Summary of this article

Jaipal Singh was an Adivasi who 100 years ago attained a BA Honours Degree from St John’s College, Oxford University, and went on to became one of India’s most significant yet least recognised founding statesmen.

He was president of the St John’s College Debating Society, was awarded a Hockey Blue for his participation in the University Hockey Team, captained the College Hockey team and later, the Indian Hockey team for the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam.

When he returned to India, he fought for the rights of Adivasi people, famously declaring he was proud to be “Jungli” and that “you cannot teach democracy to the tribal people; you have to learn democratic ways from them,” a fight and message that remains important today.

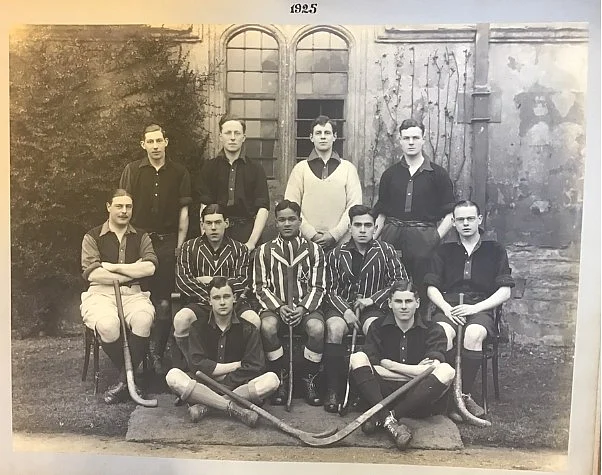

If you visit the archives of St John’s College, Oxford University, as I did last summer with a group of Adivasi scholars based in the UK and Europe, and turn to the years 1924–25, you’ll discover something remarkable. In the photographs of the hockey team and the records of the debating society, a striking figure stands out: a dashing, Indian-looking young man, seated confidently at the centre of the hockey team, of which he was captain. His poised expression, high cheek bones, and knowing smile suggest not just charm, but leadership.

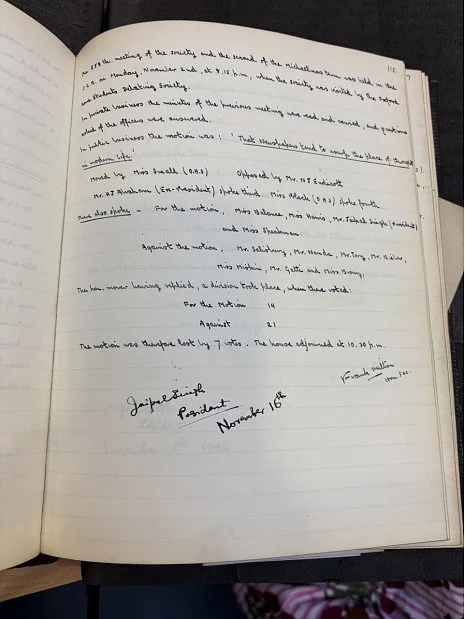

That same year, he not only earned a Blue – an honour given to a sportsman at Oxford University – but also served as secretary of the St John’s College debating society, becoming its president in October 1925. He delivered eloquent welcome speeches to new students, stirred audiences with sharp oratory, and presided over spirited debates on timeless topics such as: “That newspapers tend to usurp the place of thought in modern life”; “That this house deplores the existing public school system”; “That this university stands in urgent need of reform”; and “That the spirit of nationalism is incompatible with world peace.”

From this, you might guess he was reading for a BA Honours in Politics, Philosophy and Economics—a degree often called a ‘passport to power’ for its role in shaping some of the world’s most influential public figures. But it wasn’t just the curriculum that gave it status; it was the kind of people it was said to cultivate—worldly, articulate, intellectually agile individuals with a conviction that they could serve and shape the world.

Though he matriculated under the name Ishwardass (“Servant of God”), he signed the debating society minutes as Jaipal Singh—a name fit for an Indian prince. Which makes it all the more striking to learn that he was not born into aristocracy but came from the remote forest villages of what is now Jharkhand, India. An Adivasi——an aboriginal, an indigenous youth, from a community often counted among the poorest and most vulnerable in the world—had risen to this global stage with dignity, vision, and undeniable presence.

Jaipal Singh would go on to captain India’s first Olympic hockey team to a gold medal in Amsterdam, though he left before the final match. He began as probationer in the Indian Civil Service, the higher civil service of the British Empire in India, which he quit to lead the Olympic team. A lucrative job working for Royal Dutch Shell Group in Calcutta followed from which he returned to the British Colonial Service as a teacher and senior house master of the Prince of Wales College in Achimota, British West Africa. It seems unthinkable today—an aboriginal teaching princes. Yet, when he returned to India in 1935, he became Principal of Rajkumar College in Raipur, where princes were educated and where he was charged with introducing “the ways of the English public school”. From there, Jaipal Singh was appointed colonisation minister and revenue commissioner for the princely state of Bikaner, Rajasthan after serving a short stint as railway minister. Ultimately, he became one of India’s most significant yet least recognised founding statesmen—a powerful voice for the rights of India’s aboriginal people, who today account for more than 100 million people. Fluent in Oxford English, he also spoke Hindi, Bengali, Nagpuria, and his mother tongue, Mundari.

Today, among the Adivasi communities, he is often referred to in reverence as “Marang Gomke”— “The Supreme Leader”. As common among Adivasis, he in fact had many names, depending on the environment in which he found himself. At birth, in 1903, he was named Binand Pahan. Binand was the name of his father’s elder brother and pahan signified that his family had the status of being the spiritual authorities of Takra village, where they lived. For a while he was called Pramod, at school he was admitted as Jaipal, and on baptism he acquired Ishwardass, though now he is most often referred to as Jaipal Singh Munda to signify the name of the tribe into which he was born.

I first came across Jaipal Singh Munda shortly after spending two years (2000–2002) living among the Munda people in a remote forest village in Jharkhand, conducting ethnographic fieldwork for a doctorate in social anthropology at the London School of Economics and Political Science. At that time, just over a century after Jaipal Singh was born, literacy in the community was as low as 10%, and while the people I lived with hadn’t heard of him, his name appeared in the region’s history books. My interest in him deepened when I learnt that a fellow anthropology doctoral scholar and friend at the London School of Economics, Barbara Verardo—who was living among the neighbouring Ho tribes—received a hand-written manuscript from her Italian undergraduate mentor, Professor Enrico Fasana. He, in turn, had been given the pages by Jaipal Singh’s eldest son when they met by chance in Mumbai in the 1970s.

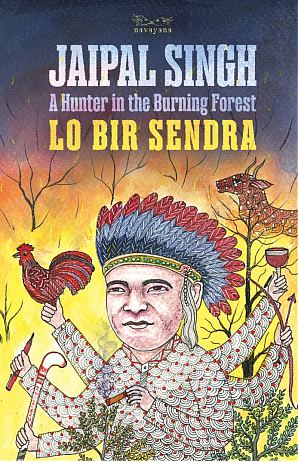

Like a treasured relic, Barbara brought the manuscript back to Jharkhand, and entrusted it to two radical Jesuit priests in the town of Chaibasa—Matthew Areemparampil and Stan Swamy—both lifelong advocates for Adivasi rights and social justice who had established a thriving Tribal Research Institute, so that it could be of use to activists and scholars. The

manuscript was a remarkable collection of Jaipal Singh’s personal reflections and memories, written on a sea voyage from India to England in 1969, the year before he died. Deeply moved by its contents, Stan Swamy edited the script and arranged for its publication in 2004 by the local newspaper, Prabhat Khabar, with the title Lo Bir Sendra—bringing the story full circle, and ultimately placing it in my hands. Thanks to the vision of S Anand at Navayana, in 2025, this precious document has been brought back into circulation.

Over the past two decades, I have read this script—let’s call it a biography—more than four times. Each reading has left me astonished, revealing new layers of meaning and significance. When I first went to live among the Mundas, it was not uncommon for them to run and hide in the forests, on the arrival of outsiders. Their abhorrence and suspicion were rooted in history—repeated experiences of violence at the hands of high-caste police and forest officials who treated them as jungli—wild, savage, barbaric. They were beaten, detained, and systematically marginalised. The Mundas I lived among sought to keep the State at bay.

And yet, here was a Munda who, a century earlier, was not only drinking champagne and whisky with some of the most influential statesmen of the time—he even describes presenting himself to Eleanor Roosevelt—but also influencing them in profound ways.

The role of Christian missionaries among certain sections of the Adivasi communities is essential in understanding this transformation and apparent differences. Missionaries brought more than religion; they introduced formal education and served as intermediaries between the state and the people. At age nine, Jaipal Singh was enrolled at St Paul’s School in Ranchi by his father, where he received an exceptional education. His intellect quickly stood out, and he caught the attention of Canon William Cosgrave, an Irishman serving as Chaplain of St Paul’s Cathedral, Vice-President of the Ranchi Municipality, and Principal of the School. When the Canon returned to England in 1918, he took the young Jaipal with him and enrolled him at St Augustine’s College, Canterbury, with the intention of preparing him for priesthood.

After two terms, the college’s Warden, Bishop Knight, recognised Jaipal Singh’s promise and wrote to Dr James, President of St John’s College, Oxford University, then a centre of religious training for Anglican clergymen, recommending him for admission. At St John’s College, Jaipal Singh noted that he was the only "Asiatic," as Asians were then referred to, but he was nevertheless given a large room in the front quadrangle facing the chapel, a marker of the esteem with which he was being treated.

Jaipal Singh’s education at Oxford was funded by a Hertfordshire scholarship from the bishop and supported by the Forster sisters—wealthy spinsters from Darlington and friends of Canon Cosgrave—who paid his college expenses. Later in life, Jaipal Singh acknowledged that he owed everything to the Canon. It was the Canon’s pivotal intervention that set him on a path into the highest echelons of British and Indian society.

“Undergraduate friendships are lifelong,” Jaipal Singh said. At Oxford University, he befriended many who would go on to shape modern India. He regularly visited the home of Verrier Elwin’s mother on Woodstock Road for tea. Elwin, who began as a missionary, later became an anthropologist who lived among the Adivasis and fiercely advocated for the preservation of their unique cultures and traditions, eventually serving as Nehru’s advisor in the Northeast. The concern Elwin and Singh shared for Adivasi autonomy connected their legacies.

Jaipal Singh's Oxford contemporaries included Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, a fellow at All Souls College, later President of India, and others who became involved in the movement for India’s independence: Lala Lajpat Rai, V. S. Srinivasa Shastri, Annie Besant, C. F. Andrews, George Lansbury, and the writer E. M. Forster.

While the influence of Canon Cosgrave, Oxford University, and these powerful associations cannot be overstated, Jaipal Singh’s own talent was equally vital. Oxford University nurtured his gifts, and in turn, opened many doors. While the debating society honed his political skills, it was his brilliance in sports that made him truly stand out.

Jaipal Singh proudly recalled, “I was called the finest fullback of the century… There was nothing extraordinary in my play. I was a sprinter and could outrun the cumbrous British forwards… One medal leads to all the others. I got colours for football, tennis and rugby. Coming from the Jharkhand jungle, I could have got a cricket Blue. I could see the ball seconds before anybody else. But the first two terms kept me to hockey and in the summer term I couldn’t deny myself serious studies.”

He said, “The inflated publicity of my prowess in hockey proved profitable. I reported about varsity hockey matches in the undergraduate weekly Isis, for which I received five guineas per term. The leading London papers took a fancy to my articles and invited me to report for them at two guineas per report. This brought me eight guineas a week during the hockey season.”

Through sport, Jaipal Singh forged friendships outside the usual undergraduate circles. One of them, John Cecil Masterman—a fellow sportsman—godfathered him, and later became Vice Chancellor of Oxford University.

In the imperial world, sports clubs, high society, and politics were closely intertwined. Upon returning to India, with the Olympic feather now added to his cap even if he left before the final match, Jaipal Singh was invited to lead numerous sports organisations. He served as President of the Delhi Flying Club, the Delhi Hockey Association, the Delhi Football Association, and the Delhi and District Cricket Association. He was a prominent member of the All India Council of Sports and chaired a national committee on sports reform. As manager of the Parliamentary Sports Club, he even organised a cricket match between Prime Minister Nehru’s XI and Vice President Radhakrishnan’s XI—a symbolic event that drew 25,000 spectators and prompted a dinner hosted by the Prime Minister. Jaipal Singh said, ‘the whole event had a great effect on the political atmosphere. It brought together all political parties, and a friendly atmosphere developed in both houses of Parliament.’

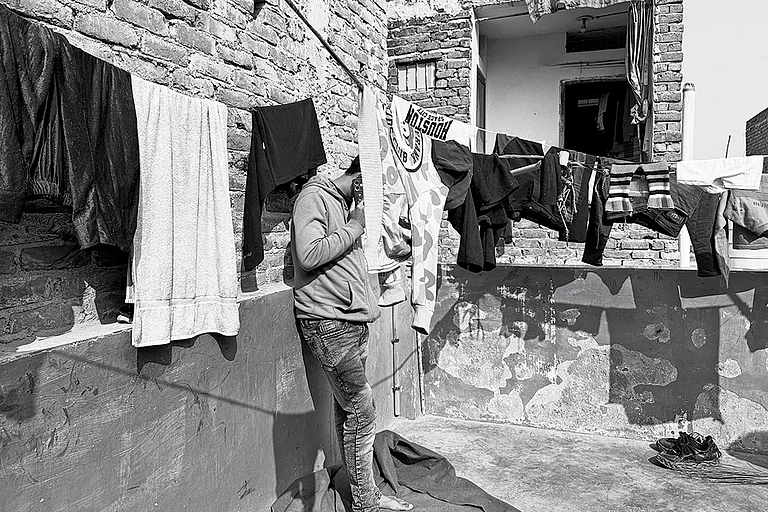

In contrast, the Mundas I lived with—though equally gifted—lacked access to such opportunity. They had no schools of St Paul’s calibre, nor mentors like the Canon who could open the world to them. Despite living atop India’s richest reserves of iron ore, coal, and bauxite, Adivasis in Jharkhand have faced relentless exploitation. Their forests and lands have been plundered by successive waves of outsiders. Thousands were once forced into indentured labour on Assam and Bengal’s tea plantations to produce tea leaves for the British palate; today, just as many migrate to distant cities, working in precarious, low-wage jobs in brick kilns and construction sites.

Their story is not one of individual lack, but systemic exclusion—of a people rich in culture and resources, yet persistently denied the structures that might have allowed more Jaipal Singhs to emerge.

Jaipal Singh saw the devastating impact of this dispossession on his people, and emerged as a fierce advocate for their rights as the original inhabitants—the Aboriginals—of India.

Between December 1946 and January 1950, he played a vital role in the Constituent Assembly, not only demanding reparations on behalf of the Adivasis but also fighting for their enduring autonomy within India. He recognised early on that the end of colonial rule would not automatically end the pervasive exploitation and internal colonisation of the Adivasis by dominant castes and classes in independent India. He fought relentlessly to protect the fundamental right of Adivasis to their land.

Yet, it was not always clear that Jaipal Singh would take this path. By the 1930s, he was well-entrenched in both Indian and British elite circles. He wore fine silk suits, married Tara Mazumdar—a Bengali Brahmin and granddaughter of the Indian National Congress’s founding president – —and stayed at top-tier hotels, country houses and government bungalows, whether it was in Kensington or Delhi.

For their honeymoon, Jaipal and Tara Singh travelled in a first-class coupe to the Adivasi state of Bastar. They spent a fortnight as guests of the British administration, visited the majestic Indravati falls and local markets, one of which he described as “primitive in every sense.” He remarked, with a detached, voyeuristic and seemingly racialised gaze, that, “the Gonds were naked; most of the women had only a couple of leaves to cover their best.” In that moment, he saw them not as kin. Tellingly, none of his own family or kin appear to have been invited to his wedding.

The turning point in Jaipal Singh’s journey back to Jharkhand in the service of the Adivasis came from what may appear to be the most unexpected of sources: British colonial officials. Among them were the Governor of Bihar and the Chief Secretary—specifically Sir Maurice Hallett, an influential figure whom Jaipal Singh had known since childhood, and in whose Bournemouth house he had spent some of his holidays. Jaipal Singh said that in 1938 Hallett invited him to tea at Government House in Patna, Bihar and advised him, “Don’t waste your time with Congressmen. Go to Ranchi. An Adivasi agitation has just started there. You have wandered around the world and you have made a good living. Do something for your people now.”

That same day, Jaipal Singh received a similar message from another towering figure in the colonial administration—Robert Russell, the Chief Secretary of Bihar and the architect of Connaught Place. Russell, too, was an old friend from Jaipal Singh’s childhood. He didn’t just encourage him to lead the Adivasi movement; he also posed the practical questions that such a decision demanded: “Have you sufficient funds to last? There will be no money if you take this up. Where will you stay?” Despite the uncertainties, Jaipal Singh resolved to act, “I decided to do something then in memory of the canon, who had passed away two years ago, in 1936.” Though the elite world he had known would always remain a part of him, even if his marriage eventually collapsed, from that moment on, his path was clear—he would return to his people, and fight for their future.

In Jharkhand, with his worldly experiences, Jaipal Singh quickly became a hero. Local Adivasi leaders invited him to lead the fledgling Adivasi Sabha, which under his leadership grew into the Adivasi Mahasabha (the great Adivasi assembly), and which in 1950 became the Jharkhand Party, as a counter to the Congress Party in the region.

During WW2, Jaipal Singh supported the British war effort: 7,200 Adivasis joined the British Indian Army in both combatant and support roles and he said that, “indebtedness disappeared from Chhota Nagpur” and that many of those who served returned with broader worldviews, strengthening the Adivasi movement.” But of course, as a result, he was “dubbed a traitor to the struggle for national freedom.”

Although the Adivasi Mahasabha lost the 1946 elections, it was strong enough to send Jaipal Singh to the Constituent Assembly as a representative of the Excluded Areas of Bihar. He remained in Parliament until his death in 1970, taking the Adivasi cause to the national stage.

Jaipal Singh fought on many fronts. He championed labour rights forming a union demanding elimination of contractors, proper terms and conditions of work for the Adivasis being displaced for mining and power plants by big corporations and the central government, and for workers having a share and greater say in company affairs. He established a weekly bulletin called the Adivasi Sakam, bringing awareness of the issues that Adivasis faced. Most importantly he fought for the separate state of Jharkhand, to cover all the Adivasi areas of eastern and central India, not only the Chotanagpur Plateau and Santhal Parganas in Bihar but also in the neighbouring regions of the states of Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and West Bengal.

If the elite worlds he had come to know at Oxford became a part of him, even in his days at Oxford, Jaipal Singh had apparently not lost touch with his roots. As he once said, ‘The Adivasi in me never deserted me.” When he spoke for the first time in the Constituent Assembly in December 1946, he declared, ‘I am proud to be a Jungli—that is the name by which we are known in my part of the country.’ This pride, so difficult for most Indians to grasp, was shared by the Mundas I lived with who said they were people of the ‘Jungle Raj’, the jungle kingdom.

While dominant society racialised, disparaged and stigmatised Adivasis as jungle—as wild, savage and barbaric – Jaipal Singh Munda’s life, and the dignity of the people I lived with, reveal not only the truth in Walter Benjamin’s famous insight, ‘There is no document of civilisation which is not at the same time a document of barbarism’, but also that those labelled barbaric may in fact be the most civilized—people from whom we have much to learn.

In that most powerful of Constituent Assembly speeches, Jaipal Singh declared:

“You cannot teach democracy to the tribal people; you have to learn democratic ways from them. They are the most democratic people on earth… What my people require, Sir, is not adequate safeguards… They require protection from Ministers… We do not ask for any special protection.”

In contrast to the views of many post-independence leaders who saw Adivasis as backward and in need of "upliftment," Jaipal Singh demanded that their autonomy be preserved, their cultures respected, and their ways of life protected.

This resonates with what the what I found doing my research as an anthropologist in the forests of Jharkhand: communities that are far more egalitarian than much of Indian society, where women enjoy greater autonomy and respect, and where democratic principles such as the fact that every household could be a leader in randomly selected, rotating leadership—are practiced in village assemblies. These resemble what we today call sortition and citizens assemblies, a practice now being revived in democratic experiments worldwide.

Jaipal Singh defended these cultural practices, even in contentious debates—like the one over liquor prohibition, which was to become a Directive Principle in the Constitution. Opposing the moralism of some Congress leaders, he argued: “As far as the Adivasis are concerned, no religious function can be performed without the use of rice beer.” In my own work, I have noted how Adivasi drinking customs are often misunderstood—by most Indians, including both the far right and the far left. Unlike in much of India, where alcohol is consumed privately and exclusively by men, among the Adivasis I lived with, rice beer and mahua wine are sacred, made at home, and shared openly by men and women alike—on market days, festivals, and sacred rituals. So I was delighted to learn that at one Adivasi Mahasabha meeting in 1940, held in response to a Bihar government liquor prohibition bill, the proceedings ended with a cheer: Hadia Peene Walon Ki Jai! —“Victory to those who drink hadia!”

Jaipal Singh often highlighted the egalitarian ethos of Adivasi gender relations and marriage customs. Unlike the rigidly hierarchical systems found elsewhere, Adivasi marriages were not solely arranged by parents—both the boy and the girl had their say. Sometimes, couples simply began living together without elaborate rituals. These unions were marked by bride-price rather than the crippling dowry system which has led to the disappearance of so many girl children elsewhere in India, and were modest in cost. Gender roles were grounded in mutual respect, reflecting a broader culture of dignity. So perhaps it is not surprising that in the Constituent Assembly debates Jaipal Singh was not only asking for more Adivasis to be brought into the deliberations but also more women. He complained, “There are too many men in the Constituent Assembly. We want more women…”

Jaipal Singh also admired the Adivasis’ deep reverence for nature and their simple yet profoundly meaningful lives. Their connection to the forest was not some naïve form of "nature worship," as often mischaracterised in stereotypes of indigenous people. Rather, it was a nuanced relationship—the jungle was something to be both revered and feared. Jaipal Singh wrote about the need for vigilance in the forest, home to elephants, tigers, leopards, snakes, bears, boars, and also deer, rabbits, birds, monkeys, peacocks, and more—always full of surprises. The Adivasis lived in harmony with this world, drawing sustenance from it—animals, fruits, roots, mushrooms, honey, white ants, firewood, twigs for toothbrushes, leaves for plates and headgear—while also protecting and preserving it

Despite Jaipal Singh’s early advocacy, the state of Jharkhand was only formed in 2000. By then, non-Adivasi outsiders had settled in large numbers, and Adivasis were no longer the majority. Moreover, contiguous Adivasi regions in neighbouring Chhattisgarh, West Bengal, and Odisha were left out of the new state. The exploitation of Adivasi communities has only intensified since.

In the 1990s, following India’s economic liberalisation, multinational mining corporations were granted access to mineral-rich Adivasi lands. The constitutional protections for land and forest rights—hard-won by leaders like Jaipal Singh and Verrier Elwin—came under renewed assault.

Using the pretext of combating an underground Maoist (Naxalite) insurgency—which had had taken root in some forested Adivasi regions—the state deployed hundreds of thousands of security personnel to occupy these areas. Under the banner of counterinsurgency, countless Adivasis were arrested, dispossessed, and in many cases, killed in extrajudicial encounters. Those who stood up for Adivasi rights were targeted. Among them was the Jesuit priest Father Stan Swamy, who had helped publish Jaipal Singh Munda’s biography in 2004. Devoting his life to justice for Adivasis, Stan Swamy was, like Singh, called a national traitor, falsely accused of terrorism and imprisoned without trial under draconian anti-terror laws. He died in custody in 2021 at the age of 83, during the Covid-19 pandemic. The causes Jaipal Singh championed—justice, dignity, autonomy—remain as urgent and relevant as ever.

What has often struck me is how, despite their mud huts and modest surroundings, many of the Adivasis I knew carried themselves with a quiet pride and dignity that felt almost aristocratic. Their rich cultural traditions, their sustainable relations with the environment, and their values offer deep lessons for all of us. Jaipal Singh embodied this blend of worlds—aristocratic in education and bearing, with an Oxford University pedigree, yet deeply rooted in the forest-dwelling simplicity of his people.

Decolonisation is a complex process. In India today, the British may be gone but the internal colonisation that Jaipal Singh was so concerned about remains. Back in 1946, in perfect Oxford English, he addressed the Constituent Assembly, saying, ‘‘we are millions and millions and we are the real owners of India. It has recently become the fashion to talk of ‘Quit India’. I do hope this is just a stage for the rehabilitation of, for the resettlement of, the real people of India. Let the British quit, then after that all the later comers, the later intruders quit. Then there will be left behind only the aboriginal people of India.” For him, it was not just freedom from white British rule over Indians that had to be fought for but also freedom from the grip of high caste outsiders that had impoverished Adivasis. He said, “if there is any group of Indian people that has been shabbily treated it is my people. They have been disgracefully treated, neglected for the last 6,000 years. The history of the Indus Valley civilization, a child of which I am, shows quite clearly that it is the newcomers – most of you here are intruders as far as I am concerned – it is the newcomers who have driven away my people from the Indus Valley to the jungle fastnesses.” Although he spoke of “intruders quitting” India, and although he held mistrust for many of the Congressmen in the Assembly, as Pooja Parmar highlights, he also appears to have held a genuine belief that Adivasis and non-Adivasis should work together for a more just future for the new India, and a more fair and equitable deal for Adivasis. Ironically, Oxford University and Jaipal Singh’s nurturing by British missionaries and elite society developed his talents and gave him the networks to fight for the justice of and against the internal colonisation of Adivasis, a struggle that remains important. And ironically, today the language of decolonisation in India has been hijacked as a weapon of the Hindu right to silence and imprison those like Jaipal Singh fighting for Adivasi and Dalit causes who are easily cast as anti-national.

Unlike leaders such as Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, or even Birsa Munda, who died three years before Jaipal Singh was born, and is widely commemorated as an Adivasi anticolonial hero, Jaipal Singh has received limited national recognition—aside from a handful of essays and the recent republication of his biographical accounts.

As Anand Teltumbde has warned of the idolisation of Ambedkar, it would be wrong to turn Jaipal Singh into a deity. No doubt it was not all glorious and Jaipal Singh had his limitations— for instance, we know that after the first general election of independent India in 1952, his own popularity and that of his party declined. It would be important to explore all the many contradictions of his life; the warts and the beauties of this aboriginal aristocrat groomed at Oxford University who fought for indigenous rights in India.

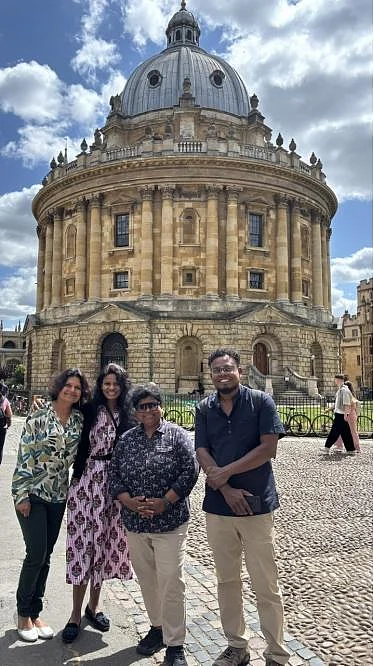

A new generation of Adivasi scholars is being born who can take this agenda forward in alliances with others fighting for the same causes. Last year I had the privilege of walking in the footsteps of Jaipal Singh Munda with Dr Regina Hansda, Lecturer in Development and Justice at the University of Edinburgh, Dr Richard Toppo, postdoctoral researcher at the University of Antwerp, and Ruby Hembrom, Founder of Adivaani publishing and doctoral candidate at the London School of Economics. We brainstormed what we can do to revive his legacy and wrote a letter to the Chief Minister of Jharkhand state, Hemant Soren, as a result.

The lack of recognition Jaipal Singh has received makes it all the more meaningful that the Jharkhand government, under CM Hemant Soren, in 2021 launched Master's scholarships to the UK and Ireland in the name of ‘Marang Gomke’. The CM’s visit to Oxford University tomorrow and in particular to St John’s College and its archives in the footsteps of Jaipal Singh Munda, marks an important moment. May institutions like Oxford University do more to revitalise Jaipal Singh’s extraordinary contributions. And may educational opportunities for Adivasi students in particular grow as a result and may they be aligned with the values Jaipal Singh held dear to focus on the spirit of the issues he cared about.

BIO

Alpa Shah is Professor of Social Anthropology and Fellow of All Souls College, University of Oxford. She lived as an anthropologist among the Mundas in Jharkhand and is the award winning author of ‘The Incarcerations: BK-16 and the Search for Democracy in India’, ‘Nightmarch: Among India’s Revolutionary Guerrillas’, ‘Ground Down by Growth: Tribe, Caste, Class and Inequality in 21st Century India’ and ‘In the Shadows of the State: Indigenous Politics, Environmentalism and Insurgency in Jharkhand, India’.