Bordering the volatile Sukma district in the Bastar region of Chhattisgarh, the little hamlet of Neelavaya in Dantewada district is home to about 700 people. Apart from a handful, who stayed outside the village, not a single person showed up to vote on November 7 when Bastar went to polls.

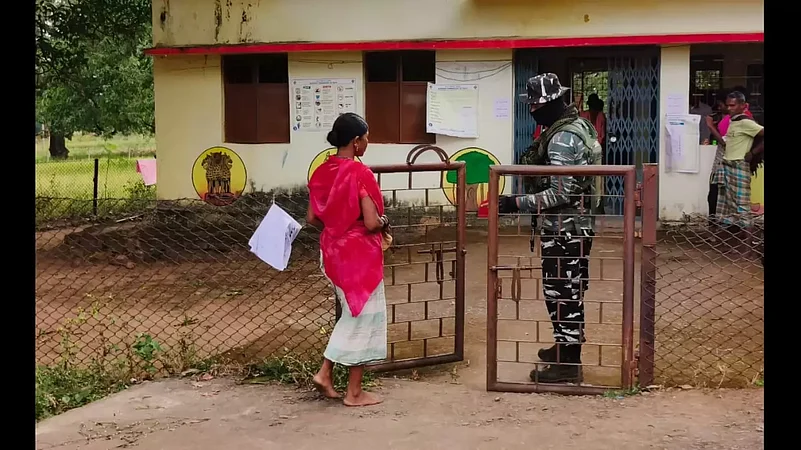

The first phase of the Chhattisgarh Assembly Elections saw a high voter turnout at around 71 per cent, even as violence continued across the Bastar region through the day. The fear of violence among voters could be felt in the region's eastern side of the Indravati river which are Naxalite strongholds like Neelavaya, where voters refused to leave their homes despite heavy security presence and three-layer cordons at poll booths. “Whether someone wants to risk their lives to vote or not is and should be their personal decision,” Ramesh Korrum, a resident of Neelavaya says tersely when pressed.

Neelavaya is the same village where two security personnel and a journalist were killed in a Naxal ambush ahead of the last elections in the state in 2018. By 1 p.m., only one person from Neelavaya had voted at the polling booth in Aber panchayat, located in a sensitive zone. Residents of another village under the panchayat, Berra, which also lies across the river, did not show up as they claimed to not have been informed about the location of the polling booth.

Meanwhile, in Bijapur district, villagers of Chihka village in Behramgarh block which is adjacent to the heavily militarised Abujhmarh hills, turned up to vote despite a call for a poll boycott by the Naxals. The villagers nevertheless refused to get their fingers marked with permanent ink for fear of retribution from Naxals. Nevertheless, villagers from interior regions were showing up to the Chihka polling booth, some even walking for 7-10 kilometres to exercise their right to vote. By afternoon, several polling booths in Bijapur such as Marubaka - II, Pusbaka, and Thimmapur, had zero to a maximum of five votes. Villages were reportedly emptied by Naxals ahead of polls.

Elections in Bastar with its 12 assembly constituencies (including Bastar) have always been marred with violence between security personnel and Naxals who do not accept the elected Indian government. Despite heavy assurances by the election commission and Chief Minister Bhupesh Baghel, this year was no different.

Sukma with 195 polling booths where the Naxals had called for a poll boycott saw persistent violence between security forces and the former. A gunfight broke out in Durma village of Mehta district in the initial hours of voting. Naxals also fired upon DRG personnel, two kilometres away from the Banda polling booth in Konta. The two sides were engaged in fighting for nearly half an hour in Kanker where Naxals fought BSF and Bastar Tigers personnel. CRPF and Naxals also faced off in the area between Tadmetla and Dukes. In Minpa, Naxals attacked soldiers of the elite anti-Naxal force CoBRA who were posted inside forests to assist voters in reaching polling booths from inward villages. Violence also took place in Bijapur, a region south of Padeda. The personnel were reportedly part of the CRPF 85 battalion and were out on area dominion duty when the ambush took place. Videos shot via drone in the aftermath of the skirmish show what appears to be a team of Naxals carrying two injured or dead persons as they walk into the thick of the forest. A villager was also reportedly shot in the leg, though police have so far refused to divulge the details of the case. The morning also saw an IED blast in Sukma which left a security personnel injured and IEDs were also discovered intact in areas like Dantewada.

Nevertheless, voters in some regions seemed enthusiastic about voting and came out in large numbers. With 126 new stations set up in remote villages, many areas which were previously sensitive could be brought under the electoral fold. The lowest voter turnout was seen in Bijapur where it was 40.98 per cent while Bastar and Narayanpur assembly constituencies saw over 60 per cent polling. Incidentally, villagers of Kushalgarh in Narayanpur where a BJP worker - Dubey - was hacked to death by Naxals three days ago while campaigning, saw a high voter turnout as villagers braved it out to vote in defiance of the violence, with 375 out of 613 voters. Bhanupratapupur achieved the highest turnout at 79.10 per cent.

First-time voters in Dantewada like Sukhmati from Patelpara village who came to vote at the Palnar village polling booth, about 15 kilometres away from their village, stated that they wanted to vote because they wanted good jobs with salaries. “We are educated but we don’t have any work,” she and her friends stated while waiting in queue to vote at the crowded station. 22-year-old Jiteshwari Sinha, a horticulture student at Kishori Pandit Lal Shukla College said that voting was the only way to elect an educated and responsible government. “Dantewada is very backwards compared to the rest of the country. It’s only when educated people like us come to vote for educated leaders that things can really change on the ground in terms of infrastructure or security” she said.

But away from the bustle of voting, several adivasis living in Naxal zones across the Indravati but are not part of the armed resistance movement or left-wing extremism have also boycotted elections. People like Sunita Tam of Blear village or Vinesh Kumar Podiyam of Rekhawa who have decided not to vote for any party this time as they feel no government cares about the needs of Adivasis. They claim that rampant development projects in the area are intended to only help the government or party in power and “their industrialist friends”. “They are taking away our indigenous natural resources and giving nothing back to the indigenous population - the true owners of the jal, jangal, and jammer of Bastar,” he states.

Along with him, thousands of Adivasis, especially in the Bijapur district, have been protesting for nearly two years against the construction of multiple “puliyas” across the river Indravati which they claim are unnecessary and that the government is only constructing them to ease mining work in the region which they oppose for its adverse effects on tribal resources and the ecosystem. The tribals also claim that despite having education and skill, they are denied public jobs while outsiders are appointed. “When we complain, the police and administration call us Maoists and lock us up or worse, kill us,” he added. Such discontent among voters could be one of the reasons that explain the low turnout in Bijapur.

Is it only violence by Naxals that makes electoral democracy difficult in Bastar? What happens when the democratically elected government fails to meet the needs of its voters, the same people who helped them win? According to Adivasi leaders and Bijapur candidate Ashok Telandi from the newly formed Hamar Raj Party, neither the Congress nor the BJP have ever cared for the tribals. “Despite having tribal faces, these parties don’t work for the empowerment of the communities. That is why any development they do is without consultation with locals,” he states. Hamar Raj Party was formed by former Congress leader Arvind Netam in the run-up to the elections in a bid to wrest power from the two big players of Chhattisgarh and give it to an independent tribal body. In an interview with Outlook, Netam states that the problem of Naxalism is a complex one that goes beyond its violent outer shell. “At the core of the issue is the failure of the government - both at the centre and the state - to provide adequate education, livelihood, health and dignity of life to tribals of Bastar. That is where we need to look to truly solve the Naxal problem,” he states.

A historic example of this neglect can be seen in the Chandameta village of Bastar district which saw elections for the first time in 75 years since India’s independence. It was among the 126 villages in sensitive zones which got polling booths for the first time this year. In an antithesis to the voters of Neelavaya, the over 300 voters who showed up at the polling booth in the newly opened school were aware of the historicity of the moment and seemed glad to finally be part of the biggest democracy in the world. The Pahurnar village polling booth in the Abujhmarh area also saw over 700 voters, an increase from previous years, despite Naxal's presence. "It is our right to vote," first-time voter Ratan Kodiam said. In another happy instance, a queer-friendly "rainbow polling booth" was set up in Pankhajur where a large number of transgender voters reside. The sight of the voters, dressed to the nines in starched sarees and arriving through a decorated rainbow-coloured tunnel to cast their votes was a paradoxical sight in the otherwise khaki-coloured Bastar. One that gives a glimpse into a Bastar that remains undiscovered.

The elections this year gave a glimmer of hope for democracy and indigenous assertion of Adivasis in the region. But for how long can democracy be imposed at the point of a gun?