Thirty years ago, when the West was yet to discover fully the potency and potential of new information technology to package and sell politicians, an old-school British Conservative Party strategist, Norman Tebbit, had sceptically noted that the public “can smell a dead rat even when it is wrapped in red roses”. Narendra Modi and his NRI promoters have disproved the Tebbit formulation by carving out an impressive victory. The Modi hat-trick comes despite a marked disquiet among significant sections like the poor, tribals, Muslims and Patels against the style and substance of his leadership. What is more, Modi has proven his invincibility, and that too on his own terms.

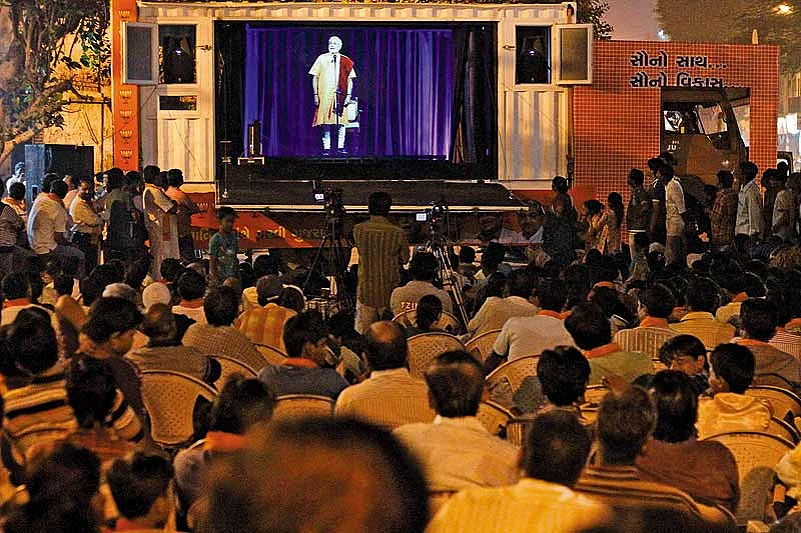

Much was made of the Gujarat chief minister’s so-called 3-D virtual campaign; but much before the 2012 battle began, Modi and his handlers had put in place a sophisticated campaign centred on another set of three Ds: deception, disrespect and dabangiri.

The element of deception has been in the making for the last three years. Its central objective was to manufacture a ‘false consensus’ in which Modi became synonymous with ‘development’, as if Gujarat was a total stranger to concepts and practices of ‘development’ before the BJP’s inner intrigues saw him oust Keshubhai Patel from the CM’s office in 2001. The ‘sadbhavna’ farce was part of this carefully crafted deception; it enabled the moderate, reasonable and secular Hindu middle classes to believe that perhaps the chief minister has turned a new leaf. So successfully has this false consensus been cemented up that New Delhi-based professional hype-meisters have become his ‘(un)paid’ acolytes, and who easily bought into ‘the inevitability of Narendra Modi as the prime ministerial candidate’ project.

The second D in the Modi spiel was the invocation of ‘disrespect’ as a defining attitude. The CM demonstrated a natural absence of any restraint in calling his rivals names, not because of personal animosity but as part of an expedient calculation, aimed at catering to our baser instincts. In particular, Modi unveiled a cheerful disposition to be roughly disrespectful towards the Nehru-Gandhi family or Prime Minister Manmohan Singh or Ahmed Patel.

The third ‘D’ can only be described as dabangiri: a massive and unorthodox use of the state police and its coercive machinery to instil a sense of fear among all detractors, particularly the minorities. After the sadbhavna farce had served its purpose, Modi turned his back on Muslims and excluded them from any representation in the BJP’s list of candidates. In the last days before the elections, the police in the urban areas (which have provided the decisive seats) was commandeered to send out a message to the minorities to behave and to just keep in mind that the central forces would eventually go back after the votes had been counted.

What has gone largely unnoticed is that Modi practised his dabangiri vis-a-vis the BJP too; not only did the central leadership have no say in selection of the candidates, but national leaders like Sushma Swaraj and L.K. Advani were corralled into giving certificates of prime ministerial eligibility to the CM, and then were scrupulously kept out of the campaign. The national leaders were welcome to come to Ahmedabad and address press conferences, but not a public meeting. The central leadership had no choice but to swallow this.

Modi cannot be grudged his victory. Particularly because, unlike 2002 and 2007, he did not have the local stormtroopers of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh in his corner; he could do without the VHP or RSS karyakarta and his much-vaunted ‘energy’. This is a bitter lesson that the Nagpur cabal will have to factor in before the thinking of rearranging the BJP leadership musical chairs.

Having tamed the BJP high command and the RSS, Modi’s handlers will want to position him as the party’s prime ministerial mascot. The success of this project will hinge on how the Modi phenomenon is understood by different political formations and forces.

It cannot be over-stressed that the Modi promise is woven around two vital elements. One: Modi is perhaps the first politician since the Swatantra Party days who is not apologetic about his open links with capitalist honchos. His decade-old regime was propped up by four corporate groups, who managed to get all the policy breaks, and who in turn have only been too happy to use their financial clout to help the chief minister tame his detractors in politics, bureaucracy, media and civil society. This corporatist bias—which in other parts of the country would have been seen as unabashed crony capitalism—is at the very core of the Modi model of development. In recent years, many ‘respected’ corporate voices have allowed themselves to be seen as endorsing this Modi model of capitalist-led development. It may have its attraction outside Gujarat as well.

Second, the second defining element of the Modi leadership is a cultivated antipathy to minorities. This remains the core of his appeal among his flock and self-imagined political persona. But this will not and cannot have any traction outside Gujarat. Sober and serious politicians across the country have watched with apprehension Modi’s ability to galvanise and convert this antipathy to minorities into an electoral asset.

After the Gujarat verdict, the BJP is stuck with Modi. In the run-up to the 2014, the name of the game will be the creation of umbrella alliances: ability of the two rival camps—the UPA and the nda—to hold on to their current partners as well as to attract new allies. The strategic question facing the BJP and the rest of the NDA remains: is Modi the man to help expand the alliance and convert it into a winning proposition?

On the other hand, the Himachal Pradesh victory and a respectable show in Gujarat don’t spell unmitigated disaster for the Congress and its UPA allies. The combined outcome in the two states should enable the Congress managers to renew their conversations with all those parties and groups who believe in equity, inclusiveness and social harmony. The Congress showed considerable finesse in its Gujarat campaign and lives to fight another day; in Himachal Pradesh, neither charges of corruption against Virbhadra Singh nor price rise/lpg cap seemed to hurt it. And if the Congress can weave the lessons from Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh into its 2014 narrative, it may do itself a good turn. Whereas Narendra Modi’s hat-trick can only aggravate the BJP’s internal leadership turmoil, the Congress, for better or worse, is happy to be stuck with Rahul Gandhi at the moment.

In fact, Rahul Gandhi and his many teams can be expected to take heart from Modi’s success: if a man who ten years ago was just a district-level leader can be packaged and sold as the BJP’s best national bet, surely there was at least some hope for the ‘young prince’. The Congress strategists may not be all that averse to having an unrepentant Modi as the nda’s prime ministerial mascot.

On the eve of the 2009 Lok Sabha election, the BJP had sought to sell Advani as a man without rough edges and a consensus-builder. In its editorial, dated March 16, 2009, the party mouthpiece Kamal Sandesh had formulated: “India today needs a leader who is acceptable to all, who appeals to all and who touches the heart of everyone. And that person is and can only by Shri Lal Krishna Advani”.

Modi fails the Advani test. The polity is no less fractured today than it was in 2009, and there will be no dearth of prima donnas in 2014 who would need to be cajoled and appeased—something Modi abjures. He has tasted success on his terms, and it would be unrealistic to expect him to abandon his systematically honed personality cult. The rest of the polity, including the BJP, will have to take a call on the Modi model of leadership and its inherent authoritarian ambience and corporatist tilt. And, let there be no mistake, there is no Modi a la carte. It is a fixed Gujarati thali. Take it or leave it.

(Former media advisor to the prime minister, Harish Khare is the recipient of the Jawaharlal Nehru fellowship for 2013)