in disguised as youth, humour, carelessness. It made us comfortable first. By the time it demanded something of us, we were already inside it.

Loving The Country Without An Enemy To Hate

One of the most radical things Rang De Basanti does is refuse to give us an enemy we can conveniently hate. There is no neighbouring country to blame. No border to protect. No faceless villain threatening national pride. The film turns its gaze inward and insists that the real conflict lies within the country's own institutions and within our long-practised indifference toward them.

This is where the film draws a line that feels almost impossible today. It separates patriotism from jingoism with remarkable clarity. Patriotism, in the film's language, is not loud. It does not demand obedience. It survives questioning, discomfort and dissent. Jingoism, by contrast, thrives on spectacle. It needs noise. It needs an enemy to remain alive.

Rang De Basanti chooses the harder path. It argues that loving the country does not require hating another. It requires asking what we have done with the freedom that was paid for in blood. This choice feels revolutionary, especially in a cultural moment where nationalism is often measured by volume rather than conscience.

Patriotism Vs Jingoism: The Line Rang De Basanti Refused To Blur

What Rang De Basanti understands with rare clarity is that patriotism and jingoism are not neighbouring ideas. They are opposites.

Patriotism, as the film frames it, is rooted in memory and responsibility. It demands that citizens remember not just the triumph of freedom, but the cost at which it arrived and the obligations that followed. It allows for anger, grief and dissent because it recognises that love for the country does not weaken when the powers presiding over are questioned. It deepens.

Jingoism, on the other hand, thrives on simplification. It reduces the nation to symbols and slogans, demanding loyalty without introspection. Where patriotism asks what has gone wrong, jingoism insists nothing has.

Rang De Basanti refuses that comfort. By denying the audience a neighbouring country to hate, it dismantles the easiest route to national pride. The film insists that the hardest form of patriotism is not defending the country from outsiders, but holding ourselves accountable from within.

Freedom As A Debt, Not A Trophy

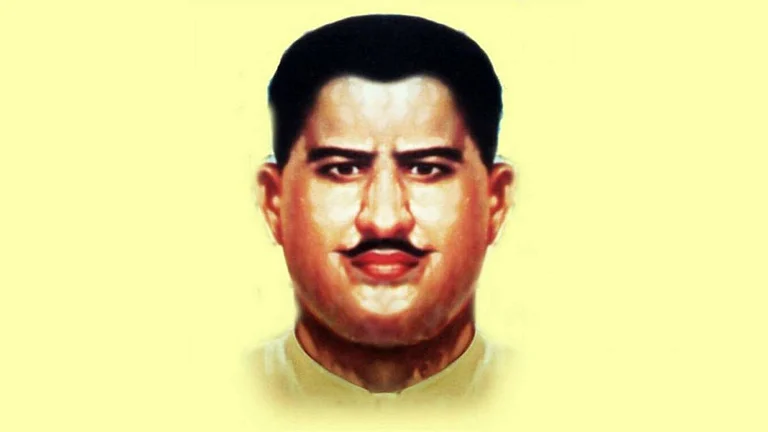

The film's use of freedom fighters is not designed to flatter the present. It is designed to haunt it.

The past in Rang De Basanti is not heroic wallpaper. It is an accusation. The parallel between Bhagat Singh's generation and the present one is not about reclaiming glory. It is about inheritance. Freedom here is not a celebration but a responsibility repeatedly deferred.

What the film asks, without ever saying it outright, is deeply unsettling: what happens to a nation when freedom becomes routine, when sacrifice is remembered only on anniversaries and ideals are reduced to symbols?

This is why the film gives its characters a reason to fight for the country that has nothing to do with dominance or victory. They are fighting not for the India that exists, but for the India their ancestors believed was possible. That belief is fragile. And the film knows it.

Apathy As The Real Antagonist

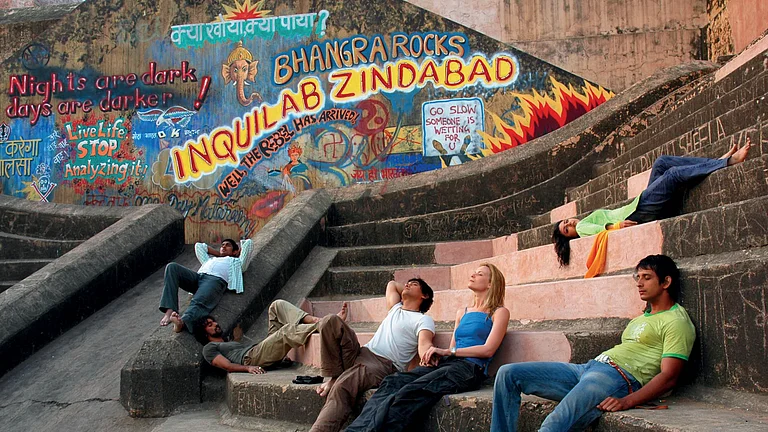

The youth at the centre of Rang De Basanti do not begin as revolutionaries. They begin as spectators—detached; ironically amused by politics; slightly embarrassed by history.

Their political awakening does not arrive through ideology. It arrives through loss. Through the moment when corruption stops being an abstract problem and becomes something personal, irreversible and intimate.

The film understands a truth that remains uncomfortable even now: apathy is not neutral. It is a position. And it is often the most powerful one, because it allows systems to rot quietly. By forcing its characters out of that comfort, the film exposes the cost of disengagement, not as a civic failure, but as a moral one.

Rage Without Reassurance

Rang De Basanti does not offer clean answers about violence and it never pretends to. It neither glorifies rage nor dismisses it. Rage exists in the film as something born out of repeated institutional failure, out of accountability that never arrives. This ambiguity is deliberate. It denies the viewer moral comfort. It refuses to tell us whether the characters are right or wrong. Instead, it asks whether a system that leaves no room for justice leaves any room at all for restraint.

Two decades later, this question feels heavier. In an age where anger is easily mobilised and often redirected outward, the film's inward-facing rage feels dangerous, necessary and unresolved —all at once.

When War Films Became Safer

It is impossible not to contrast Rang De Basanti with many contemporary war films, including recent ones like Ikkis (2025). These films often rely on spectacle, bravery, and external threat. They ask us to feel proud, united, victorious.

What they rarely ask is what responsibility looks like after the war. These films are not without merit, but their politics is safer. They locate heroism at the border, not within broken institutions. They offer emotional release without moral complication.

Rang De Basanti offers no such comfort. There is no victory here, only consequences. No enemy defeated, only a system exposed. That is a far more demanding form of patriotism, and perhaps why it has never truly been replicated.

Nostalgia As An Escape Hatch

Over time, the film has been softened by memory. Its songs are replayed. Its friendships are celebrated. Its dialogues are quoted with affection. What often gets lost is the unease. Nostalgia allows us to revisit Rang De Basanti without re-engaging with its central demand. It lets us remember how deeply it moved us, without asking whether that movement led anywhere. In doing so, the film becomes emotionally potent but politically distant.

From Candle Marches to Quiet Disappearance

In the years following the film's release, its influence spilled out of cinema halls and onto the streets. Candle marches became the language of collective grief and outrage. For a brief moment, public mourning felt political. Silence felt charged. Standing together felt like action.

Rang De Basanti did not invent this impulse, but it gave it a cinematic vocabulary. It taught a generation how to gather, how to grieve, how to be seen together. What it could not teach, and perhaps never claimed to, was how to sustain that energy once the candles burned out.

Over time, the marches became ritualistic, predictable, symbolic. Outrage learned how to assemble and disperse without consequence. What began as a disruption slowly became a performance, emotionally sincere but structurally harmless. This is not the film’s failure. It is an unnerving afterlife of its success.

The Question That Still Remains

At twenty, the film does not feel old. It feels unresolved. It asks whether we learned how to act or only how to feel together. Whether freedom became a responsibility or merely an inheritance, we stopped questioning whether loving the country still means holding it accountable, or simply defending it from criticism.

The film never promised answers; it promised an unsettling. And that is why it still begins with afsos. Because the regret was never confined to the screen. It was always meant to belong to us.