The Sino-Indian conflict of 1962 over the disputed boundary was a short war, lasting barely four weeks. Yet, its impact on Indian politics, particularly on the Indian Left, has been immense. The “China question” was not only instrumental in splitting the undivided Communist Party. In subsequent years China and its ideologues kept popping up at regular intervals, splitting the Left movement further and allowing wide-ranging groups, from Naxalites to the Northeast insurgents and the Maoists, to draw sustenance from them.

The furrows on veteran CPI leader A.B. Bardhan’s forehead deepen while discussing the “China question” that split the Communist Party of India in the aftermath of the war. The differences amongst leaders, brewing over the past years, came to a head after India’s humiliating defeat.

“China cannot be the aggressor,” Jyoti Basu had proclaimed at a public rally in Calcutta soon after the war. Many of his party colleagues agreed, squarely blaming the Indian leadership’s intransigence on the boundary dispute and its “provocation” for the war. But there were many others, dubbed as “rightists” within the party fold, who strongly disagreed.

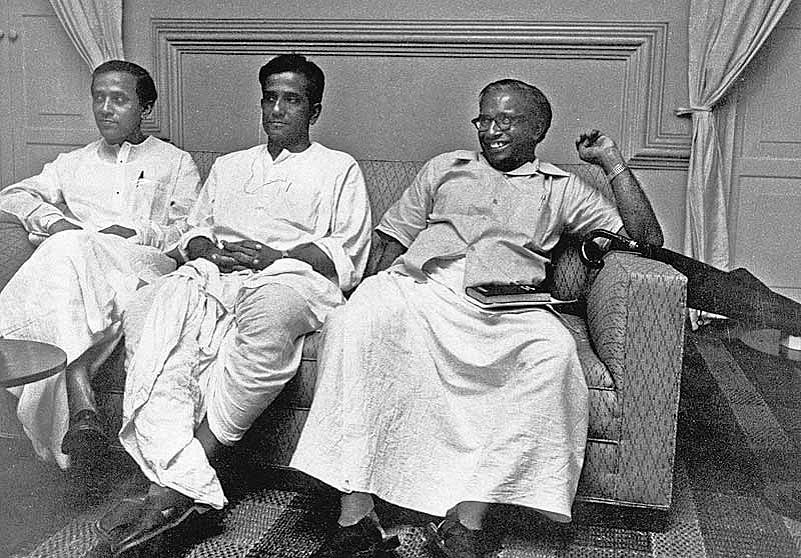

“The 1962 war may have acted as a catalyst but was not the real reason for the split,” says Bardhan. The split came after two years, in 1964, with the breakaway group calling themselves the Communist Party of India (Marxist). But in the intervening period, when thousands of ethnic Chinese citizens were interned in camps, “pro-Chinese” leaders like Jyoti Basu, E.M.S. Namboodiripad, Sundarayyah, Basavapunnaiah and Benoy Chowdhury were put behind bars by the government.

Bardhan, however, claims discontent in the party was not only directed against the “pro-Chinese” faction, but also against a large number of others. Working as a trade unionist in Nagpur, he too was arrested. “I spent 14 months in jail and for a brief period shared a cell with E.M.S. Namboodiripad.”

What then were the real reasons for the split? There are no clear answers; there are different versions, ranging from international developments to petty party politics, that explain the decisive rift amongst the former comrades.

According to some veterans of the Communist movement, the differences within the party fold stemmed from developments in the Soviet Union after Joseph Stalin’s death in 1953. Cold War politics and the US’s attempt to encircle the USSR through a series of pacts like NATO, CEATO and SENTO were serious cause for concern for many leaders in the Communist party. Jawaharlal Nehru’s stock among these leaders shot up when he refused to join these pacts despite repeated requests from the US. He was, therefore, seen as a champion of “anti-imperialism.” And as an extension of this argument, the Indian leadership became “national bourgeoisie” with whom the Communists could align in their fight against US-led imperialism.

The “pro-Chinese” leaders, many of whom were products of the peasants’ movements, regarded Mao’s China as the model to launch a “people’s democratic revolution” in India. For them, Nehru was a “comprador bourgeois” who made compromises to remain in power and with whom they could not align in any forseeable way to launch their struggle and transform India in the model of China.

“We never believed China would like to annex land from our country,” says Tushar Kanti Roy, a veteran of the “pro-Chinese faction” in the party. Like other pro-China members of the party, Roy joined the CPI(M), but was expelled in the mid-1980s because of serious political differences with the leadership.

When the Sino-Indian border dispute erupted in a war, the fractiousness sharpened and subsequently led to the split. But looking back five decades later, many veterans acknowledge that not all the differences were “ideology-driven”; “petty politics” had a major role and stemmed from personal likes and dislikes.

“Some leaders who later proclaimed themselves as ‘pro-Chinese’ had often criticised Mao Tse-tung and even refused to accept him as a Communist,” says Pallab Sengupta of the CPI. He adds, “Reservations about S.A. Dange’s leadership was also a key driver for the split.”

Irrespective of what the real reasons were, “revisionist” was a popular word that entered the parlance of those involved in the Indian Communist movement, and it was used often to run down leaders from the other side.

“It is ironical that the CPI(M), which dubbed us revisionists, fell prey to the same accusation in 1967 by the Naxalites,” Bardhan says with a smile.

But if Naxalite leaders like Charu Majumdar and Kanu Sanyal hurled those charges against their erstwhile party colleagues before floating their own party, the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist), in 1969, they could not prevent the party from further splitting in different factions, mostly in tandem with the upheavals in the Chinese Communist Party. Two years earlier, the Radio Peking announcement of “a peal of spring thunder over India”, to encourage the peasants of Darjeeling, had electrified Naxalite leaders in Bengal and elsewhere in the country. Some of them even managed to travel to China and meet CPC leaders, where they were egged on to continue their struggle against the Indian state.

Meanwhile, Northeast insurgent groups, be it the Nagas, the Mizos or the Manipuris, all turned towards China—as the real power that succeeded in humiliating India—for help in their own movements to create independent states. Many of them undertook the hard trek to China through Burma (Myanmar), where they received arms training and weapons from Chinese military officials to fight the Indian security forces.

But all that has now stopped, at least officially, with China denying any involvement with insurgent groups in India. Senior CPC leaders told Outlook in Beijing recently, “There was a time when China encouraged various groups to carry out their struggles. But now we deal only with those parties that are considered legitimate in their respective countries.”

True, much of the support to the Naxalites or the Northeast insurgents came at the height of Mao’s Cultural Revolution in the 1960s when China wanted to spread world revolution. But that ended with Mao, and the death of his ‘revolutionary’ tenets. Today, the Chinese emphasise the strengthening of economic ties with India and others. Talk of ‘Maoist’ groups in India, and they are dismissed out of hand.

“We want to build a harmonious society in China and for that it is essential for us to have a peaceful neighbourhood,” says a senior CPC leader.

Chinese foreign ministry spokesman, Hong Lei, agrees. While acknowledging the 1962 war, Hong says, “Yes, this is a period in our relations which is part of our history”. However, he quickly adds, “But we are happy that no bullets have been fired since. The borders have remained peaceful and it is important for us to keep them peaceful.”

Material gains have changed China and effectively weaned it away from actively seeking to export its brand of armed revolution. But the pull of a strong China, playing a more significant role in world politics, will never wane. Its influence isn’t spent yet; there will be Leftist groups in the subcontinent that will turn to China for hope and sustenance.