“I read in the newspaper that some society lady in Mumbai commented that our Indian athletes go to the Olympics to take selfies and eat free food, only to return empty-handed...without medals,” says Dulal Karmakar, shaking his head disapprovingly. He is sitting in his drawing room at Abhay Nagar, a lower-middle-class neighbourhood in Tripura’s capital Agartala. His daughter, 23-year-old Dipa Karmakar, made history this year by coming fourth in the women’s vault event in gymnastics at the Olympics, performing the high-risk Produnova vault successfully. “We are all very sad that she missed the bronze by a fraction of a score point but we are not that needy that she has to go to Rio to get free food,” he says. His wife Gouri cuts in to add, “And she is not that much into selfies either. She is very shy about publicity. Once we were out shopping and people recognised her, she just rushed out of the store.”

Dipa’s parents are not well off, but they are too proud to speak about the hardships they faced while bringing up their two daughters, Puja—the elder one, who is a homemaker—and Dipa. Dulal, 59, is a weightlifting coach with the Sports Authority of India and earns a respectable salary now. “We are a little embarrassed by reports saying we are poverty-stricken. It has never happened that I could not put food on the table for my family,” says Gouri. But they say Dipa’s journey to the Olympics has been full of hardships, from lack of funds to inadequate resources. When she started gymnastics at the age of six, Dipa’s first practising vault board was a makeshift apparatus, assembled out of spare parts from an old, unused motorbike. Planets away, literally and every other way, from the state-of-the-art Bannon’s Gymnastix in Houston, Texas, where Simone Biles of the US—that gold-rimmed figure at Rio— started her training also at the age of six.

Cut to the Vivekananda Byamagar in Agartala, Tripura, where Dipa had started her training under Soma Nandi (wife of her current coach Bisheswar Nandi who went to Rio with Dipa) in 1999. The enclosure, part of a local club, was set up as a workout space way back in August 1947. In the mid-sixties, a former Indian army sports instructor, Dalip Singh, was deputed to Agartala to scout for gymnastics talent. He was from a family of farmers in Haryana and had been trained by a Russian gymnast at Patiala’s National Institute of Sports run by SAI. During his visit to Agartala, he married a Manipuri doctor, Sushila Devi, and stayed on in Tripura, having decided to work towards turning the state into the gymnastics capital of India. “In India, you will find that most athletes come from poor families. It gives them alternatives to education, which most of these families cannot afford. Sports at local clubs and gyms are usually free,” says Dr Sushila Devi Singh.

It was Singh who, using his clout with SAI, started importing gymnastic apparatus into the state and opening various gymnastic centres across Tripura. Most of the equipment at Vivekananda Byamagar, the oldest gymnasium of Agartala, is from that era. “There has been virtually no maintenance in the last fifty years or so, even though hundreds of girls and boys from across the city practise at this gym every day,” says Soma Nandi. The sole uneven bar, placed on one side of the large hall, squeaks each time a child—“It cannot support adults,” says an instructor—gets on to it. The only balancing beam shows signs of gathering rust. The ropes of the ring hanging from the ceiling appear to have frayed in parts. Even the large stacks of mattresses piled one on top of the other at a corner of the gym, nestling with a host of other discarded equipment, are in tatters, the blue covers frayed, very much like the paint peeling off the walls. “We don’t even have a foam pit (a boxed area cushioned with foam to absorb shock to the feet when a gymnast lands after performing a vault).” According to Soma, if Dipa could practise the Produnova vault on the foam pit prior to the Olympics, “the girl would have brought home gold.”

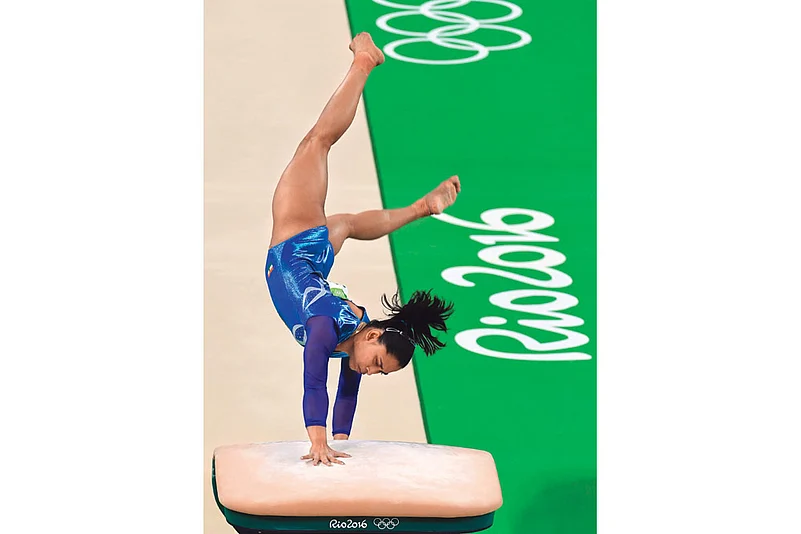

Dipa puts up a fine performance at Rio, 2016

Even the more advanced gym in Agartala (the Netaji Subhash Regional Coaching Centre, where Dipa trained before the Olympics) does not have a foam pit, which is especially critical for the Produnova, which carries the risk of even spinal injury. So, just three months before the Olympics, Dipa had to come to Delhi to practise, where some gyms have foam pits. While she could still count on some support from her family for funds and some backing from the government as her father is with the SAI, a large number of gymnasts and other athletes in Tripura are from extremely poor families. For instance, 15-year-old Ashmita Pal, winner of a cachet of medals including gold, silver and bronze at various gymnastics competitions in India and abroad, who is number two after Dipa and is training for the next Olympics, comes from a very poor family. Her father Arun Pal is a daily-wage labourer, who works at construction sites. Her mother, Shilpi, a domestic help, encouraged her three daughters to join gymnastics in the hope that they will rise above poverty.

Each day she would walk some three km from home to the Vivekananda Gymkhana to drop them off, then get back to cook and do a host of other household chores, working at other houses in between, and again return to the gym to pick them up. “But we could not afford to give them the kind of food that is required to build body and strength. The elder two dropped out and only Ashmita had the grit and determination to remain,” says Shilpi. At her home—a shanty in the back of a slum surrounded by putrid open drains, Ashmita keeps her medals in a covered steel bowl. “I am inspired by Dipa didi,” she says. “If she can do it, I can too. I also want to help my parents by being financially independent.” Her father is working an extra shift to provide for her eggs, fish, meat and some Horlicks, a rarity for their home.

Like Ashmita, most of the other children at the Vivekananda Byamagar are from poor families. Purnima Debnath, 16, is the daughter of a rickshaw-puller. Priyanka Dasgupta, 15, and Rishita Saga, 12, are daughters of drivers. “Not all of them will make it big, of course,” says Banasree Debnath, a coach at the training centre. “Their parents will be content if they can at least land a job with this training.” Purnima Debnath agrees: “I know my parents don’t have much money. So I want to help them by becoming a sports trainer.” Everyone in Agartala is hoping Dipa’s performance in the Olympics now, and the applause she has got from everyone in India and abroad, will change the fate of others like her.

By Dola Mitra in Agartala