Alireza Khatami's The Things You Kill premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January.

The Turkish psychological thriller follows a professor mentally falling apart in the throes of his mother's death that he suspects as murder

The film is chosen as Canada's Oscar entry

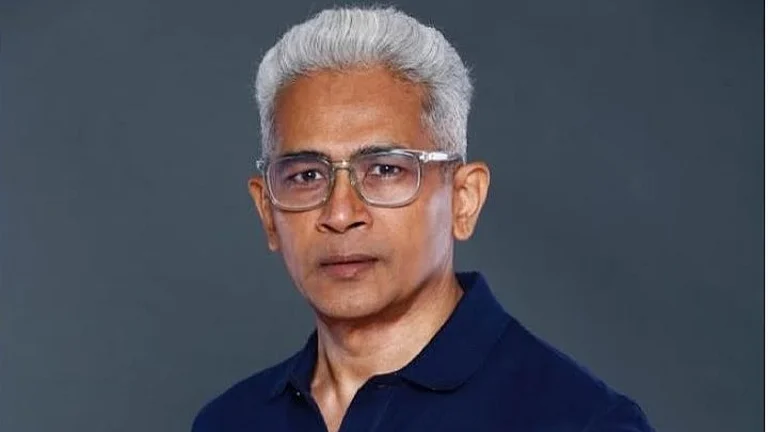

At the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year, Alireza Khatami won the Directing Award for his mind-bending Turkish-language thriller, The Things You Kill, that premiered in the World Cinema Dramatic Competition. With provocative opacity and muddying up of perspective, the tale of a professor unravelling with his mother’s suspicious death gains startling moral ambivalence. Ekin Koç haunts as a man on the precipice of paranoia, lurking loops of patriarchal violence with the film radically redrawing itself at midway mark. Khatami keeps deliciously twisting notions of retribution as his protagonist, Ali, goes through a long night of the soul. When Ali does emerge on the other side, we're left dangling, a pit in the stomach deepening. The film has now been picked to represent Canada in the Best International Feature race at the 98th Academy Awards.

In a paired interaction which Outlook’s Debanjan Dhar joined, Alireza Khatami held forth on ghosts within liberated feminism, crisis-ridden masculinity, flipping usages of mirror and how he decided on shooting a chunk of a pivotal monologue out of focus.

Edited excerpts from the conversation:

Ali is formed and unformed by Western ideas even as he filters those through frameworks back home. But there are key gaps as in also the narrative he initially builds around his father and mother and how that disrupts. It’s almost like two vectors, in between which comes translation. Can you talk a bit about translation and reinterpretation and how it's tied to perspective, narrative, identity?

In developing countries, thinking is often expected to be translation. The one who thinks is the one who can read the West well. In our region of the world, the West is the figure of the father, the colonial, the one who decides for you, sets the rules and regulations, dictates what’s best for you while exploiting you. This problematic notion is very much in order with Spivak’s words when she asks whether the subaltern can speak. I wanted to challenge the notion of translation. In order to build a new framework, you’ve to kill the original and give it birth in a new condition. With the resurrection comes the ghost. Here I recall the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben who speaks of hauntology. The cost of it is to live with the ghost. In the film, you see Ali who returns from the West with these ideas of a liberated feminist. But then he looks at the mirror and it’s terrifying. The process is coming to terms with this complex world.

There’s this disturbing violence which Ali thinks he has overcome because he went abroad. But the violence returns.

In facing the world, Ali finds itself in crisis, masculinity in crisis. For me, the very definition of masculinity is in crisis. It only grounds itself when there’s some overlap with femininity. I’m talking about the philosophy of masculinity. When Ali finally dreams the dreams, he’s grounded. That’s when the ghosts are coming back. The way forward is never through violence. It’s empathy. It’s a difficult act, but the only task.

How did you approach the role and response of women in this densely patriarchal environment? I’m thinking of Ali’s sisters, who have also been privy to an atmosphere of violence, but they are more tempered and compassionate and react very differently than Ali, who’s way more aggravated…

When we talk of patriarchy, everyone and everything is subjected to it. Not even animals are spared. The sisters don’t choose violence. Women have known it far earlier than men that a violent response only exacerbates it further. As traditional as it sounds, to cope with the system, women are the pioneers and messengers of change. Ali learns significantly from them when one says it’s easy to be angry with the father but the real challenge is to live with them.

The crisis reflects the worst possible reactions on women’s bodies, that have always been a battlefield…

The most dangerous thing to a woman is their partner. Men have no way forward but through violence. They do it to their closest ones. It’s a crisis of the patriarchal framework that hasn’t taught men to be vulnerable. Look at the words we use in the English language. The language of achievement is of violence. When we say do well, we say go kill it. We celebrate it through language. This is the contaminated discourse we live through, irrespective of geographical location.

In the film, there are windows, mirrors, looking through a screen. These change the perspective. Can you talk about combining the story, which you’ve drawn from your family background, with choices in cinematography?

In Persian poetry, the metaphor of self is the mirror. It’s a very well-established one that goes back by eight hundred years. The film is about self-negotiation. The moment the subject cracks and he has to look at himself, we go into the mirror. The entire film happens in the mirror. When he finally stands on his feet, he sees the world and we come out of the mirror. The entire second act is frantically inside the mirror, an act of reflection. In the history of cinema, we’ve used the descent into the mirror, but not quite as self-negotiation.

Coming to Ali's monologue, was there pushback while shooting a major part of closeup out of focus and how did you navigate that and decisions like these do you make those while writing itself or later right before shoot?

I didn’t write the scene out of focus. It’s one of the hardest confessions I’ve done and it comes from a personal place. I had no idea how to shoot it. I’d seen The Graduate where the focus puller was a second late. I thought it’s a wonderful tool and I’ll push it thirty seconds. My cinematographer was afraid. My producers insisted to take another shot. But I needed some privacy for the character. Finally, he’s ready to face the questioning as to why he returned home. As he works through a fog of memory and he realizes why he left, we come to focus. It’s the best shot I’ve ever done. In the hands of the wrong actor, it could have gone wrong. Ekin Koç trusted me deeply. He told me he’ll deliver it cold. I love cinema where form and content merge. Who’s doing the performance? Is it the camera or the actor?

How come you chose Turkey?

I went to Iran to shoot the film. Two weeks prior to shoot, the censorship office withdrew permission. They wanted me to remove the scene of the killing of the father. That’s impossible. I’m from a Turkic tribe and I’m an indigenous person from the southwest of Iran. We speak a form of Turkish but it’s different from Turkey. I understand about fifteen to thirty percent. Culturally, Turkey felt the most feasible option. It has wonderful actors and deals with same questions as patriarchy and the killing of women. I didn’t want to do something like an Iranian guy going to Turkey and making it look like Iran. I’ve made films in different languages. I invite the land, here’s my pain, take a piece of it and make it your own. They made the film Turkish.

Now, this film is Canada’s Oscar entry…

This is a wonderful step taken by Canadian film society. Stories don’t have passports. I’m humbled we break this barrier. We had a wonderful reaction from non-white communities. I hope the Oscar becomes more and more about the art of filmmaking. I love that quote by the American war photographer, James Nachtwey, “every story doesn’t have to sell something. There’s also a time to give”. I’m deeply humbled by the selection.

You expect the film to head in a certain way and this film delivers such a bold jolt. I was wondering, while writing, how much of the expectations incumbent on your being an Iranian-Canadian filmmaker weigh in? Can you escape that during incubation or do you actively seek to challenge and take what you can with those pre-set expectations?

It weighs on me all the time! There’s an unimaginable pressure on the cultural side that I have to tell an Iranian story. Festivals constantly try to make you the agent of their policies. The West embraces any film subtly Islamophobic or that questioning the Islamic Republic of Iran to show their moral superiority. What about the genocide, the atrocities on Palestine they have been supporting for the past two years? I’ve zero respect for what Cannes and Berlin did to the Palestinians. Suddenly, Cannes is like they aren’t political. Wasn’t it when Jafar Panahi went to jail, or during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine? When it comes to Palestinians, they’re non-political. This will be a stain on the history of those festivals.

You’ve been invested in this film for eight years. What does that expanse of time do to your writing? Do you just keep rewriting and tinkering with the script?

I have to find the core structure of the script. Once the script is in the hands of people who will raise finances for its making, I start to rewrite. Personally, rewriting never ends until you’re on set. I do an entire rewrite as per locations. I reworked the entire garden scenario. Once I cast, I rewrite.

Are you living in Canada now? Do you go back to Iran?

I’ve been outside Iran for many years. In the past twenty-one years, I’ve visited once. These are choices you make in life. Wherever I reside, criticism of policies affects life.

Are you working on something now?

I’ve been consumed by the Oscar campaign but I’m developing my first English-language feature to be shot in Canada. That’s another challenging storytelling adventure.