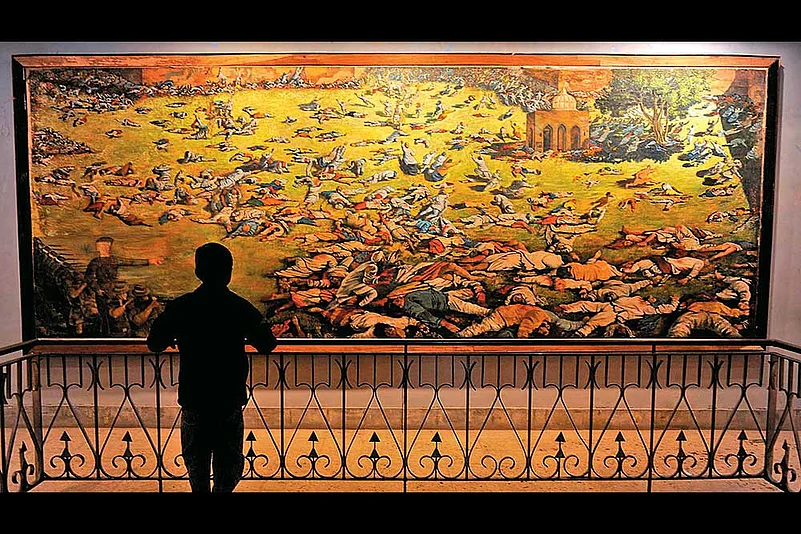

The Lok Sabha recently passed a bill to amend the Jallianwala Bagh National Memorial Act, 1951, which had been introduced to provide for the “erection and management of a national memorial to perpetuate the memory of those killed or wounded on the 13th day of April 1919, in Jallianwala Bagh.” One of the main proposals of the Jallianwala Bagh National Memorial (Amendment) Bill, 2019, seeks to remove the Congress president as a permanent member of the memorial trust. The Lok Sabha passed it amidst a walkout by the Congress. The conflict over the removal of the Congress president continues in the Rajya Sabha.

There should not be representatives of any political party in the memorial. Instead, it is time to highlight victims’ voices. Previous governments have rarely acknowledged them and they continue to remain unrecognised or forgotten. None of them, especially the ones who lost their family members, are represented as trustees. Shockingly, even the present bill does not take this injustice into account.

History’s truths are relevant here. The erstwhile Indian National Congress has had an ambiguous relationship with the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. Indeed, Gandhi’s anti-Rowlatt satyagraha escalated before April 13, 1919. But the crowd in Jallianwala was a mixed lot—some had come for the cattle fair and to celebrate Baisakhi. It’s doubtful whether it was a political meeting; there weren’t any well-known Congress leaders present. Hans Raj, a local Congress representative, later proved to be an agent provocateur and a villain of the massacre.

Those attacked in the garden were common people, mostly unaware of the larger political situation. They were abandoned by prominent leaders and left to their fate on that day. Col Reginald Dyer’s vengeful act was influenced by a sinister determination to teach the people of Amritsar a lesson. Gandhi assumed centrestage only after the carnage. His astute leadership brought the Jallianwala Bagh tragedy into the grand saga of Indian nationalism and shaped the contours of a robust anti-colonial struggle.

It’s important to recognise that the Congress itself has undergone a major transformation. Under the Raj, it was a popular movement but after 1947, it became a party strongly tied to vote-bank politics. In its initial years, the trustees of the Jallianwala Bagh National Memorial included luminaries like Jawaharlal Nehru, Maulana Azad and Saifuddin Kitchlew who were intimately associated with the freedom struggle. Today, the situation is different as the Congress leadership has no mass support.

The fact that the prime minister will continue to lead the trust deserves appreciation. I hope that the sanctity of the memorial and the victims’ memories are given due homage. The concerned citizens of Amritsar are demanding that the dignity of the dead be restored. To capture the lost histories of pre-Partition Punjab is not easy. Many families of victims and survivors left for Pakistan after 1947. Others moved to different states of the country. Besides, some outstanding local leaders have been blotted out from the pages of history. Saifuddin Kitchlew is one of them. Isn’t it time to trace such erased narratives?

As chairman of the trust, the prime minister must ensure that an objective and inclusive history of Jallianwala Bagh is sustained through the memorial. The politics of the present and past can mar the local narratives of the massacre. Let’s not forget that different castes and communities were present in the garden and that brave women struggled to recover the bodies of their husbands and sons. Memorials ought not be turned into battlefields for political and ideological interests. Instead, they should convey the multi-layered, divergent meanings that people attach to these sites. Therefore, the present debate over the bill rings hollow.

Future generations can learn from the Jallianwala Bagh National Memorial if it catalogues the stories of the dead and survivors, and maps the horrors of imperial violence. This is to neither diminish the Congress’s connection with the event nor to exaggeratedly glorify its sacrifice for the nation. It is to learn solemn lessons from the massacre and respect the memorial’s sanctity as a monument that was erected to commemorate the deaths of hundreds of innocent people in Amritsar.

(The writer teaches history at Jawaharlal Nehru University)