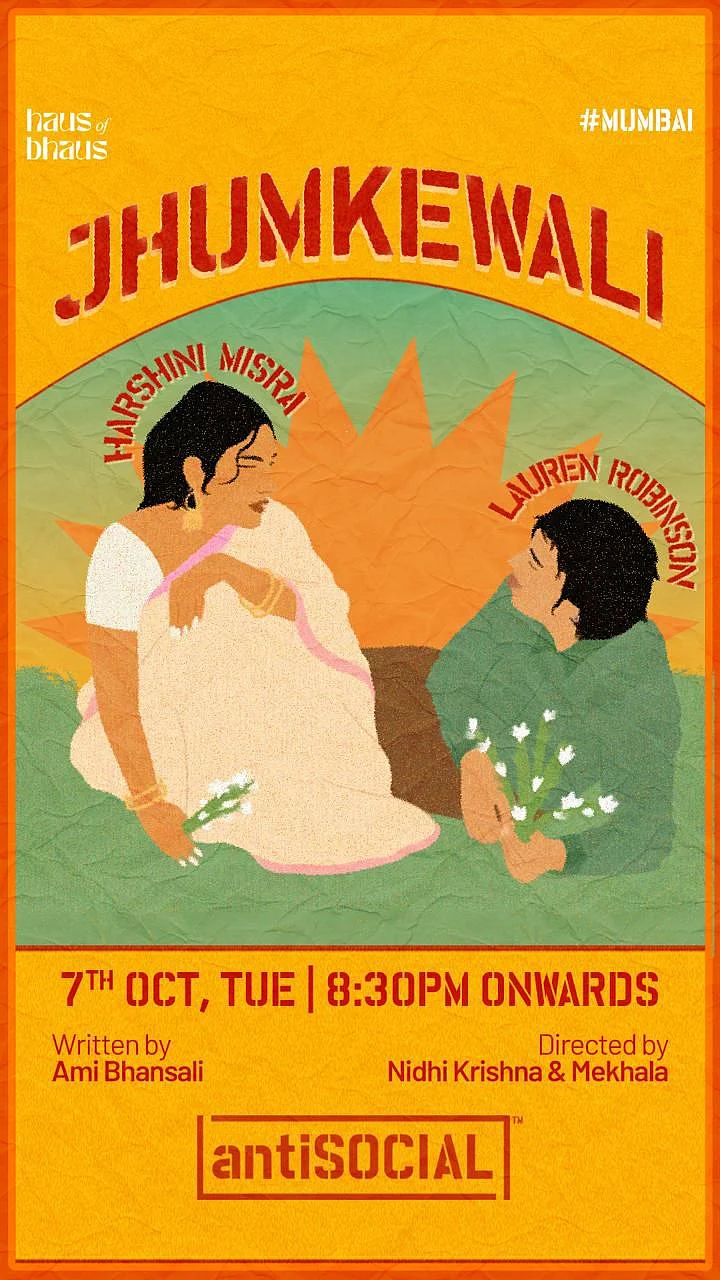

Jhumkewali is hausofbhaus’ debut-play written by Ami Bhansali and co-directed by Nidhi Krishna & Mekhala Singhal.

Jhumkewali features Harshini Misra and Lauren Robinson in lead roles.

It features themes like queer joy, self-exploration and political unrest in 70s Bombay.

“When I fall in love, I’ll believe in it like the ultimate truth. All else will be… irrelevant.”

Mumbai’s local trains have long been accidental matchmakers cradling chaos, tenderness and colourful romances. Among them are countless queer stories that have remained an ever-existent pulse. There is an absurd beauty in how love finds one in the rush-hour blur, as if the entire crowd exists merely as an elaborate distraction for a single gaze that is destined to meet yours. Jhumkewali, hausofbhaus’ debut production, written by Ami Bhansali and co-directed by Nidhi Krishna and Mekhala Singhal, doesn’t attempt to label this feeling—it simply allows it to exist and blossom. The play wonders if two people can exist in love without ever naming it, yet still build an entire language out of stolen glances and shared silences. It glides between the private and the public, where the act of loving becomes both rebellion and relief against a city that never slows down.

Set in the frenzied 70s, the play opens with a misplaced earring and a fated connection. Rekha (Harshini Misra), a polka-dot clad, dreamy-eyed English student, misplaces her jhumki on a crowded train, and in comes Bindu (Lauren Robinson), the history major with a boyish grin, endless charm and an eye for the missing jhumki… and more. It’s a tender, witty, and disarmingly honest reminder that love often arrives like a local train—noisy, unpredictable, but right on time. Krishna mentions, “Basu Chatterjee’s Rajnigandha (1974) has been a major reference point for us. We’ve drawn deeply from his character-first storytelling. Yet, it’s the pulse of Bombay—its public spaces, college corridors, and the fleeting strangers we cross paths with—that truly shaped Jhumkewali.”

Opposites attract? Absolutely. Misra as Rekha radiates a woman in control of her poised self, yet falters when love sweeps her off her careful balance. Robinson’s Bindu rarely steps into a morcha for principle alone, yet will traverse absurd lengths just to light a smile on Rekha’s face. In a tender line, Bindu also interrogates, “Have you ever wanted to purchase the whole world for a person?” Rekha’s impulse is salvation—she wants to fix the world so the one she loves can thrive inside it. Bindu’s impulse is preservation through joy—they’d rather sell the entire world to sustain happiness for the one they adore. Misra and Robinson radiate a chemistry that is at once naive and piercingly aware—moving through a kaleidoscope of pink and blue lights in the discotheque. Utkarshh Babbar and Sankalp Kapur’s lighting thus brings the visually vibrant cityscape and the internal worlds of Rekha and Bindu to life.

Jhumkewali is both memory and mirror: the play transports one to the 70s, even if they’ve never personally witnessed the era. Fashion oscillated between traditional Indian silhouettes, vibrant filmy allure and fragments of Western experimentation, while globalisation remained an aspiration. Riya Rokade‘s costumes for Jhumkewali accurately represent that blend. Bindu perfectly captures this delicate balancing act—a pant-shirt concealed under a sari. Meanwhile, Rekha’s polka-dot dress boldly announces her full-throttle, Bollywood-style self-expression.

As they navigate life together to make their first date happen, they eventually show up in what makes them feel most beautiful, simply to impress the one they love, roses in hand. The play lingers heavily on the split-second moments to touch up lipstick or smooth a stray hair in a very familiar manner that lovers do in anticipation, before seeing one another. It’s adorable, funny and loaded with emotion all at once.

The world of Jhumkewali , designed by Srishti Vaideeswaran is pleasantly bathed in hues of pinks, blues, browns and yellows, wherein whimsy coexists with rustic charm. This is not to say that their love story isn’t political, because they are, in fact, surrounded by unrest. The emotional lives of both Bindu and Rekha are never fully private, always interrupted by the external—family, ideology, the city itself. And yet, these interruptions become part of the choreography, lending humour and grit that keeps the audience tethered. There’s a subtle politics in their interactions too: the playful power of agency, the flirtation that’s both innocent and revolutionary at a time when even glances carried risk. Rekha, the youngest in a house ruled by three elder brothers and cushioned by stability, moves through this world with a daring confidence that flirts with rebellion. Misra says, “Whether it’s joining the women’s union, hanging out with Bindu, or studying what she loves, Rekha goes after what she cares about, no matter the consequences. She’s so young but has a kind of determination that I and I think many of us hope to have.”

Bindu, the only-child of migrant shopkeepers, carries caution in their bones—their initial reserve and reluctance to step into marches and unions standing in sharp contrast to Rekha. This tension between inherited security and precarious independence leads to larger questions about class, belonging, and agency in the city’s chaos. Who gets to claim space, and at what cost? Robinson emphasises, “If Bindu lived in contemporary Mumbai, the confidants once found in the audience would now exist in chosen families, group chats, and quiet corners of the internet. Bindu would still belong in the in betweens of languages, worlds and binaries. This time, they’d know those in-betweens were home.”

Bhansali recounted that the story’s first spark came from a deceptively simple question: “When do you think they started selling jhumkas on the train for the first time?” The play offers a delicate assertion and exploration of the idea that the first person to sell jhumkas on the train must have been a woman in love. Lesbians, in particular, have historically pushed against limits, crafting worlds of connection and creativity simply to answer the call of love, proving that desire itself can be transformative, and unexpectedly inventive.

Although Jhumkewali honours the struggles queer elders have faced, the play doesn’t dwell on the persistent challenges that have defined queer experiences in larger media. Instead, it focuses on the small moments of joy—the effort one makes to be happy and to bring happiness to a loved one, even if it means negotiating with the world for those fleeting moments and fragile havens of contentment. This intimate two-character play thus unfolds like a secret whispered into the audience’s ears, the actors weaving through the crowd with a casual audacity that blurs stage and spectator, daring viewers to confront closeness, desire, and vulnerability, and making their love story almost a tactile, sensory celebration.

Directors Krishna & Singhal do not romanticise queer secrecy nor villainise it. Instead, the play’s gaze captures the quiet ache of women who loved in the shadows long before they had a vocabulary for it. How many Rekhas and Bindus, who once looked over their shoulders, dared to look back at each other? The jhumki, lost and found, thus becomes emblematic of everything women have misplaced in history—freedom, expression, and sometimes, each other. Rekha and Bindu’s choices and hesitations speak not only to gendered expectations, but to the fragile architecture of solidarity itself, leaving us unsettled, intrigued, and acutely aware of what still lies unspoken. Through it all, a rainbow beam of love pierces through the shadows in the form of their persistent bond. As Jhumkewali continues touring in cities like Mumbai and Pune, their journey proves to be one worth celebrating, sharing and talking about. It sparkles—whether watched on a date or alone, with memorable protagonists, witty (sometimes corny) dialogues and an earnest, beating heart.