Summary of this article

Social media platforms deactivated or restricted about 4.7 million accounts linked to children since Australia enforced its ban on under-16s in December.

The ban has sparked global interest, with countries such as Denmark considering similar restrictions, even as regulators monitor attempts to bypass the rules.

Social media companies have removed access to around 4.7 million accounts identified as belonging to children in Australia since the country enforced a ban on under-16s using such platforms, officials said.

“We stared down everybody who said it couldn’t be done, some of the most powerful and rich companies in the world and their supporters,” Communications Minister Anika Wells told reporters on Friday. “Now Australian parents can be confident that their kids can have their childhoods back.”

The figures, submitted to the Australian government by 10 social media platforms, are the first indication of the scale of the landmark ban, which was enacted in December amid concerns over the impact of harmful online environments on young people.

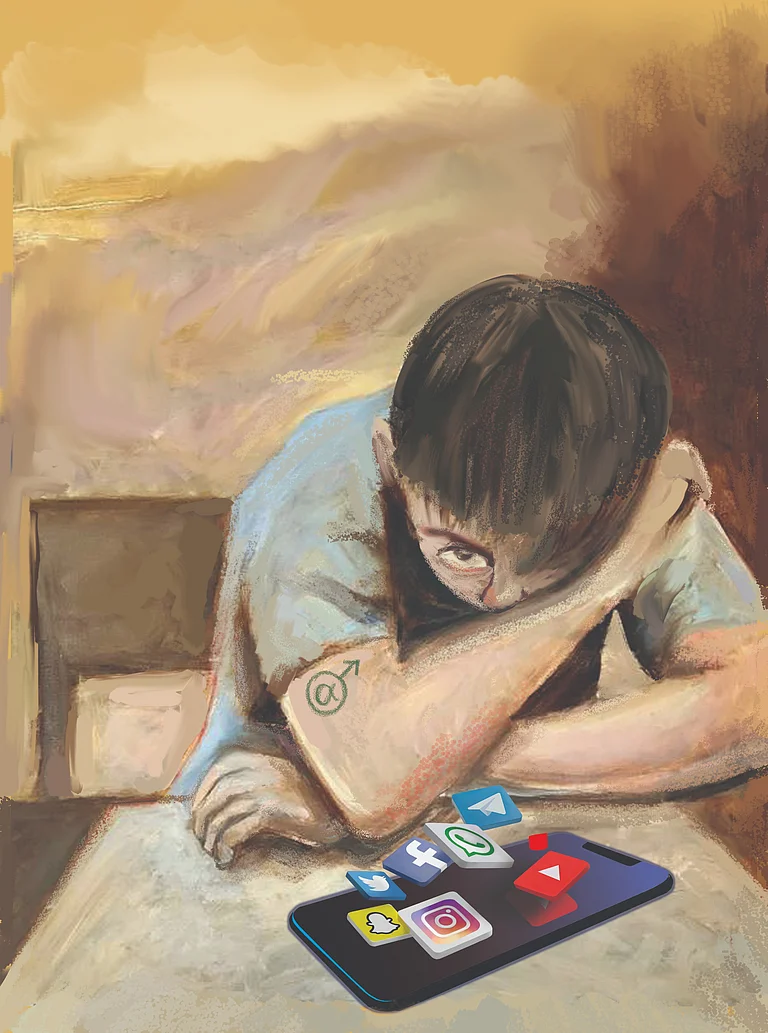

The legislation sparked intense debate in Australia around technology use, privacy, child safety and mental health, and has encouraged other countries to explore similar restrictions.

Officials said the number was encouraging. Under Australian law, platforms including Facebook, Instagram, Kick, Reddit, Snapchat, Threads, TikTok, X, YouTube and Twitch face fines of up to 49.5 million Australian dollars ($33.2 million) if they fail to take reasonable steps to remove accounts belonging to children under 16. Messaging services such as WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger are exempt.

To verify users’ ages, platforms can request copies of identity documents, rely on third parties using facial age-estimation technology, or infer age from existing data such as how long an account has been active.

Around 2.5 million Australians are aged between eight and 15, according to eSafety Commissioner Julie Inman Grant, and previous estimates indicated that 84 per cent of children aged eight to 12 had social media accounts. While it remains unclear how many accounts existed across the 10 platforms, Inman Grant said the 4.7 million accounts that were “deactivated or restricted” was a positive sign. “We’re preventing predatory social media companies from accessing our children,” she said.

The 10 largest companies covered by the ban complied with the requirements and reported their removal figures to the regulator on time, Inman Grant said. She added that companies were now expected to shift focus from enforcement to preventing children from creating new accounts or bypassing the restrictions.

While Australian officials did not provide a platform-wise breakdown, Meta, which owns Facebook, Instagram and Threads, said earlier this week that it had removed nearly 550,000 accounts believed to belong to users under 16 by the day after the ban took effect. In a blog post disclosing the figures, Meta criticised the ban and warned that smaller platforms not covered by the law might not prioritise safety. The company also noted that browsing platforms could still present algorithm-driven content to children, an issue that contributed to the law’s passage.

The ban has been widely supported by parents and child safety advocates. However, online privacy groups and some organisations representing teenagers opposed it, arguing that vulnerable or geographically isolated young people often find support in online spaces.

Some critics have claimed that children have managed to bypass age-verification tools or received help from parents or older siblings to evade the ban. As Australia debated the measures in 2024, several other countries began considering similar steps. Denmark’s government, for instance, said in November that it planned to introduce a social media ban for children under 15.

“The fact that in spite of some skepticism out there, it’s working and being replicated now around the world, is something that is a source of Australian pride,” Prime Minister Anthony Albanese said on Friday.

Opposition lawmakers have suggested that young people may be easily circumventing the ban or shifting to less-regulated apps. Inman Grant said data reviewed by her office showed a spike in downloads of alternative apps when the ban was introduced, but not a corresponding rise in usage.

“There is no real long-term trends yet that we can say but we’re engaging,” she said, adding that her office plans to introduce “world-leading AI companion and chatbot restrictions in March,” without providing further details.