The ratcheting up of the pitch for a Uniform Civil Code (UCC), particularly during the time of elections, begets an extremely polarising form of political mobilisation. In television debates, frenzied panellists discussing the UCC are either for it or not. Common citizens, too, are seen articulating their positions in either/or propositions. Most of us miss out, while debating the UCC, the possibilities of a constructivist approach to gender justice and the social reforms embedded in it. We get entangled into its rhetoric of the codes of uniformity and conformity and less into its foundational signifiers of plurality, equality and civility. The whole debate of the UCC is played out on a single axis of uniformity leading to minority-majority communalism. The real issue of gender-just laws cutting across religious and caste lines, which is quintessentially a feminist movement issue, is ‘subalternated.’

A Historical-Constitutional Framework

The UCC is predicated on civil reforms which are inextricably linked to socio-economic reforms. During the Indian Independence struggle, as Kumari Jayawardena notes in Feminism and Nationalism in The Third World, feminists got involved in issues related to nationalism, national identity and critiques of British imperialism and western identity, and shied away from issues related to patriarchy in Hindu and Islamic laws and caste systems. Between 1917-27, despite the call of three major women’s organisations for socio-legal reforms—the Women’s Indian Association (WIA), All India Women’s Conference (AIWC) and the National Council for Women in India (NCWI)—religious traditions and family life pertaining to inheritance, maintenance, divorce, custody, guardianship of children, polygamy, purdah, and female education were least disrupted by the socio-religious reform movements prior to Independence.

The British intended to bring uniform laws for both civil and criminal jurisprudence, but in the civil arena, they codified the laws by leaving out ‘private’ areas, as it wasn’t a politically viable option for them. They did manage to legislate, however, a few progressive laws, such as the Sati Regulation Act (1829), Widow Remarriage Act (1856), Age of Consent Bill (1891), Child Marriage Act (1929) and so on. Personal laws, so to say, ensconced in the private sphere, were essentially customary community laws deriving their essence from religious texts, and any reform in them, the British thought, might distress the socio-religious fabric. Patriarchy within the private sphere that manifested in the form of male privileges, subordination of women within family systems and gender-based power imbalance in the family, all remained more or less intact.

The Shah Bano case was a turning point in the debate on the UCC and in the rise of religious communalism in politics.

In the Constituent Assembly, Renuka Ray had insisted on having clear provisions in the fundamental rights for the prohibition of any discriminatory practices in marriage and inheritance laws, but the debates veered around the generic ‘equality’ clause. Members believed, like the British, that any intervention in personal law would affect religious practices and traditions, and hence would appear as a ‘tyranny of the majority’. In place of equal rights for women, particularly in the private sphere, the identities and rights of religious communities were debated, and thereupon the idea of a UCC was placed in the Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) chapter of the Constitution. Article 44 in the DPSP ensures that ‘the State shall endeavour to secure for the citizens a uniform civil code throughout the territory of India’. Since the matters of personal law and civil procedure are in the concurrent list, the onus of legislating the UCC rests with both the states and the centre. The legislative powers assigned to the Union, in our federal scheme, however, have primacy over the powers given to the states. It is important to note that, though the DPSP exist in the form of non-enforceable socio-economic guarantees, the Supreme Court has invoked them quite often, along with the right to equality before law and the right to protection of life and personal liberty.

The Hindu Code Bill And The Shah Bano Case

The Constituent Assembly, acting as a provisional Parliament, had debated the government’s proposal of Hindu personal laws and prepared to have some sort of common civil code. The Hindu Code Bill, as it came to be known, faced stiff opposition from its orthodox and conservative members. They argued that the Bill, apart from being harmful to Hindu family systems, will degrade the deified position of women and therefore disrupt Hindu social life. They also alleged that the demand for a uniform Hindu code seeking gender-just laws was coming from ‘elitist’ and ‘western’ women who do not represent Indian women, and therefore, Indian women would relinquish these rights, if granted, in favour of duties towards their own family. Clearly, the conservatives and patriarchs were not ready to yield to equal rights for men and women, in spite of agreeing to the fundamental right to equality. The Bill, though passed in 1956, was quite different when compared to the original draft, with the rights of women getting diluted to a large extent. The State made no effort to make this law workable, or to make the personal laws egalitarian by undertaking social reforms as envisaged in Article 25(2) of the Constitution.

The Shah Bano case (1985) was not only a turning point in the debate on the UCC but also in the rise of religious communalism in Indian politics. The five-member Bench, led by Justice Y V Chandrachud, entered into the realm of Muslim personal law and upheld Shah Bano’s—a divorced woman seeking maintenance from her husband under Section 125 of the CrPC—right to maintenance under both Muslim personal law and Section 125 of CrPC., and further asserted that Section 125 transcended personal law. It also urged the government to frame a common civil code and end the unjust treatment meted out to women of different religions. Soon after, conservative Muslims, ulemas, feminists and liberals together shrieked that the judgment was bringing the issues of religion and personal laws into a secular criminal law. Feminist Madhu Kishwar had remarked, “By singling out Muslim men and Islam in this way, Justice Chandrachud converts what is essentially a women’s rights issue into an occasion for a gratuitous attack upon the community”. Interestingly, Hindu communalists gleefully supported the judgment and blamed Muslims as ‘anti-national’ and ‘barbaric’. In 1986, Parliament passed the Muslim Women’s Bill and altered the judgment so that divorced Muslim women get their maintenance not from their husbands but from the Waqf Board. Massive demonstrations were held thereafter by liberal, left and feminist groups against the regressive and violative aspects of gender justice and the demonstrations held by right-wing groups were more for subordinating the minority identities to majoritarianism than to gender justice.

In both cases (the Hindu Code Bill and the Shah Bano judgement), the efforts to legislate a uniform code for gender-just laws were undermined by conservative and patriarchal groups citing threats to religion and culture. On the contrary, feminists, as early as the 1970s, as evidenced by the report of the Committee on Status of Women in India and the Muslim Women’s Conference held in Pune—had kept up their demand for a UCC.

Conformity In Uniformity

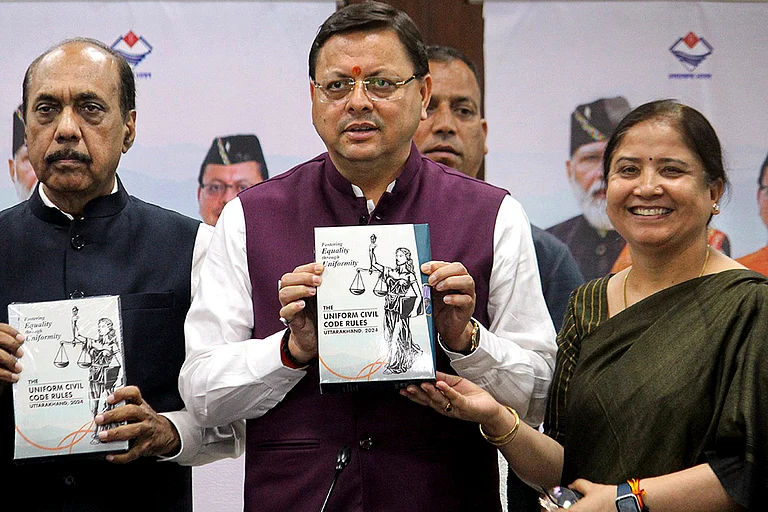

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), a key player in pushing for an immediate common civil code, views the UCC as an instrument of mitigating the ‘differences’ between communities (Hindu, Muslims, Sikhs, Christians, Scheduled Castes and Tribes) by yielding to one common code or law for governance. The party believes that since Hindu laws have been reformed and a uniformity within the community has been achieved, it is Muslim personal law that needs a change. Rather than uniformity, the party seeks conformity under the umbrage of ‘one nation, one law’ and demands for the UCC to be predicated on Hindu laws. In this high pitch and cacophony for the UCC, the unequal laws in matters pertaining to marriage, inheritance, guardianship, adoption are completely ignored in Hindu personal law.

The UCC must give primacy to secular laws over personal laws, particularly in cases of conflict between laws covering areas of civic exchange.

Another argument the BJP makes in pushing for the UCC is that a single law will bolster national integration and a deified nation, quite like the ‘reified religious identity’ constructed by the British. The danger, however, in such a proposition is that the construction of nation, national identity, and religious communities is wrought largely in the ‘public sphere’, where communal violence transforms uniformity into conformity for a majoritarian civil code. National integration is missed, in any case, despite having uniform laws in many areas. How could the UCC be different and bring out national integration? National integration is, in fact, a matter of equality and inclusivity, and not conformity and exclusivity.

The Way Out

So what should be done about the UCC? Should it be left to political parties to stoke communal passion and jingoism during election season? Should it remain a potent instrument of religious polarisation and of provocation, kindling fear and hate between communities?

The UCC is not a bad idea as such. But in a pluri-national and multi-religious nation like India, it may not be the best available option. For the UCC to work, it must be directed towards attaining gender-just laws within religious and cultural communities, a sort of stirring the idea of ‘reforms from within’. The laws must have the potential to override personal laws and provisions to ensure the State’s protection of safety and dignity of minorities. Communities may be urged to rationalise their personal laws in the backdrop of constitutional values of equity, justice and good conscience. The UCC must give primacy to secular laws over personal laws, particularly in cases of conflict between different sets of laws covering specific areas of civic exchange. A comprehensive gender-just package of legislation, even in the areas where laws do not exist, is needed. If these do not form the essential part of the bucket-list of the UCC, then it must be dropped as any bad idea should be.

(Views expressed are personal)

(This appeared in the print on 11 June 2023 as 'Uniformity Or Conformity')

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Tanvir Aeijaz teaches public policy at Delhi University