Spiti has become India’s first cold desert biosphere reserve under UNESCO’s prestigious Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme.

There are approximately 700 biosphere reserves worldwide.

The reserve is structured into three zones: a 2,665 sq. km core zone, a 3,977 sq. km buffer zone, and a 1,128 sq. km transition zone.

Spiti, Himachal Pradesh’s remote high-altitude valley, known for its unique culture, rugged terrain, pristine glaciers, landscapes, and ancient Buddhist monasteries, has carved its name into the prestigious global conservation network.

Also called the land of mysteries, Spiti has become India’s first cold desert biosphere reserve under UNESCO’s prestigious Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme, a recognition that honours its fragile ecology, climate, topography, and indigenous traditions.

Located in the northeastern part of northern India, at an elevation between 12,470 and 15,050 feet, Spiti is part of the Lahaul-Spiti district, a strategic area bordering China.

There are approximately 700 biosphere reserves worldwide, and Spiti's inclusion in this network has brought joy to a team of Himachal Pradesh Forest officers and ecologists, who have been working diligently for several years to see the area evolve into a model of sustainable conservation and development.

"From presenting the idea at the Chennai UNESCO MAB conference in 2023 to the inclusion of Cold Desert Biosphere Reserve (CDBR) in the UNESCO MAB network, it’s been a heck of a journey!" A senior forest officer expressed his eternal gratitude for this achievement.

Spiti spans an area of nearly 7,770 square kilometres, with Komic village, perched at 15,050 feet, recognised as the world’s highest inhabited settlement.

The recognition was formally conferred at the 37th International Coordinating Council (MAB-ICC) meeting, held in Hangzhou, China, from September 26 to 28, 2025. With this inclusion, India now has 13 Biosphere Reserves in the UNESCO World Network of Biosphere Reserves.

Chief Minister Sukhwinder Singh Sukhu, who has since returned from his visit to the UK, said Spiti will gain immensely from its new designation. “Its unique ecology, climate, culture and heritage, as well as the commitment of local communities who have lived in harmony with nature for generations, will get worldwide recognition.”

He said, “The government is committed to protecting and conserving Himachal Pradesh’s rich natural and cultural heritage and fragile ecology in the era of climate change, while ensuring harmony between developmental activities and nature.”

The details released by the government add that the reserve is structured into three zones: a 2,665 sq. km core zone, a 3,977 sq. km buffer zone, and a 1,128 sq. km transition zone.

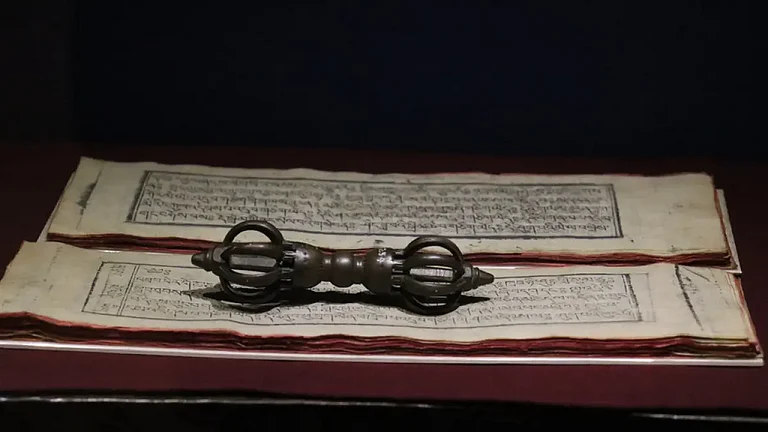

It encompasses Pin Valley National Park, Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary, Chandratal Wetland, and the Sarchu Plains, representing a unique cold desert ecosystem characterised by its extreme climate, topography, and fragile soils. The region is ecologically rich, harbouring 655 herbs, 41 shrubs, and 17 tree species, including 14 endemic and 47 medicinal plants central to the Sowa Rigpa/Amchi healing tradition.

Spiti’s wildlife includes 17 mammal species and 119 bird species, with the snow leopard as a flagship species. Other notable species include the Tibetan wolf, red fox, ibex, blue sheep, Himalayan snowcock, golden eagle, and bearded vulture. With more than 800 blue sheep, Spiti Valley alone provides a strong prey base for large carnivores.

Amitabh Gautam, PCCF (Wildlife), said, “This recognition firmly places Himachal’s cold deserts on the global conservation map. It will enhance international research collaboration, promote responsible ecotourism to support local livelihoods, and strengthen India’s efforts to build climate resilience in the fragile Himalayan ecosystems.”

Samuel Bourne, an early pioneer of photography in the Himalayas, first photographed Spiti in the 1860s. In 1933, Eugenio Ghersi, a member of the Italian Tibetologist Giuseppe Tucci's expedition to Spiti and Western Tibet, filmed Spiti for the first time. The narration of this 46-minute-long video is in Italian.

Says Suresh Attri, ecologist and joint member secretary of the HP Council for Science, Technology, and Environment, “It is indeed a very good decision. Although it is delayed, it remains important nonetheless.

"The biosphere reserve aims to conserve all forms of life in their natural environment, along with their supporting systems, so that it can serve as a reference for monitoring and evaluating changes in natural ecosystems." The Himachal Himalayas are already under tremendous pressure due to the changing climate.”