Summary of this article

Veteran actor Amrish Puri passed away on January 12, 2005 at the age of 72.

He agreed to work in Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge because he had seen Aditya Chopra grow up before him.

The house of the man who played black-hearted characters with complete conviction on screen, exuded an aura that was pure.

Visualise this, a scene straight from real life. A friend’s son, who is in his early twenties, is preparing to follow in the footsteps of his father, a well-known Bollywood filmmaker. He wants Amrish Puri for a pivotal role in his film. Since the veteran actor is fond of the boy, who has literally grown up in front of his eyes, he invites him home for a narration.

“Adi sir wasn’t carrying a script, but he knew every character by heart and enacted all of them with different voice modulations,” Puri’s grandson, Vardhan, an actor himself, recounts in my book, Bad Men: Bollywood’s Iconic Villains (2025).

I can vividly imagine Aditya Chopra sketching out the story of Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), a transcontinental love story that he had written, playing out Raj and his happy-go-lucky ‘Pops’ (Dharamvir Malhotra), Simran and her dictatorial ‘Bauji’ (Chaudhary Baldev Singh), her mother Lajjoji and her younger sister Chutki (Rajeshwari), her fiancé Kuljeet and his sister Preeti, among many other characters who populated this family drama, to a rapt audience.

Puri did not ask a single question, in fact, he did not utter a single word all through the narration. Yash Chopra’s son, perhaps a little unnerved by his silence, told him that the role of Chaudhary Baldev Singh had been written with him in mind and if he didn’t do it, Aditya swore, he wouldn’t make the film.

“With tears in his eyes, Dadu told him that he would love to be a part of his directorial debut,” Vardhan shares and you are immediately transported to that iconic last scene where, after the confrontation with Kuljeet which leaves him bloodied, and an interaction with Simran’s stony-faced bauji which leaves him with a bleeding heart, Raj boards the train with his Pops. As it steams out of the station, Simran desperately tugs on her hand locked in her father’s, trying to convince him that Raj is her life. Hei s unmoved, his eyes locked on the boy who had dared to gatecrash his home and his daughter’s heart. The train picks up speed. Simran’s frenzied attempts to get away are weakening. Love, you sigh, has lost this battle when suddenly, Chaudhury loosens his grip. The move, sudden and unexpected, leaves not just Simran, but even the audience bemused. Acknowledging that no one can love her more than Raj, he urges Simran to leave with his now-famous dialogue. “Jaa Simran jaa, jee le apni zindagi (Go Simran go, live your life).”

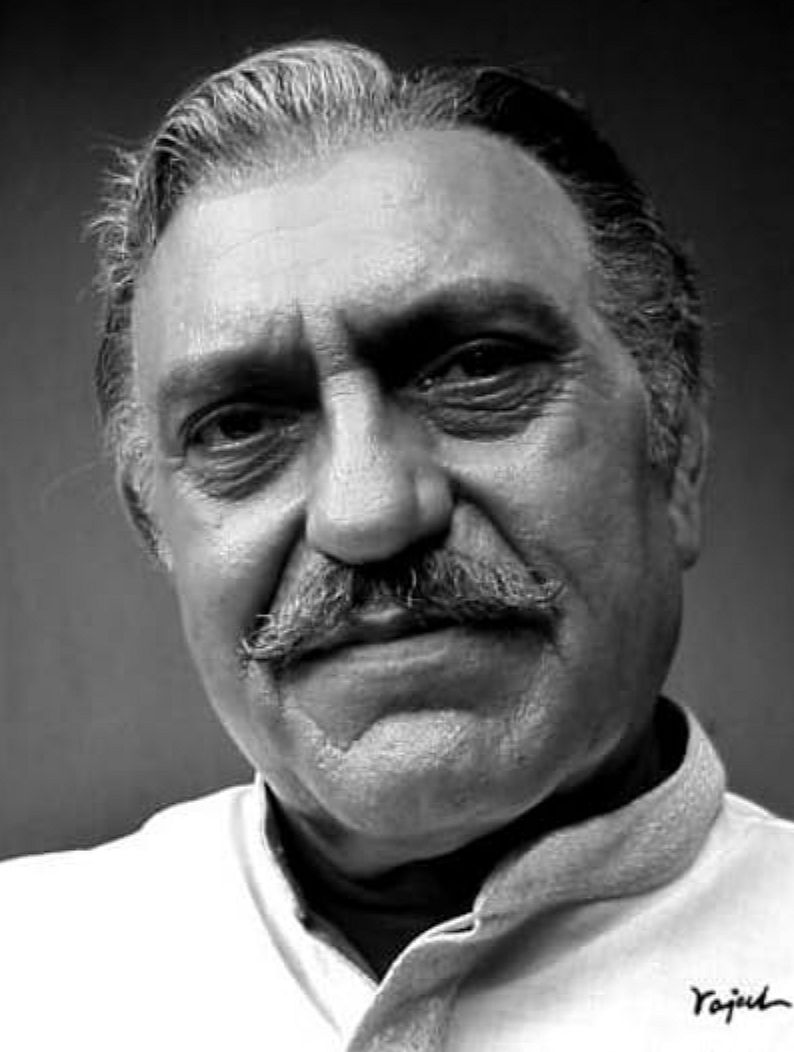

Vardhan goes on to reveal that his grandfather had an animal parallel for all his characters. A hyena was the muse for Mr India’s (1987) Mogambo and a tiger for Ghayal’s (1990) Balwant Rai. Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge’s authoritarian father was modelled on an ageing lion, who may no longer be physically agile, but still commands the same fear and respect. And it was this king of the jungle I went to meet for an interview. I still remember the date, June 22, 1988, since coincidentally, it happened to be his 66th birthday and explained why the house was a forest of flowers.

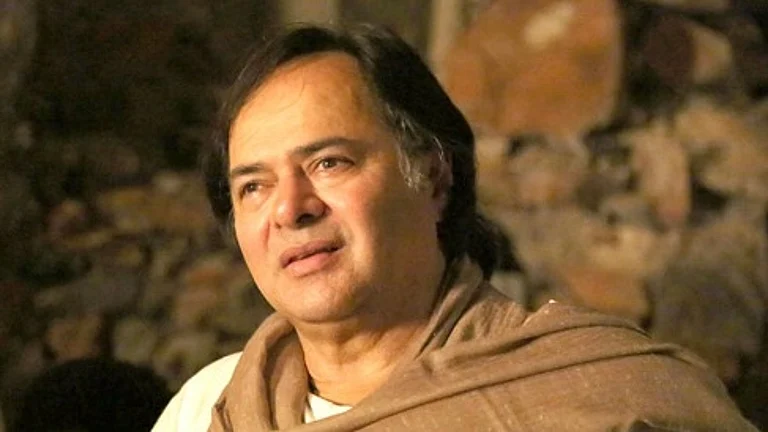

Surprisingly, the home of the man who played black-hearted characters with complete conviction on screen, exuded an aura that was pure. The walls of the Juhu bungalow, also named ‘Vardhan’ because he believed it to be a ‘gift from God’, were painted a pristine white. The curtains billowing at the windows were also white and the floor, polished white marble with streaks of grey. What stood out in this serene oasis was a king-size chair with a matching ottoman, upholstered in crimson, reminiscent of Mogambo’s throne. Puri admitted he had got it designed after the filmi prop and looked larger-than-life as he took his place, but I didn’t hear the familiar maniacal laugh which has sent chills down every spine. The hyena didn’t even roar “Mogambo khush hua” (Mogambo is happy), but purred indulgently, like a domesticated Persian cat over my close resemblance to a favourite niece.

The surprise didn’t end there. I discovered that the philanderer and plunderer of the movies was a pragmatic philosopher in real life, quick to point out that there was no reason to associate him with black only because the colour is often synonymous with an evil mind. “Why focus only on negative connotations when there is so much of grace and grandeur in this great colour too,” he reasoned, adding that even the characters he had played were not all black, all bad. “Even Mogambo has streaks of grey, I tried to make him more interesting than menacing.”

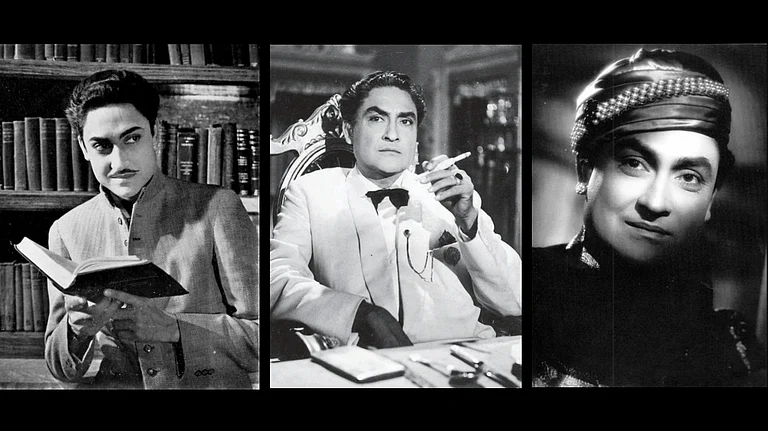

By the time the visit ended, my perception of Puri had changed from the stereotypical bad man—even though a quarter of a century later he did feature in my book on them—to a gentleman. Today, whenever I think of him, I don’t flashback to Mola Ram, the terrifying high priest in Steven Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and The Temple of Doom (1984) who tears out the hearts of his victims, before lowering them into a pit of fire as a sacrifice to the goddess Kali. I see instead the surly judge of Muskurahat (1992), who is taught to smile again by a girl whose paternal responsibility he has taken, even though she is not really his own.

For me, Puri is not Mr India’s terrorist, Mogambo, whose bomb cut short the life of a child and whose missiles could destroy India. Even when he is ruling the underworld, I see the don of Phool Aur Kaante (1991), who will go to any lengths to get his abducted grandson back. Instead of Koyla’s (1997) psychotic Raja Choudhury, who sells young girls into brothels and shoves hot coals into a young boy’s mouth, I would rather remember Chaudhury Balbir Singh of Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge.

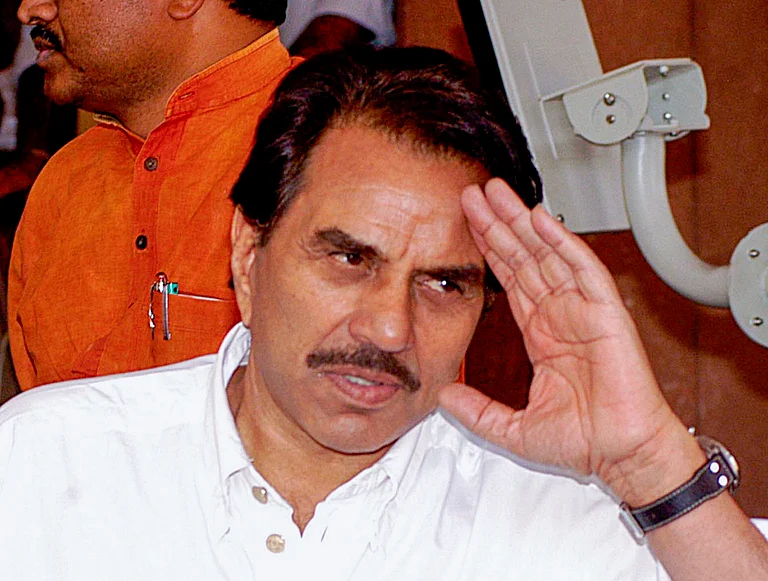

I didn’t meet him again, he went away too soon. While shooting the 2003 action-thriller Jaal: The Trap in Manali, Puri and Sunny Deol, who plays his son, suffered an accident when a motorbike stunt went wrong. Director Guddu Dhanoa, an eyewitness to the incident, recalled Sunny being dragged by the bike for a distance; he escaped with minor injuries. But Puri, who fell to the ground, was in bad shape; he lost a lot of blood and almost lost an eye.

While he made a miraculous recovery eventually, during transfusion, Puri developed a rare blood disease and subsequently started getting headaches, which became more severe with every passing day. But he kept working and by the end of 2004, had completed all his film assignments. Soon after, he fell in his home and suffered a brain haemorrhage.

At 72, his chance of surviving a brain surgery was just around 50 per cent and the family was reluctant to take the gamble. “But Dadu spoke to my parents and aunt, pointing out that having lived his life like a lion, it was getting increasingly difficult to live with the excruciating pain, and insisted on the surgery,” informs Vardhan. Puri died on January 12, 2005, on the operating table, leaving behind the legacy of unforgettable characters and a life lived on his own terms till the very end.