Summary of this article

UAPA in J&K often results in long jail terms before trial, with bail nearly impossible.

Such cases rely heavily on confessions, digital records, or associations.

Families face stigma, financial loss, and trauma, even in cases ending in acquittal.

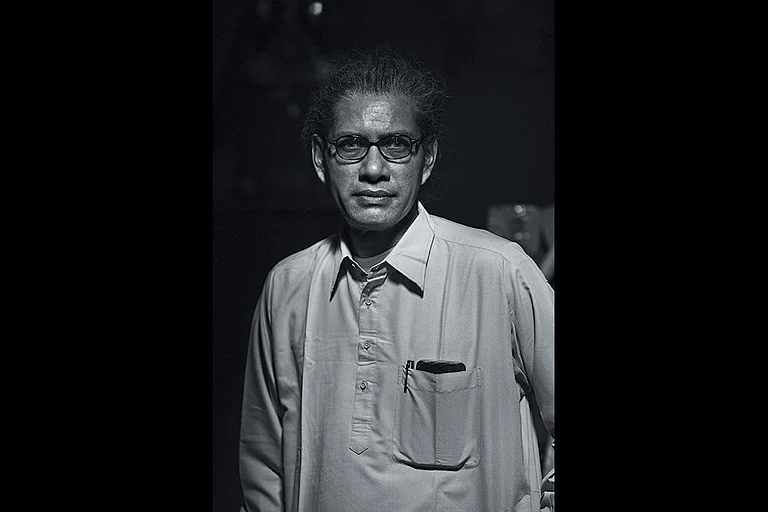

Aadil Pandit is a human rights lawyer practising in Jammu and Kashmir who has represented more than 200 accused under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA). He comes from a family of lawyers and has spent years navigating some of the region’s most complex and politically sensitive cases, where prolonged incarceration and delayed trials have become routine.

Pandit’s work includes cases involving ordinary citizens as well as activists and journalists. He represented journalist Asif Sultan, who faced charges under UAPA sections 16, 18 and 39, along with Ranbir Penal Code (RPC) sections 302 and 120B, and was granted bail only after five years of detention.

Another case from Anantnag involved Shazia Yaqoob Shah, who was detained in two cases registered at Shaheed Gunj and Batamaloo police stations under UAPA sections 16, 18, 19 and 39, and RPC section 302, and got a bail later.

A PhD scholar was arrested in 2023 for an article he wrote in 2011, and was granted bail after nearly three years in custody. Pandit has also defended Bashir Ahmed Mir, Mukhtar Husain Shah, Faisal Ganie, Ajaiz Lone, Bilal Ahmad Malla and Danish Wani, who were acquitted or released after spending more than five years behind bars.

In an interview with Outlook, he explains how under the UAPA, the legal process itself has become the punishment.

UAPA In J&K: A Tide Of Arrests

The number of arrests under UAPA in J&K has grown a lot in recent years. What worries me is not just the number of cases, but the way people are being accused. Many are charged based on who they know, what they think, or what they post online, rather than any actual violent act.

In practice, UAPA is now often used as a preventive or pre-emptive measure. People are arrested to stop possible threats, even if no concrete crime has been committed.

This makes it hard to protect the rights of the accused, because they are being punished based on suspicion or association, not proven wrongdoing.

Jammu & Kashmir occupies a unique constitutional and security position shaped by prolonged militancy and counter-insurgency. This has led to an intensified security framework where the threshold for perceiving threats to sovereignty or public order is significantly lower than elsewhere. As a result, conduct ordinarily falling under the IPC, such as speech, online activity, or alleged association, is frequently reframed as a national security offence, leading to the invocation of UAPA even in the absence of overt terrorist acts.

UAPA’s exceptional procedural advantages like extended custody, prolonged investigation periods, and stringent bail restrictions under Section 43D(5), combined with institutional pressure to adopt a zero-tolerance approach, make it a preferred prosecutorial tool.

Consequently, UAPA is often employed as a preventive measure rather than a post-offence response, explaining its disproportionate application in J&K.

The Bail Barrier

The definitions of unlawful activity and terrorist act under UAPA are extremely broad, allowing prosecution based on intent, association or ideology even without proof of actual violence.

UAPA also gives investigating agencies more time up to 180 days to complete investigation, which delays default bail and results in long periods of custody without trial.

The bail provisions are especially harsh. Under Section 43D(5), bail can be denied if the court finds the allegations to be prima facie true, without examining the evidence in detail. This reverses the normal rule where bail is granted and detention is an exception.

Trials in J&K under UAPA often rely on confessions before police, digital or intelligence-based material and non-availability of judges. These features make UAPA operate more like a preventive detention law, where people remain in jail long before guilt is finally decided.

Normally, you are innocent until proven guilty, and getting bail is your right. Under UAPA, if a judge thinks the police’s accusations look true at first, they must deny bail. The problem is that at this early stage, the judge is generally reframing itself to check if the evidence is actually good or if the witnesses are lying. The court basically has to take the police word for it. This forces the accused person to prove they are innocent before the trial even starts, which is nearly impossible without a full investigation.

In the end, this makes jail feel like a punishment for a crime that hasn’t been proven yet.

Slow Machinery Of Trials

UAPA cases in J&K move extremely slowly. Even deciding whether to frame charges can take one to two years, followed by further delay in passing orders. Trials then proceed at a very slow pace, with witnesses appearing over several years due to repeated adjournments.

In many cases, final verdicts come only after five to ten years. Nowadays trend has started in Kashmir to go for confession before judge because the process has now become punishment and conviction is a relief for them.

Procedural safeguards are often treated as formalities due to the security-oriented nature of the law. Documents are frequently supplied late or in parts, affecting the accused’s right to prepare a defence.

Sanction for prosecution is often granted mechanically without proper application of mind. Courts tend to extend remand and investigation periods without strict scrutiny. The use of sealed covers and secret intelligence further limits the defence.

Accused persons under UAPA face serious hurdles beyond ordinary criminal process. The defence often has limited access to evidence, as prosecutions rely on sealed or we can say classified material supplied late or incompletely.

Trials are frequently delayed due to prosecution deliberately not issuing the summons to witnesses because they know fate of their cases they using these tactics to serve their purpose to prolong the detention of accused while the accused remains in custody.

Cases also being relied heavily on confessions before police, digital and circumstantial evidence that is rarely tested at early stage in Kashmir, and statutory sanction is often granted mechanically.

Evidence On Paper

In many UAPA cases, the police rely heavily on confession or disclosure statements or pointing out memos or photo identification in custody made while the accused is in custody. These evidences are legally weak, as such confessions and pointing out memos are not admissible unless they lead to a valid discovery of fact would prove culpable fact against accused. Even then, the recoveries are often poorly supported.

Another common issue is that recoveries are shown to be made at the instance of the accused but without any independent witnesses. In many cases, only police officers support these recoveries, with no proper documents or forensic evidence linking the recovered items to the accused affecting their credibility.

There is also excessive dependence on digital evidence such as call records, mobile data, and social media content. Frequently, this evidence is produced without proper legal certification or clear explanation of how it has been collected, stored, and analysed. Gaps in the chain of custody and lack of forensic transparency are too common.

Many cases are based on mere association, such as alleged contact or ideological links with banned organisations, rather than actual involvement in a terrorist act. This weakens the requirement of proving intention and active participation.

Independent civilian witnesses are usually missing, and the prosecution mostly relies on official witnesses. While this is not illegal it requires stronger proof, which is most of the time lacking.

These cases reflect a move away from evidence-based cases towards suspicion-based cases, leading to long detention without strong proof. Strict judicial scrutiny is essential to protect fair trial and basic criminal justice principles under UAPA.

Lives Shattered

The human cost of UAPA cases goes far beyond the courtroom and is often irreversible. Once a person is booked under UAPA, the entire family suffers. It takes toll of them socially, financially, and psychologically. Families face stigma, isolation, loss of livelihood, and heavy legal expenses, while the accused endures years of uncertainty and incarceration.

For the young accused pursuing education academic careers suffer serious and permanent damage. By the time the accused are eventually acquitted, after spending years in custody, their lives are already disrupted. Careers are destroyed. Families break apart. Children grow up without parental support. And elderly parents may not survive to see justice. In practice, under UAPA, punishment often comes before conviction, exposing a harsh gap between legal principles and human reality

Accused are often kept in jail for years without trial or conviction, leading to severe mental stress, anxiety, and loss of hope. Legally, this amounts to punishment without guilt and undermines the right to personal liberty under Article 21.

Such long detention also weakens public trust in the justice system. Law abiding citizens begin to avoid lawful speech, meetings, or online activity to protect themselves. This creates a climate of fear and self-censorship, affecting not just the accused but society as a whole.

Acquittal Isn’t Freedom

Many accused spend five to ten years in prison and are later declared innocent, but their lives are already ruined. They struggle to find jobs, as employers hesitate despite acquittal, and social stigma continues. Marriages and relationships often break during long incarceration, and reintegration into society becomes very difficult.

Surveillance of police, regularly being asked to appear in police stations, any untoward incident in any part of the valley leads to attendance in police station usually being detained illegally for days and months and also being detained under Public Safety Act (PSA) for two years, without any crime irrespective of circumstances. Even after being cleared by the courts, the label of a UAPA case follows them. These cases show that legal innocence does not always restore dignity, and the social and psychological damage often remains permanent.

Although convictions under UAPA do occur, most of the cases end in acquittal or discharge after the accused has already spent years in jail. Courts often acquit not on technical grounds, but because the prosecution fails to prove the case beyond reasonable doubt and relies on weak or association-based evidence.

Why This Matters

While national security is important, UAPA in J&K is often overused beyond its intended purpose. Meant for serious threats like terrorism, it is sometimes applied too early or without clear evidence, making it routine rather than exceptional.

This overuse undermines public trust in democratic institutions. Communities may feel targeted or fearful instead of protected, and long detentions with delayed trials erode confidence in fairness. Laws meant for extraordinary situations must be applied with restraint to maintain both security and public trust and in justice

International human rights standards stress protecting individual rights even in national security cases. Key principles include proportionality, presumption of innocence, and fair trial rights, such as access to evidence and legal representation.

In Kashmir, these standards guide me to uphold constitutional safeguards in every UAPA case. Even with serious threats, the accused’s fundamental rights must be respected to ensure justice is not compromised.

From my experience defending over 200 UAPA cases in J&K, the hardest part is protecting the accused’s basic rights in an environment dominated by fear and suspicion.

In many cases, public opinion created by selected national media, administrative pressure, and security concerns create a situation where people assume guilt before trial. As a defence lawyer, I have to stand firm on constitutional principles like the presumption of innocence, the right to bail, and fair trial rights, even when it feels like the system is stacked against the accused.

It is challenging because the law is often applied in a way that prioritises security over individual liberty. But from a legal and ethical point of view, ensuring that every person gets a fair chance in court is not optional. It is essential, no matter how difficult the circumstances. The toughest part is defending freedom and fairness when everyone else is focused on suspicion and fear.