If the Karnataka elections were a movie script, the twist in the tale was timed just about right. The storyline, well, was a mash-up of two previous elections in the state: the BJP running out of gas agonisingly short of the finish line, just like it happened in 2008. And, the Janata Dal (Secular) nestling snugly in the middle of the power game, again back to 2004.

Here’s the story so far: Raj Bhavan has given the BJP 15 days to prove it has a majority—the party has only 104 seats out of 222 seats where elections were held. So, the thorny path ahead, as previous experiments with hung assemblies suggest, is strewn with the possibilities of ‘resort politics’, constitutional conundrums and ‘Operation Lotus’, which is the local slang for engineering defections. The JD(S)-Congress combine, which is safely over the halfway mark with 117 seats and has staked claim to form a government, is fuming. The battle for Karnataka is wide open and turning nasty.

If the BJP could stitch up coalitions in Goa and elsewhere despite being a minority, why is it objecting to it in Karnataka, is the question the JD(S)-Congress camp is asking. “We have to protect our MLAs because they (BJP) are capable of doing anything. Do you think we want to sit in a resort because we haven’t any other work,” asks H.D. Kumaraswamy, the JD(S) chief ministerial candidate, who has accused the BJP of luring partymen with huge money. “We’ll face things as they come.” The BJP, on its part, maintains that poaching and horse-trading aren’t its business. “It is what the Congress and JD(S) are famous for,” counters the BJP’s Prakash Javadekar, denying the allegations. But the BJP didn’t explain how it will get the numbers it currently lacks.

Kumaraswamy had, at a press conference on Wednesday, explained that his decision to go with the Congress, in a way, corrects his one-time dalliance with the BJP (in 2006) and proves his party’s secular identity. “I think I’ve got a chance now to erase the black mark on my father’s political career because of my previous act (of going with BJP). So, I’ve decided to go with the Congress,” he told reporters.

Kumaraswamy, 58, went on to say that the governor has received his claim to form a government. “We have given a list of 117 legislators with their signatures to him,” he added.

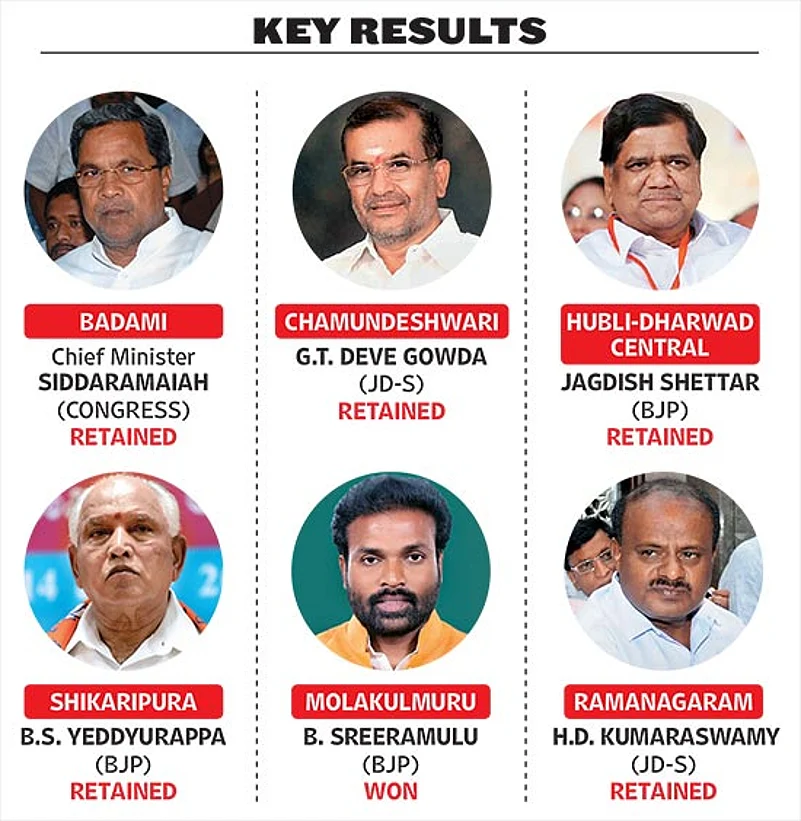

The Congress and JD(S) had fought elections as bitter rivals. (Recall Rahul Gandhi’s jibe calling it the B team of the BJP.) But it appears the Congress had Plan B already worked out, seeing that it deployed seniors Ghulam Nabi Azad and Ashok Gehlot a day before votes were counted. When it became clear that the BJP would fall short of majority, the Congress, with uncharacteristic speed, offered JD(S) support to form government. And so, outgoing chief minister Siddaramaiah and the JD(S) chief ministerial candidate H.D. Kumaraswamy—whose mutual dislike for each other is otherwise a subplot of Karnataka politics—came together to face the cameras. The JD(S), out of power for a decade, won 37 seats, thanks to a Vokkaliga consolidation in south Karnataka, while its alliance partner Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) pocketed one seat.

Siddaramaiah, 69, was defending the Congress’ last big state in the south and staring—as Prime Minister Narendra Modi taunted in his poll campaign—at the prospect of his party being reduced to PPP (Punjab-Pondicherry Parivar). Going into the election, the odds for his party were formidable: fighting on one side the fearsome BJP war machine and, on the other, the weight of history. The Karnataka voter hasn’t been kind to a sitting CM or ruling party in over three decades.

But the Karnataka verdict actually shows how the BJP has recouped from a splintered party unit it was in 2013 and looks more like the brawny outfit it was in Karnataka a decade ago. Even though the Congress got more votes (38 per cent), the BJP’s 36.2 per cent slice of the pie won it more seats.

H.D. Kumaraswamy (2nd from left) greets G. Parameshwara of Congress on May 16

“We didn’t lose a region, we didn’t lose any votebank. But here and there we lost some seats that we could have won,” says a senior BJP functionary. The BJP’s big wins came in coastal and central Karnataka, where it swept through seven districts by winning 37 out of 45 seats in a region where Hindutva and Lingayat sentiment are strong. Then, of course, the booster dose by the PM, whose whirlwind campaign in the final ten days to the election, many reckon, did the trick. “If it weren’t for Modi’s campaign, the BJP wouldn’t have got so many seats,” rues a JD(S) supporter outside former PM H.D. Deve Gowda’s residence in Bangalore where a crowd was swelling by evening on Tuesday, even as the crackers at the BJP’s office in another part of town fell silent.

Many would agree with that. To begin with, says political analyst Sandeep Shastri, there was sharp polarisation among voters between the Siddaramaiah government and the Modi regime at the Centre, but the anti-Congress votes appear to have gravitated to the BJP after Modi entered the fray. “Our study shows that as on April 30, there was something like a 5 percentage point lead the Congress enjoyed over the BJP. From May 1 to 12, that steeply dropped—to one-and-a-half per cent,” he says. This squeezing of the lead, Shastri believes, was because of the PM’s 20-plus rallies.

Add to that the intense grassroots reach of the BJP and RSS cadres. At least 6 lakh people had been deployed for booth-level work across the state, says the BJP functionary. “Even on polling day, we were able to contact many of them,” he says. So the land, as he put it, “was tilled and ready for sowing”. “Modi came and sowed. It wasn’t like it was barren land where he came and did magic,” he says.

The last Karnataka CM to return to power after a full term (in 1978) was the late D. Devaraj Urs, whom Siddaramaiah looks up to as a role model. Like Urs, Siddaramaiah was relying on the backward class-Dalit voters along with minorities to replicate that feat, besides a slew of welfare schemes his government had implemented. “The first thing is that the dominant castes have dominated Karnataka’s politics,” says Harish Ramaswamy who teaches political science at Karnatak University in Dharwad, pointing to how the Lingayats backed the BJP and the Vokkaligas in the south stayed with the JD(S). Experts say the BJP’s seat tally in the Lingayat heartland suggests that Siddaramaiah’s gambit to split the community’s vote by offering them minority-religion status has backfired. As proof, they point out that several Lingayat ministers at the forefront of the cause have lost their seats.

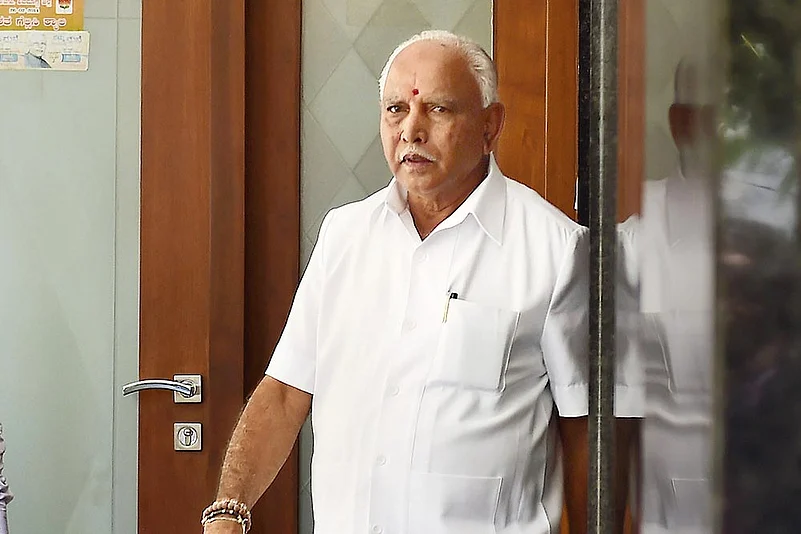

“The Lingayat factor has very badly backfired on the Congress,” reckons Shastri, who thinks the Congress lost—on a comparison with the 2013 results—whatever little support it had among the community. A Congress leader, however, offers a counter-view, saying the issue stemmed Lingayat consolidation to a large extent. “It created some kind of stumbling block for a high-speed vehicle,” says this person. He’s of course referring to B.S. Yeddyurappa, the BJP’s 75-year-old chief ministerial candidate who holds enormous clout among the Lingayat community. Otherwise, there would have been a wave in favour of Yeddyurappa, he admits.

Still, the Congress did reasonably well in the Hyderabad-Karnataka region in the northeast, which has a Lingayat presence, and especially so in Bellary district where it was up against B. Sreeramulu, a popular leader of the Valmiki Nayaka scheduled tribe, and the Reddy brothers. In Bangalore, where the BJP expected a higher tally, the Congress held on firmly.

Of course, anger at sitting MLAs has been the undercurrent in many places across the state. For instance, in one constituency in Raichur district, where the JD(S) replaced the Congress, the argument that one heard was, “Siddaramaiah has done work, but what has the local MLA done for us?” Given that 10 ministers lost their seats, the message was clear, says commentator Narendar Pani. “It’s an anti-incumbency vote.”

By Ajay Sukumaran in Bangalore