Summary of this article

The studio is the image of potentiality—of the writer’s potentiality to write, of the painter’s or sculptor’s potentiality to paint or sculpt.

Agamben writes, 'One cannot have a potentiality; one can only inhabit it'.

The author believes one knows something only if one loves it.

A form of life that keeps itself in relation to a poetic practice, however that might be, is always in the studio, always in its studio.

(Its—but in what way do that place and practice belong to it? Isn’t the opposite true—that this form of life is at the mercy of its studio?)

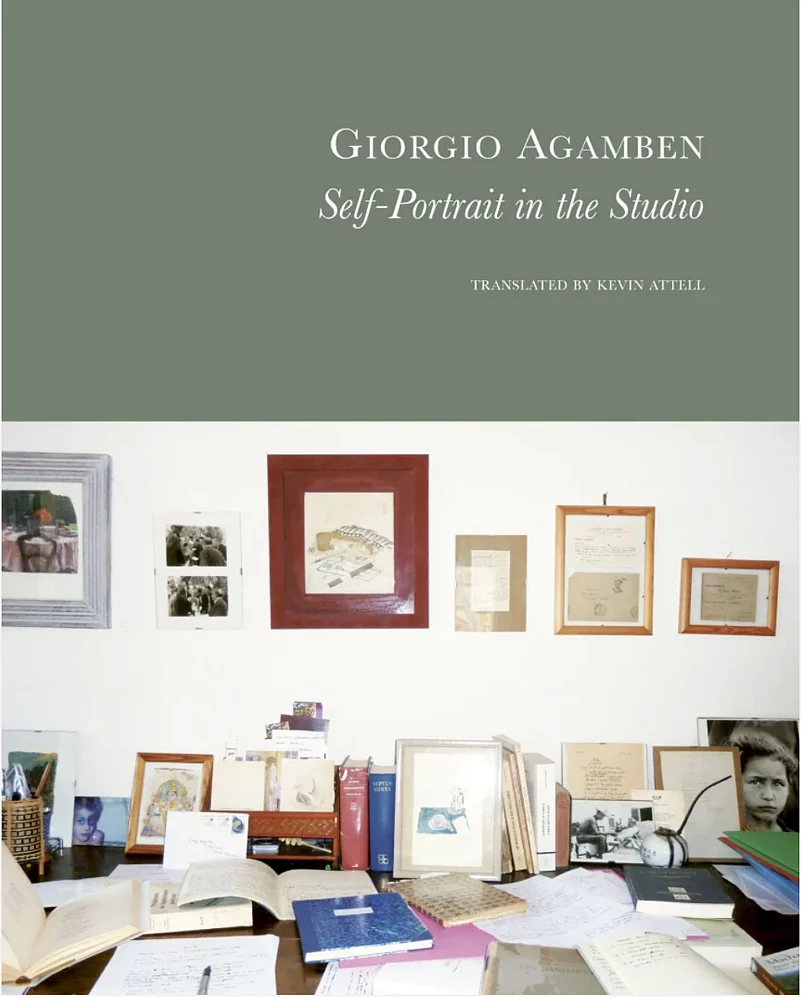

In the mess of papers and books, open or piled upon one another, in the disordered scene of brushes and paints, canvases leaning against the wall, the studio preserves the rough drafts of creation; it records the traces of the arduous process leading from potentiality to act, from the hand that writes to the written page, from the palette to the painting. The studio is the image of potentiality—of the writer’s potentiality to write, of the painter’s or sculptor’s potentiality to paint or sculpt. Attempting to describe one’s own studio thus means attempting to describe the modes and forms of one’s own potentiality—a task that is, at least on first glance, impossible.

How does one have a potentiality? One cannot have a potentiality; one can only inhabit it.

Habito is a frequentative of habeo: to inhabit is a special mode of having, a having so intense that it is no longer possession at all. By dint of having something, we inhabit it, we belong to it.

The objects of my studio have remained the same, and years later in the photographs of them in different places and cities, they seem unchanged. The studio is the form of its inhabiting—how could it change?

In the wicker letter tray against the wall at the centre of the desk in both my studio in Rome and the one in Venice, on the left there is an invitation to the dinner celebrating Jean Beaufret’s seventieth birthday, on the front of which is written this line from Simone Weil: ‘Un homme qui a quelque chose de nouveau à dire ne peut être d’abord écouté que de ceux qui l’aiment.’ The invitation carries the date 22 May 1977. Since then, it has always remained on my desk.

One knows something only if one loves it—or, as Elsa would say, ‘only one who loves knows’. The Indo-European root that means ‘to know’ is a homonym for the one that means ‘to be born’. To know [conoscere] means to be born [nascere] together, to be generated or regenerated by the thing known. This, and nothing but this, is the meaning of loving. And yet, it is precisely this type of love that is so difficult to find among those who believe they know. In fact, the opposite often occurs—that those who dedicate themselves to the study of a writer or an object end up developing a feeling of superiority towards them, even a sort of contempt. This is why it is best to expunge from the verb ‘to know’ all merely cognitive claims (cognitio in Latin is originally a legal term meaning the procedures for a judge’s inquiry). For my own part, I do not think we can pick up a book we love without feeling our heart racing, or truly know a creature or thing without being reborn in them and with them.

Excerpted with permission from the Seagull Books.