Nearly four years after the abrogation of Article 370, change is afoot in Srinagar. It is evident on the streets of the capital, in its people and on new signages in the city. Near the Zero Bridge, an Akash Institute hoarding invites students to excel in competitive exams at its Rajbagh branch. The institute-chain was acquired by BYJU’s, an edu-tech behemoth with 500 centres in 200 Indian cities. Its offline branch by the Zero Bridge is now part of a pan-India network.

Paramilitary forces stationed in three fortified bunkers continue to patrol near Church Lane by the Bridge. Though the once unsettling routine frisking of passers-by has somewhat lessened, the men in olive green are still there, behind wire-clad posts, suggesting that while some things appear to have changed in Kashmir, they are still the same.

Rajbagh, a posh address in Srinagar, appears to be flourishing with new buildings, new houses, new hotels and tuition centres. The Zero Bridge, which was washed away in the 2016 floods, is now a tourist destination, where tourists spend hours watching the Jhelum jostle by.

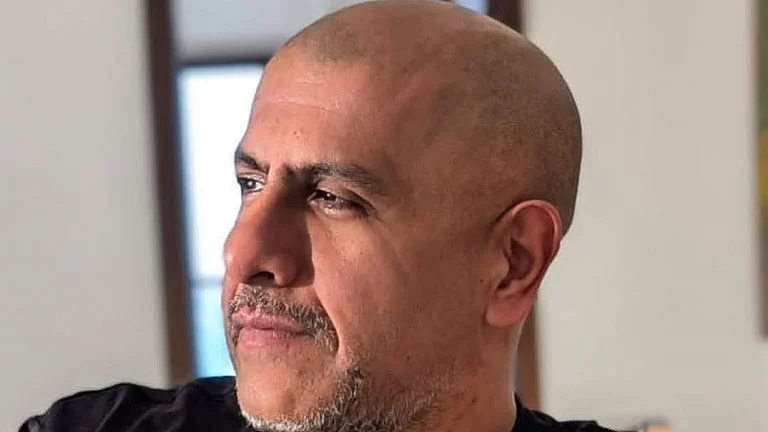

There is another pair of eyes on the Bridge: that of a native, Irfan Ahmad, a businessman in his early 50s. He, too, watches the river flow by peacefully. But in his heart there’s turmoil. Ahmad has been deeply impacted by the import of the recent Supreme Court decision upholding the central government’s move to abrogate Article 370 of the Indian Constitution.

He is “crestfallen”. On the verdict day, Ahmad was at a condolence meeting. He believed the country’s top court would rule against abrogation. “I felt (like) someone stabbed my heart. Incidentally, I was at a condolence meeting, a perfect place to mourn,” he says. As he tries to elaborate, his friend intervenes, urging him to “avoid” political talk. Ahmad, too, perhaps realises the gravity of his comments and stops the conversation abruptly.

Ahmad’s caution and unease reflect a widespread fear of discussing the current political situation in the Valley.

On December 11, a five-judge constitution bench headed by Chief Justice D Y Chandrachud upheld the abrogation of Article 370 as “constitutionally valid” in its verdict on a clutch of petitions challenging the abrogation filed by the National Conference (NC), Peoples Conference, CPI(M), the local High Court Bar Association and former bureaucrat-turned politician Shah Faesal.

The petitions were filed days after August 5, 2019, when the BJP government revoked Article 370 and Article 35A of the Indian Constitution, bifurcating Jammu & Kashmir and downgrading the now-former state into two Union Territories, Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh.

Following the verdict, the only comfort for regional political parties lies in the Apex Court’s directive to the Election Commission (EC) to conduct elections by September 2024, also urging the government to promptly restore statehood.

The long-drawn legal battle was not without surprises.

Shah Faesal had already withdrawn his petition months before the final hearing, claiming Article 370, for many Kashmiris like him, was a thing of the past. “Jhelum and Ganga have merged in the great Indian Ocean for good,” he had proclaimed.

Unlike Faesal’s ‘change of heart’, young singer Jibraan Nasir, who Outlook met by the Bridge, appears to be oblivious to the development, which has the potential to tectonically alter the unique identity of the region.

Unlike the charged atmosphere of the pre-Article 370 era, when artists, poets, rappers and singers were more vocal about the region’s politics, Nasir claims he is simply disinterested.

“I am an artist and I will not talk about politics,” he says. “Even on the day of the verdict, I was with other friends and didn’t take notice of what happened.”

According to a human rights lawyer, people now fear that the government might know what they are thinking just by looking at their faces. “It seems bizarre, but it is so true,” he humorously chips in.

Where else could people talk? “Dal Lake!” quips a photojournalist, who was within earshot.

At Ghat number 12, 72-year-old Shikrawalla Mohammad Abdullah Sagdu bemoans the tourism slump this season as the temperature in Srinagar during the night drops to minus six, affecting his boat business.

He initially opens up about Article 370. “Article 370 was ingrained in our lives, a part of our identity. Its removal was unwarranted,” he says. But Sagdu hesitates to discuss the impact of its abrogation on Kashmir and its people. “We have left everything to God. Let us see what God has in store for us,” he says.

Sagdu navigates past flower-laden boats and tourists, halting at Tariq Ahmad Patloo’s ambulance boat. Tariq, known for ferrying patients across the water, expresses dissatisfaction over Article 370’s removal. But his cousin, Mohammad Yasin, a 45-year-old businessman, who was initially saddened by the move, now supports it. He believes the Valley requires peace and stability. Yasin, who was in Ukraine during the abrogation, now says that Article 370 should have been abrogated earlier.

“There are no stone-throwing incidents, no strikes. There’s a semblance of peace in Kashmir. Tourists are arriving in large numbers. What more could you ask for?” he says.

Kashmir has “faced a severe crackdown on media freedom, including arbitrary arrests and communications blackouts,” according to the International Press Institute’s latest report. The state of journalism worsened post-August 2019, after the Indian government revoked Article 370, removing Kashmir’s autonomous status, the report says.

After the Supreme Court’s confirmation of the abrogation, an upbeat Lt Governor Manoj Sinha, known for criticising regional parties, hailed Prime Minister Narendra Modi for laying the foundation for a “New J&K” on August 5, 2019.

Optimistic about the future, he said, the SC verdict brings hope and strengthens the nation’s unity and integrity. “After the abrogation…strike calendars are not issued by our neighbouring country and stone-pelting has become history,” Sinha said, adding that by November this year, tourist footfalls to J&K had surpassed two crore.

However, J&K was initially hit by curfew-like restrictions after the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019 and later by COVID-19 curbs in 2020, and regional parties dispute Sinha’s figures. They allege the government inflates numbers by including pilgrims visiting the Mata Vaishno Devi Shrine in Jammu to project the figures in crores.

On August 2, 2019, just before the abrogation, government orders in view of possible terror strikes had created panic in Jammu and Kashmir. Tourists and pilgrims were instructed to leave immediately, severely impacting the flourishing tourism sector. Following that advisory, the UK, Australia, the US and Canada issued their own travel advisories for Kashmir. Despite easing restrictions in 2020, none of the countries lifted or modified their previous adverse advisories. In 2020, only 41,267 tourists, including 3,897 foreigners, visited Kashmir, marking the lowest number since 1990.

Prior to Article 370’s removal, massive force deployment, augmenting paramilitary presence, hinted at a war-like scenario before the abrogation shockwave eventually hit the Valley on August 5, 2019.

Since December 2021, the Valley’s tourist numbers have significantly increased, months after the government released a 76-page booklet titled ‘Jammu and Kashmir Marching To A New Era’. The booklet listed the central government’s achievements in J&K, crediting the central government’s ‘‘One Nation, One Constitution On Flag’’ resolve and application of 890 central laws to the two Union Territories, including rights for weaker sections, children, senior citizens, laws for governance, new land, and domicile laws facilitating citizenship.

Nearly five years after abrogation, security forces remain prominent in Kashmir and the practice of halting traffic for army or paramilitary convoys persists.

Irrespective, Yasin hopes for the better and for a bigger tourism boom. “I believe whatever happened was for the better...It’s time for us to move on and welcome foreign and Indian tourists to Kashmir,” he says.

At Srinagar’s iconic city square Lal Chowk, a separatist leader taking a stroll on a crisp, cold day, is critical of Pakistan’s statements on Kashmir. Pakistan’s implicit endorsement of Article 370’s abrogation became evident in the 2021 ceasefire reaffirmation, signifying consent, he claims. He advocates negotiating with New Delhi to preserve land, employment and demographics, provided the government engages in such discussions. “I don’t see any other alternative,” he says.

There are many like him, who bemoan lack of options and harbour no hope that the Apex Court will ever overturn the government’s significant political and geostrategic decision.

The paucity of options has made Mohammad Yousuf, a houseboat owner, anxious. “Article 370 provided safety to Kashmiris, their identity and the region’s demography,” he says, worried about their future.

Amidst India-Pakistan tensions, on February 25, 2021, the Directors-General of Military Operations from both countries had issued a joint statement, urging adherence to existing agreements, understanding and a ceasefire along the Line of Control (LoC), effective from midnight on February 24-25 that year.

Since the 2003 ceasefire, both India and Pakistan, despite initial scepticism, have maintained the status quo, even after the revocation of Article 370 in 2019. Contrary to expectations, no ceasefire violations occurred in 2022, in stark contrast to the 740 violations recorded from Pakistan up to February 24, 2021. The LoC border areas in J&K, once tense, are now emerging as new tourist destinations.

Two days after the Supreme Court verdict, the National Conference (NC) office is deserted. Party spokesman Imran Nabi Dar wasn’t at home when the apex court pronounced its verdict. “I had to be at a different place other than my house, as I suspected the police had the same plan that it executed in 2019 before the abrogation: to arrest all leaders,” he claims. He was called to the local police station on December 11 ahead of the SC order. “I told the caller that I’m not a criminal and will not come to the police station,” he adds.

Two days before the verdict, district magistrates across Kashmir issued orders directing “online unregistered news portal or social media platform” not to publish any current affairs without any verification and accountability. The Cyber Police Kashmir too issued an advisory asking all social media users to use “social media responsibly” and refrain from sharing “any rumour”. The pattern was similar to orders issued days before August 5, 2019.

Dar anticipated a favourable Supreme Court verdict, on account of arguments posed by lawyers Kapil Sibal and Gopal Subramaniam, representing the NC petition. The NC, he says, will continue to talk about the restoration of the region’s special status. “Nothing stops us from talking about the restoration of the special status. The party will fight for it,” he says.

In August, the NC, optimistic about its robust legal case, fervently campaigned for elections in J&K. The verdict, however, has dashed their enthusiasm, particularly that of Vice-President Omar Abdullah. Party President Farooq Abdullah was so dejected by the verdict that he even told reporters in Delhi, “Let J&K go to hell.”

With no specific direction from the Apex Court on statehood restoration, Dar fears the government may prolong J&K’s reinstatement to statehood.”We had gone to Court to challenge the abrogation of Article 370 and instead, they gave the Election Commission of India directions to hold polls in September 2024. Why not hold polls now with the Lok Sabha elections? What if the ECI refuses to adhere to directions in September 2024 too, citing some excuse?” Dar asks, adding that the BJP’s claim about development and ending militancy in J&K has been always contested. “But no one listens,” he counters.

In the course of the hearings in the Apex Court, the Centre submitted before the five-judge Constitution bench that “since 2019, the entire region has witnessed an unprecedented era of peace, progress and prosperity”. The Centre had also claimed the region’s return to normalcy after three decades, with the end of daily strikes, stone-pelting and bandhs.

“The development projects executed by the government at present were started by previous governments,” Dar insists. “They have developed Lal Chowk and the Jhelum bund as Smart City projects. That is all they showcase. Let them show tourism figures for 2011, 2012 and onwards. The present figures are slightly higher. That is all,” he adds.

Despite deadly attacks since 2019 in the Pirpanjal mountain range, the government avoids discussing the ongoing militancy in Rajouri and Poonch, Dar says, adding that militancy is in fact on the rise there after a lull of 15 years. On November 17, in the Rajouri jungles, terrorists ambushed and killed five army personnel, including two officers. This year witnessed 14 army casualties in five major terror incidents, with back-to-back ambushes on April 20 and May 5 claiming 10 lives. Since October 11, 2021, the region has faced increased militant violence, with two encounters resulting in nine army fatalities. On January 1, 2023, terrorists targeted minority community members in Rajouri, killing seven civilians, including two minors, through firing and an IED blast at Dhangri village.

But local police claimed in October that J&K’s militant count has hit an all-time low, about 50, resembling 2013 levels. Top police officials told the media in J&K that they “achieved a significant milestone in the fight against terrorism this year,” with the Union Territory “witnessing the lowest number of terror incidents and civilian deaths in over three decades.”

Earlier, the best year in terms of security was 2013, which witnessed the lowest level of militancy, police claimed, inadvertently acknowledging that militancy was also low a decade earlier too. Terror-related cases have plummeted from 113 in 2013 to a mere 42 in 2023 and in 2018, while 210 persons joined militancy in 2023, the figure was down to a mere 10, with six of them killed, police said.

PDP’s Mehbooba Mufti—a vocal government critic—likened J&K’s current state to occupation following the Supreme Court verdict. “What is the difference between an occupation and a government?” she asks, quoting Arab poet Ansar Yawar. “Expecting a solution from those who created the web is like a bug asking the spider for its freedom, not realising the purpose of the web.” Many in the PDP feel that approaching the Supreme Court was a mistake, as Article 370 was the result of a pact between J&K and the Centre, ratified by the Constituent Assembly even before the Supreme Court’s existence. “How can a pact between Jammu and Kashmir and the Government of India, duly recognised by the great leaders of both sides, be set aside by the Court?” they ask.

Former MLA Mohammad Yousuf Tarigami, spokesperson of the Peoples’ Alliance for the Gupkar Declaration, an amalgam of regional parties, on the contrary, claims that that the Supreme Court is an important institution vis a vis the issue of restoration of Article 370. “It upheld the abrogation of Article 370, but it also stated that the procedure adopted to abrogate is ultra-vires. The Court didn’t address whether a state can be turned into a Union Territory legally. I am in touch with my legal team to explore further legal options,” he says.

Tarigami says that after the abrogation of Article 370, thousands have been booked under the Public Safety Act and the UAPA and other laws. “The jails of J&K are overcrowded. The government and the BJP often say there is no protest in Kashmir and everyone is silent. They don’t tell us whether they allow anyone to even squeak. If you post anything on social media, you are booked. Imagine if someone comes out to protest. Have you ever seen protests in Tihar jail?” he asks.

In his room, lines from Faiz Ahmad Faiz’s poem ‘Bol ke lab azad hain tere’ and Habib Jalib’s verse ‘Zulm rahe aur aman bhi ho, kya mumkin hai tum hi kaho’ are on display. Tarigami points to Faiz’s poem, declaring it is time to speak up. “The Supreme Court verdict hasn’t sealed the fate of Article 370. The five-bench judgement has big loopholes,” he claims, optimistic that a larger bench would be able to see through them. But voices in the Valley—on Zero Bridge and at Lal Chowk—appear to be reluctant to share his optimism.

Naseer Ganai in Srinagar

(Edited by Mayabhushan Nagvenkar)

(This appeared in the print as 'A 370º Turn' )