Summary of this article

The author presents that language is not merely an abstract concept but a tangible physical entity.

The Pantagruelian antilanguage has its own physiology and anatomy

Pantagruel refuses to treat words as items for sale (like lawyers) or as objects to be "pickled" and preserved. Instead, he views language as living, ever-present force.

That language has a body, that the word has always already been made flesh, that it is first of all material and corporeal, is clearly shown by the extraordinary episode of the frozen words in the Fourth Book: ‘At [the onset of last winter], the Words and cries of men and the women [ . . . ] froze in the air. And now that the rigour of winter has passed and fine, calm, temperate weather returned, they melt, and can be heard’ (Rabelais, p. 829), at which point Pantagruel can grab some still-unthawed ones and throw fistfuls of them at his friends. The words—coloured azure, sable, golden—

after they had been warmed up a little in our hands [ . . . ] melted like snow, and we actually heard them but did not understand them, for they were in some barbarous tongue, save for a rather tubby one which, after Frère Jean had warmed it in his hands, made a sound such as chestnuts make when they are tossed un-nicked on to the fire and go pop. (p. 829)

Beyond the imaginative invention, the frozen words are in some way the paradigm of the new Pantagruelian antilanguage—horrific and bloody and yet fully aware of its own dignity. When Panurge asks him for another fistful of words, the giant objects that ‘Giving Words is what lovers do’; nor can they be sold, as his friend then requests, because ‘selling Words is what lawyers do’; ‘I would rather,’ he immediately adds, ‘sell you silence more dearly’ (pp. 829–30).

In any case, what is at issue here is the unprecedented body of language, a body that lets itself be seen, bleeds and rumbles:

And I saw many sharp Words, and bloodthirsty Words too (which the pilot said come home to roost with the man that uttered them and cut his throat); there were dreadful Words, and others unpleasant to behold. When they had all melted together we heard: Hing, hing, hing, hing: hisse; hickory, dickory, dock; brededing, brededac, frr, frrr, frrr, bou, bou bou,bou, bou, bou, bou, bou. Ong, ong, ong, ong, ououououong; Gog, magog and who-knows-what other barbarous words; and the pilot said that they were vocables from battles joined and from horses neighing at the moment of the charge; and then we heard other ones, fat ones which made sounds when they melted, some of drum or fife; others of bugle and trumpet. Believe you me, they provided us with some excellent sport.

I had hoped to preserve a few gullet-words in oil, wrapping them up in very clean straw (as we do with snow and ice); but Pantagruel would not allow it, saying that it was madness to pickle something which is never lacking and always to hand. (p. 830)

Language is not—contrary to a stale doctrine that the West tirelessly repeats—the sign of a mental concept: it is first of all a body that can be seen, heard and touched—a body that, like those of the giants, has its own physiology and its own anatomy, fingernails and heels, buttocks and belly, nerves and armpits. In any case, one does not understand the doctrine of Rabelais and Folengo, of Pantagruel and Baldo, of Cingar and Panurge, unless one resolutely places oneself at the point where the two bodies intersect.

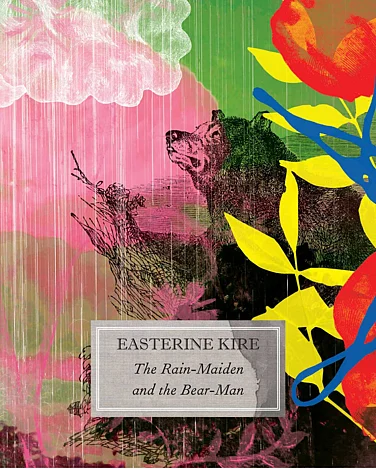

Excerpted with permission from Seagull Books.