Last week, the Supreme Court passed its final verdict in the much-publicised case of “medical negligence” that led to the death of my wife Anuradha, who was a child psychologist in the United States. After a legal battle that ran 15 years, the court unequivocally held four senior Calcutta doctors and the AMRI Hospital responsible for Anuradha’s death and awarded a compensation of around Rs 11 crore (including interest), by far the highest awarded in Indian medico-legal history.

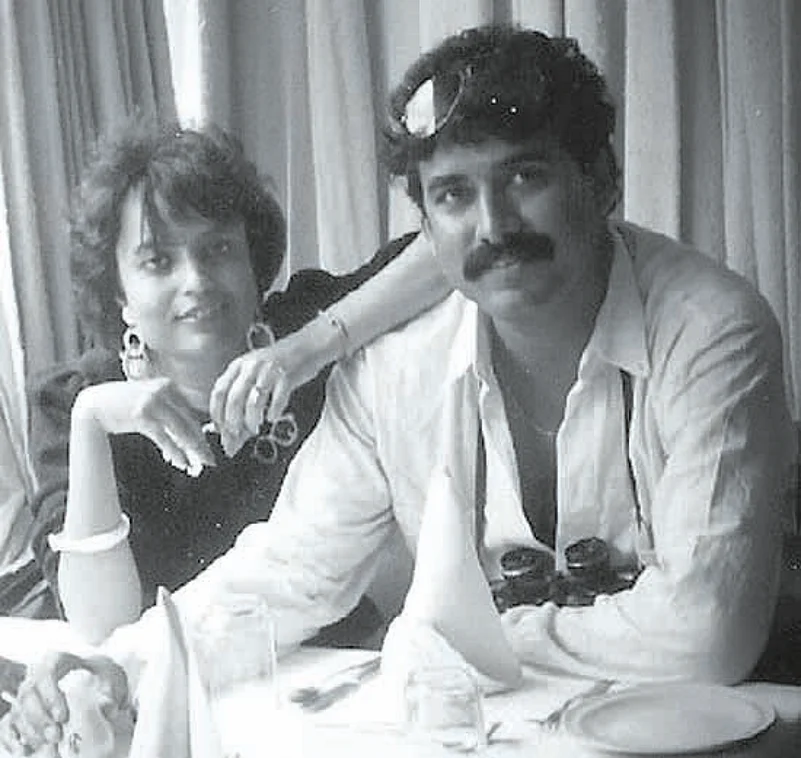

Anuradha died while on a short social visit to India in 1998, succumbing to the most unscientific and reckless treatment. She was only 36. As new immigrants to the US, we were on the threshold of our professio–nal careers and the American dream when this happened. I was in a state of shock, having watched her die from what had been diagnosed as a simple “drug allergy”.

Nevertheless, I embarked on a seemingly impossible legal battle to seek justice not only for my departed wife, but also for the thousands of other Anuradhas who are victims of reckless therapy in hospitals and nursing homes across India every day. My friends and family tried to dissuade me: they believed that in India, it would be impossible to bring influential doctors to book. But I believed my wife’s death brought me a bigger purpose in life. Having fought the case to its end, I see the Supreme Court’s verdict as a vindication, a stamp of approval of my belief that Anuradha died because of the ignorance and arrogance of some Indian doctors. Our victory is a small beginning towards checking—and eventually trying to end—rampant medical negligence in India. There’s a long way to go before innocent patients are spared death due to the irresponsible attitude of some of our healers and the endless greed of some of the hospitals and nursing homes mushrooming across India.

While ordinary people in India see in the judgement a glimmer of hope that doctors have finally received a stern message against negligence in treatment, leaders of the Indian Medical Association (IMA) and other medical groups are crying foul. Some of them are spreading the idea that the judgement will encourage “defensive” medical practice: only to be doubly sure and safe and avoid litigation, doctors would start recommending a wide range of expensive investigations that could be done without. But may I ask if anyone really believes that, so far, doctors have been restraining themselves from prescribing expensive (and probably unnecessary) tests to save patients’ money? It’s time doctors realised that public trust in healers has plummeted to a record low. The reasons are not hard to see: there are no checks and balances for doctors. The Medical Council, India’s central regulatory authority for doctors, is both inept and collusive. Private hospitals and nursing homes are reaping enormous profits while working without (or with little) oversight; doctors themselves are in a race to amass as much wealth as possible and they try to achieve this by squeezing in as many patients as possible into their practice hours. Both hospitals and doctors go scrambling about for wealth, putting patients at risk and with no fear of being questioned.

This is abetted by an unwritten omerta, or code of silence, by which doctors in India refuse to speak up against delinquents from the profession or make adverse comments on cases in which patients are clearly victims of negligence or out-and-out professional error. Thus it’s virtually impossible for the common man to take legal recourse and seek redress for medical negligence.

If excessive litigation had led to a fall in the standards of medical care, as suggested by the IMA, then the quality of healthcare in developed countries would have collapsed a long time back. While lawsuits aren’t the most desirable way of cleansing the rot in the Indian healthcare system, people will have little choice but to go to the judiciary until a degree of transparency is established, until a regulatory system that works is in place and until doctors start giving evidence, unemotionally and as professionals, in cases of negligence, errors of judgement or sheer ignorance that lead to patients dying or suffering damage. Or else, in sheer hopelessness and anger, as it often happens in India, they may end up taking the law into their own hands, beating up doctors and vandalising hospitals after losing their loved ones. That, of course, will never solve the problem of medical negligence.

In the course of 15 long years of litigation, I never once alleged that the doctors did not advise or perform the tests that were necessary. The burden of my argument was this: they used the wrong drugs, prescribed excessive doses and did not provide minimal supportive therapy, resulting eventually in Anuradha’s death. Additional tests could not have prevented her death: what caused the death were these acts of omission and commission by the Calcutta doctors and AMRI Hospital. It is these critical factors that the 210-page judgement brought to light, sending a strong message that reckless, unscientific practice will not be tolerated. In fact, as a deterrent, the judges have issued a stern warning against doctors “who do not take their responsibilities (of treating patients) seriously”. The court also chastised them for unethical behaviour: they had at various points tried to shift the blame on to one another.

I’d also like to point out that Indian doctors need not panic that payouts as large as `11 crore for a single medical mistake will leave them bankrupt. The court has clearly suggested that, while errant doctors must pay for their negligence, the bulk of the compensation for the victim must come from the hospital, which makes the maximum profits from patients. Also, the compensation rose to `11 crore in this case because Anuradha’s prospective loss of income was calculated based on her income in the US. Patients who live in India will have the compensation calculated based on potential earnings in this country.

I have reasons to believe that healthcare issues highlighted in Anuradha’s case judgement are common problems in Indian hospitals and result in numerous deaths and permanent injuries daily. Anuradha died because of the heavy overdose of a rarely used steroid (Depomedrol) that causes serious side-effects like immuno-suppression. The doctors and AMRI Hospital were not willing to discuss the use of the drug even as Anuradha went from bad to worse. Doctors in India are generally reluctant to discuss the drugs they use, the side-effects, the treatment protocol with the family or even the patient. This despite the fact that they are legally and morally bound to provide a complete picture to the patient. Doctors are also duty-bound to obtain “informed consent” from the patient or his family about any risks associated with the treatment. Unfortunately, these fundamental rules exist only on paper and are flouted with impunity. Fifteen years after I lost the most precious gift that I ever had in my life, my battle for justice for my departed wife may have come to an end. But my struggle to stop the pervasive medical negligence in Indian hospitals has just begun and will continue through People for Better Treatment (PBT), an organisation I have established to help victims of medical negligence. It’s my way of ensuring that other Anuradhas may get a chance enjoy the gift of life.

(Saha is adjunct professor and private consultant on HIV-AIDS in Columbus, Ohio, and president of People for Better Treatment, set up to fight for patients’ rights.)