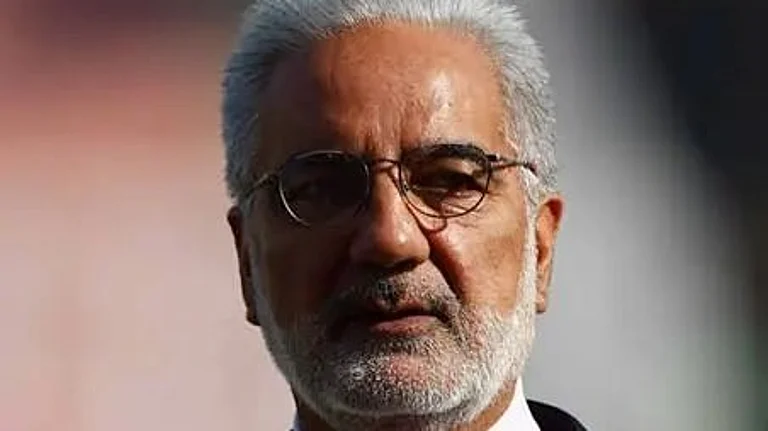

Saira Shah Halim is an activist, educator and politician. Raised in various parts of India and the Gulf due to her father’s army career, she travelled extensively and became familiar with a variety of cultural and social environments. After a 17-year-long stint in the corporate world, Halim gravitated towards social work and activism. She was closely associated with the farmers’ movement, the anti-Citizenship Amendment Act and the anti-National Register of Citizens protests. Halim made her political debut in March 2022, contesting on a Communist Party of India (Marxist) ticket in the Ballygunge Assembly by-poll in West Bengal.

Though she lost the election, Halim managed to increase the CPI(M)'s vote share from five per cent to 30 per cent—an unexpected turnaround for the party. Niece of veteran actor Naseeruddin Shah, Halim is part of several platforms promoting secularism, democratic values, gender equality and diversity. She spoke to Vineetha Mokkil about Comrades and Comebacks: The Battle of the Left to Win the Indian Mind, which aims to bring the Left to all those who are in search of alternatives to an unjust world. Excerpts:

Why did you decide to write Comrades and Comebacks at a time when there is a great deal of speculation about the relevance of the Left in contemporary politics?

I felt this was the right moment to write my book because the Left is being written off by many, and yet, beneath the surface, there is a restlessness and hunger for alternatives. I wanted to document both the setbacks and the possibilities of renewal of the Left. My intended readers are young Indians who may have only seen and encountered caricatures of the Left—through memes or casual stereotypes—and older readers who may have grown disillusioned but still care about justice and equity. That’s why the language of Comrades and Comebacks is deliberately accessible and story-driven: to connect across generations.

There are certain misperceptions in the public imagination about the Left and Leftists. Are you trying to clear some of these up? To what extent can books actually change mindsets?

One of my aims was to dismantle clichés—like the ‘jhola, kurta and slogans’ image—and to show that Leftists are ordinary people grappling with extraordinary challenges. Stalin’s excesses are often weaponised to dismiss the Left entirely, but India’s Left has its own indigenous journey. Literature cannot single-handedly overturn prejudice, but it can humanise political ideas and invite people to look again with fresher eyes.

You begin the book with a historical overview. Why was it important to place Left politics in world history before delving into the role of the Left in India?

The Left in India has always been connected to global movements—whether it is anti-colonial struggles, the fight against fascism, or solidarity with Palestine. By situating Indian Left politics within world history, I wanted to show both the inspirations and the divergences. It also helps readers understand that the challenges and reinventions of the Left are global, not just Indian.

You contested the Ballygunge Assembly elections in 2022 as a CPI(M) candidate. Why did you decide to enter electoral politics? How challenging was that campaign for you?

After years in media, training, communication, and activism, stepping into electoral politics felt like the next logical move. It wasn’t easy—being a woman candidate, challenging entrenched stereotypes, and fighting in a high-profile constituency was daunting. It is certainly not for the faint-hearted. The trolling can be vicious; sexist and communal, both, but it also showed me the warmth of people’s engagement and their yearning for cleaner, people-centred politics. I wanted to prove that politics can be principled and humane.

In post-Independence times, Leftist ideas were reflected in popular culture—Bollywood films, theatre, music. Popular culture is an influential medium the Left should try to utilise more, isn’t it?

Absolutely. In the decades after Independence, the Left infused films, songs, and theatre with ideas of solidarity and justice. Popular culture shapes emotions before it shapes votes. The Left must reclaim that terrain—through cinema, music, digital platforms, even memes. If we want to reach Gen Z, it won’t be through pamphlets alone, but through culture that inspires and resonates.

You do cover the Left’s decline in former strongholds like West Bengal, Tripura, and to some extent Kerala, in the book. But have you glossed over some of the Left's mistakes in understanding the electorate’s concerns?

It’s true that mistakes were made—whether misreading aspirations of the youth, being slow to address caste and gender realities, or underestimating the power of consumerist culture. I didn’t want to dwell excessively on self-criticism, but neither did I want to brush it under the carpet. The point of my book is to highlight lessons learnt and to focus on renewal, not just regrets.

You write, “If the Left embraces introspection and innovation, it can inspire a new generation”. What concrete steps are being taken to speak to the new generation?

There are exciting experiments—student movements in campuses, grassroots initiatives linking climate justice with workers’ rights, and women’s collectives that merge feminist and socialist politics. Internationally, there are figures like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the United States, or Zohran Mamdani as the new poster boy of Left politics who are exciting to watch. Mamdani is cool and the young and not-so-young have really taken a liking to him, and I am hoping he becomes Mayor of New York soon. [Former Labour leader, now an independent] Jeremy Corbyn, during his peak in the United Kingdom, connected well with the youth. In India, younger leaders are emerging who speak the language of equity and sustainability while being digitally savvy. These are the bridges to tomorrow.

Are you hopeful about the Indian Left’s comeback in electoral politics?

Yes, I am cautiously optimistic. The comeback may not be immediate or sweeping, but new cracks are appearing in the edifice of unrestrained capitalism—climate collapse, inequality, alienation. A post-capitalist future, to me, is not a utopia but a pragmatic rebalancing: where resources are shared more fairly, work is dignified, and communities matter as much as corporations. The Left can play a vital role if it stays rooted in people’s struggles while being unafraid of innovation.

(Vineetha Mokkil is Associate Editor, Outlook. She is an alumna of New York University and the author of the book 'A Happy Place and Other Stories)