Bhagat Singh was born on September 28, 1907 and is deemed an extremely influential force in the Indian freedom struggle movement.

Singh’s bravery and sacrifice has made him a memorable figure in media and cultural memory inspiring various films, songs and plays.

On his birth anniversary today, several of his cinematic adaptations are discussed in this piece.

India remembers Bhagat Singh—whose legend has outlived entire regimes as not merely a historical figure anymore but a national shorthand: the tilted felt hat, the fierce moustache and the final march to the gallows. Over the decades, the young revolutionary executed in 1931 at just twenty three, has been painted, sung, staged, and most insistently filmed into immortality. In fact, no other freedom fighter has enjoyed such a prolific cinematic career. He has been reincarnated in films, plays, songs, and documentaries.

In a country that heavily digests history through screens, the question has never been whether he should be portrayed, but how: patriot, socialist, atheist or romantic hero? On his birth anniversary, it feels fitting to ask: what has cinema really done with Singh, and why does he keep returning on screen in a country that is increasingly divided on what dissent even looks like? And yet, each new film or song that dares to summon him reveals less about the man himself and more about India trying to claim him at that moment.

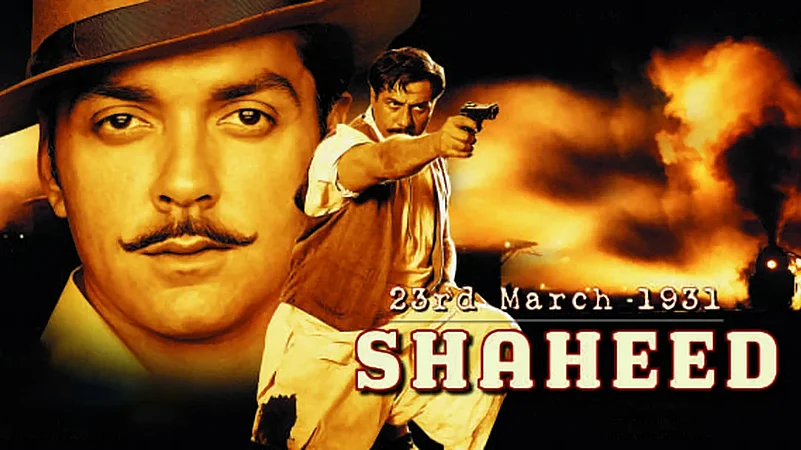

Shaheed (1965), a black-and-white film starring Manoj Kumar, gave audiences a devotional Singh, a hero polished for a post-independence India craving nationalist icons. Songs like “Mera Rang De Basanti Chola” cemented him as a melodic, martial, memorable symbol. The Marxist and atheist Singh, whose essays advocated for radical social change, was barely represented here. But the audience didn’t mind. Cinema was nation-building, not iconoclastic sociology.

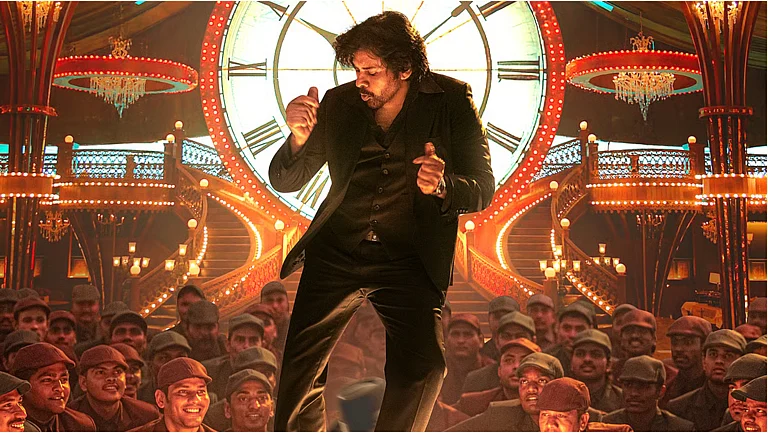

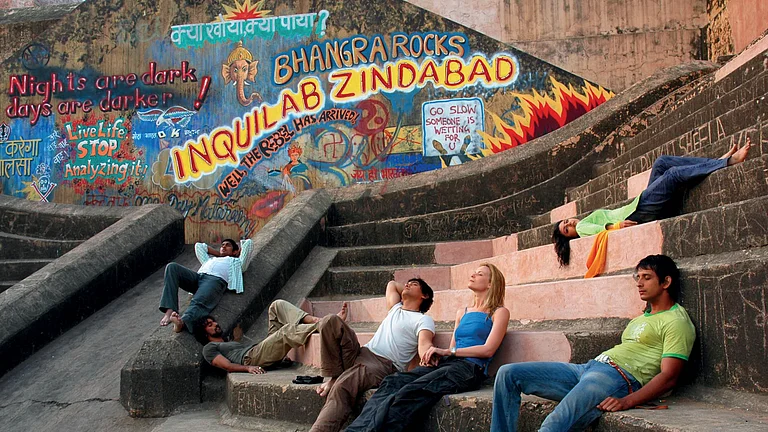

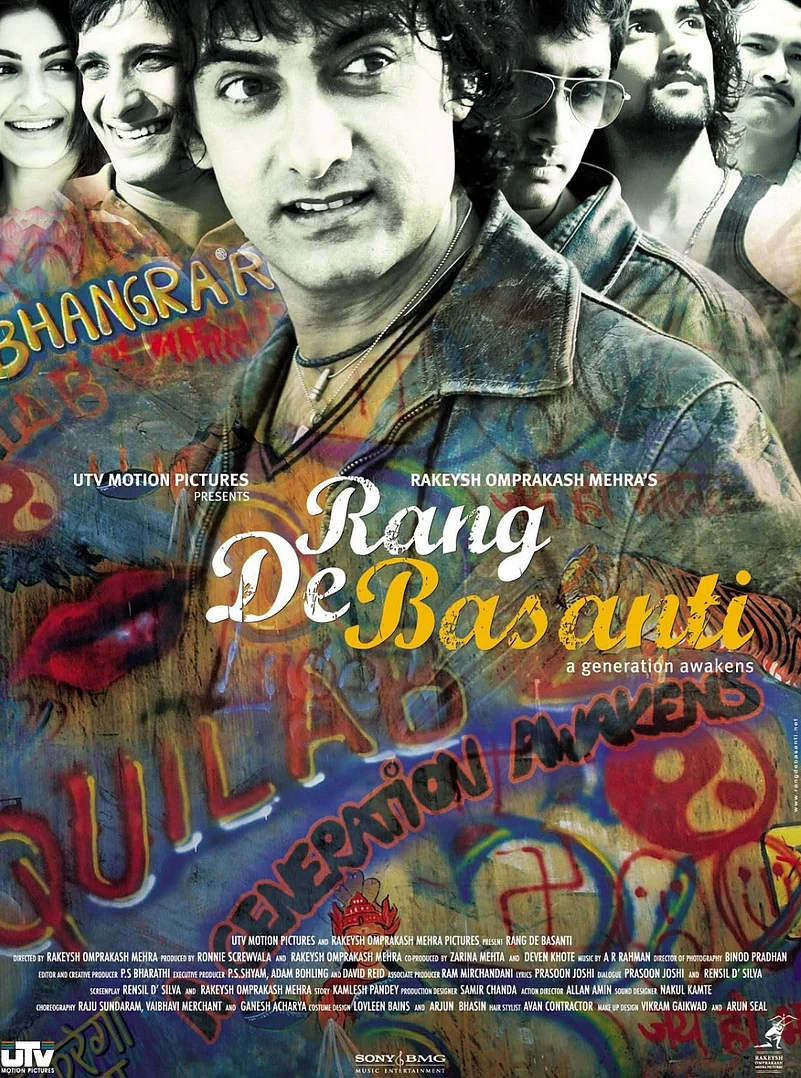

Fast forward to 2002: three films about him premiered in cinema halls that year. The Legend of Bhagat Singh (2002) tried leaning into historical grounding, with Ajay Devgn brooding through Rahman’s stirring score. Critics liked it and it also embodied a certain seriousness. Although 23rd March 1931: Shaheed (2002), starring Bobby Deol, prioritised melodrama first before history, leaving the premise in muddled waters. Then there was Shaheed-E-Azam (2002), with Sonu Sood, smaller, scrappier, authentic-seeming, but swallowed alive by the other two. Then came the most memorable Rang De Basanti (2006) which placed Singh’s courage amidst Delhi students’ restless protests and friendships, inheriting his spirit. Past and present collide, asking whether rebellion is inherited or earned.

Cinema never settled the question of what Singh really was, and probably never will. Films may have given him a face, but music gave him a voice. “Mera Rang De Basanti Chola,” first heard in Shaheed (1965), still surfaces at protests, vigils, and college festivals. Other songs—“Sarfaroshi Ki Tamanna” or “Pagdi Sambhal Jatta”—predate the screen, but cinema amplified them far beyond, so much so that they’re embedded in cultural memory decades later. They perform the double duty of mourning and mobilisation and they travel fast. The soundtrack, in a sense, becomes the medium where the martyr refuses to remain silent.

While commercial films compromise to survive censorship or mass appeal, street theatre keeps Singh dangerous, argumentative, and alive. The medium itself becomes political: the audience is close enough to confront him, and by extension, to confront their own complacency. Ayaz Khan’s Bhagat Singh Ki Wapasi imagines him visiting today’s India, often mocking politicians and questioning contemporary apathy. Theatre’s advantage lies in its proximity. The actor becomes more than a historical figure; he becomes an interlocutor, asking: “Are you brave enough to question authority today?”

For filmmakers seeking unvarnished truth, documentaries have been the only venue. Anand Patwardhan’s In Memory of Friends / Una Mitran Di Yaad Pyaari (1990) dissected the ways different groups—state, separatists, leftists—try to claim him. Here, Singh is never just a historical figure; he is a battlefield over meaning. Gauhar Raza’s Inqilab (2008) went further, reviving the socialist and secular voice of Singh hidden under patriotic hymnals. The documentary is more about the ideas than the dramatics: atheism, socialism, radical critique. It is difficult viewing for those expecting palatable patriotism. Even remembering Singh in his full radicalism is, ironically, an act of dissent.

Why does Singh, more than any other revolutionary, keep being resurrected? Youthful radicalism is another reason: he appeals viscerally to generations that feel suffocated, offering courage that is both aspirational and performative. His essays on socialism and atheism continue to unsettle and provoke thought, reminding us that rebellion is always more than just spectacle. But here is the provocative question: can films still carry dissent? Cinema reaches millions; a song or scene can spread faster than any manifesto. Yet, today’s mainstream films are expensive, heavily scrutinised, and politically fraught. Singh the atheist, the Marxist, the real firebrand—is not likely to survive the censors. It is probably why theatre, documentaries, and digital shorts are now crucial. They are the rebel spaces. In a fractured India, politicians drape him in tricolour quotes while ignoring his ideology. Ordinary citizens chant, hum, and revere him as shorthand for sacrifice. His multiplicity is a weapon and a vulnerability—everywhere, yet never fully whole. Perhaps the most faithful tribute is that his afterlife is untameable.

On his 118th birth anniversary, Singh continues to be celebrated on screens, stages, songs, streets—caught between the definitions of martyr and thinker, patriot and radical, spectacle and symbol. His constant resurrection reveals what India wants from its heroes, what it fears in its radicals, and what it dares to dream. Singh survives not in a single definitive image, but in his refusal to be finalised. Moving, contested, restless, inconvenient, Singh remains rebellion personified.