Summary of this article

Across healthcare, railways, and urban infrastructure, the state is withdrawing from direct service delivery not through sell-offs, but through long-term contracts and public–private partnerships that transfer control while retaining nominal ownership.

As pricing, staffing, and grievance redressal move into contractual frameworks, access to public services increasingly depends on the ability to pay, recasting rights-bearing citizens as consumers navigating tiered systems.

Once services are outsourced, democratic oversight weakens—RTI applicability becomes contested, penalties are rarely enforced, and reversals are locked out by long-term concession agreements

At 9.30 a.m., the corridor outside the radiology wing at a municipal hospital run by the New Delhi Municipal Corporation is already crowded. Patients clutch referral slips stamped with the hospital’s seal, but the counter they are directed to is not operated by hospital staff. A laminated rate card hangs above the glass window: MRI—Rs. 4,500. CT scan—Rs. 2,200. Payments are accepted via UPI. A notice taped to the wall explains that diagnostic services are being provided under a public–private partnership model, with complaints routed to a helpline number on the receipt.

“This is still a government hospital,” a senior doctor says, requesting anonymity, “but diagnostics are no longer part of the public system. We prescribe the tests, but we don’t control the service, the pricing, or the delays.”

Under a Request for Proposal issued by the New Delhi Municipal Corpotation, a private operator was selected to establish, operate, and maintain CT and MRI diagnostic facilities inside the hospital under a public–private partnership arrangement.

No announcement marked this transition. There was no legislative debate, no press conference declaring the privatisation of public healthcare. Yet a core function of a municipal hospital—diagnosis—has moved out of the state’s direct control through contracts that few patients, and even fewer doctors, have seen.

This is what privatisation of the public sector looks like in India today: incremental, technical, and quiet.

A Railway Station That Became a Mall

What has unfolded inside public hospitals is now visible, more conspicuously, in India’s railway stations.

Far away from the Delhi hospital, on a weekday morning at Rani Kamlapati Railway Station, the difference from older Indian railway stations is immediately apparent. The platforms are clean, the floors gleam, the food outlets resemble a mall food court, and security personnel gently but firmly discourage people from sitting on the floor.

Located in Bhopal, the station looks efficient, modern—almost aspirational. It is also something else: India’s first railway station redeveloped and operated by a private body under a long-term public–private partnership.

It offers what officials describe as an “airport-like experience”—automatic ticketing systems, a fully air-conditioned lobby, high-speed elevators, 24/7 power backup, purified drinking water, and a spacious covered parking area. The station has multiple retail outlets, food courts, a convention centre, office spaces, a hotel, and a hospital attached to it. The very idea of a railway station has been redefined.

While it is owned by Indian Railways, its day-to-day operations and maintenance are managed by a private developer. Previously known as Habibganj Station, it was redeveloped by a private body in collaboration with the Indian Railway Stations Development Corporation.

Gradual Privatisation of the Railways

Rani Kamlapati is not an exception. It is a model.

The Modi government has now begun transplanting this logic across other major stations. In policy documents and tender language, stations are increasingly described as “underutilised land parcels” with “airspace potential” and “commercial development opportunities”.

Major railway stations across the country are being considered for similar transformations under the same redevelopment model. Indian Railways’ station redevelopment programme borrows heavily from an approach that has already been normalised elsewhere: airport privatisation.

Under India’s airport PPP framework, the state retained control over air traffic, security, and regulation, while private operators took over terminals, retail, parking, and non-aeronautical revenue. Operators demonstrated that the real profits lay not in tickets, but in food, shopping, advertising, and controlled passenger movement.

That commercial logic is now being applied to public rail infrastructure.

From Public Infrastructure to Revenue Stream

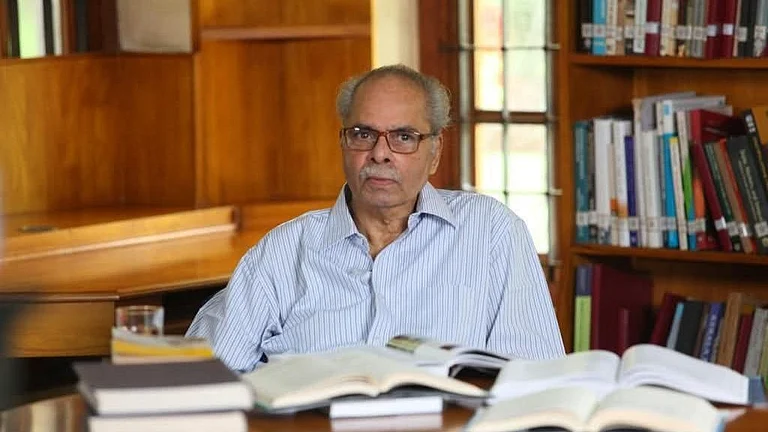

According to Sudip Dutta, president of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU), this is not an isolated experiment confined to the railways.

“It is a template,” he says, “that is being followed across the public sector.”

Dutta points to the National Monetisation Pipeline (NMP) 2.0—the government’s policy vision to monetise public sector assets by handing them over to private bodies for redevelopment, operation, and servicing, in exchange for a share of the revenue.

“The public sector is being privatised slowly and gradually at a level we can’t imagine,” he says, describing a paradigm shift in the model of privatisation the Indian state is pursuing.

“The NMP envisions the state as a landlord who constructs infrastructure and hands it over to private corporations for a couple of decades in return for a small portion of the revenue. The state is the new landlord.”

The union government, however, depends on asset monetisation to spur growth. Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has repeatedly said that public assets worth Rs. 10 lakh to be monetised for infrastructure growth. Besides, her has plans of capital expenditure through PPP mode and setting up of an Urban Challenge Fund of Rs. 10,000 crore redevelop cities.

She has defended bank privatisation, while underlining that nationalisation failed to meet goals. She said that professionalised banks achieve inclusion and growth better than nationalised ones even as trade unions counter that PSBs remain crucial for mass banking and rural credit

From Rights to Transactions

This shift is not merely administrative; it is ideological.

“A station used to be public infrastructure,” says a former Railway Board official. “Now it is a commercial node. Passenger service becomes one objective among many, not the primary one.”

Dutta argues that the state no longer sees people as rights-bearing citizens but as consumers—and the railways are only one part of a much larger transformation of government functions.

The same logic is visible in public healthcare.

For decades, government hospitals struggled with shortages of machines, technicians, and funds. PPP diagnostics were initially introduced as stop-gap solutions to bridge these capacity gaps. But contract design reveals a deeper shift.

Pricing authority, once a matter of public policy, is now embedded in agreements that allow for periodic revision by “mutual consent.” Termination clauses make early exit costly, requiring compensation for unamortised investment. Staffing is entirely contractual, outside public service protections.

“What changes is not just who provides the service,” says a public finance expert, “but how citizens relate to it. A diagnostic test stops being a public entitlement and becomes a priced transaction.”

Patients experience this most directly. The service still exists, and often functions more smoothly. But it costs more, and complaints no longer travel through political or administrative channels. They are processed as service tickets.

A Policy-by-Policy Retreat

From railways to health, public services are being reimagined across departments.

Government departments spend millions engaging third-party consultancies to write reports. Government hospitals charge for diagnostics run by private labs. Railways introduce differential pricing, premiumisation, and station “redevelopment” that displaces informal users. Education systems move towards contractual teachers, ed-tech tie-ups, and reduced state responsibility.

Privatisation has become the umbrella under which all of this is reorganised.

Policy documents are careful to avoid the language of privatisation. The National Monetisation Pipeline reassures that assets will not be sold—only leased. Ministries speak of “unlocking value” and “risk sharing”.

Yet long-term concession agreements with assured revenue streams function, in practice, like privatisation—without the political cost of saying so.

A senior audit department official puts it bluntly: “Parliament still answers questions, but ministers no longer control the service.”

Once services move outside departmental delivery, audit jurisdiction fragments. RTI applicability becomes contested. Grievance redressal shifts from democratic forums to managerial ones.

Quiet Privatisation

Unlike overt sell-offs, this form of privatisation operates through legal and linguistic subtlety. Ownership remains public. Trains remain government-run. Fares remain regulated. And yet, critical public infrastructure is removed from democratic control for decades.

There is no parliamentary debate on individual concessions. No public consultation on how stations or hospitals should function socially. The transformation arrives as a fait accompli—cleaner floors, shinier façades, higher rents.

Privatisation, in this form, does not announce itself. It normalises itself.

When railway stations are redesigned as profit centres, Dutta says, the poorest users are not banned—but they are made uncomfortable, unwelcome, and invisible.

“This is not headline-grabbing disinvestment or dramatic sell-offs,” he adds. “It is a low-noise, policy-by-policy retreat of the state from welfare, infrastructure, and public services—often framed as ‘efficiency’, ‘reforms’, or ‘public–private partnership’.”

An under-secretary in the Modi government told Outlook that the government avoids the political cost of outright privatisation by outsourcing core public functions—railway maintenance, diagnostics in government hospitals, school services—to private bodies; leasing instead of selling assets; and creating SPVs and concession models that transfer risk to the public and profit to private players.

“Ultimately,” she said, “a small set of corporate groups repeatedly win service contracts. Rising user fees and hidden costs ensure exclusion for poorer users. This also entails the erosion of accountability, as RTI no longer applies cleanly once services are outsourced.”

In an age where trade unions have been weakened, nationwide strikes no longer exert the same pressure. The middle class remains insulated, for now, through “premium” services. And the language of nationalism and efficiency deflects scrutiny.

This is not a defence of an idealised past. Public services were inefficient, understaffed, and often hostile to users under government-run service delivery system. PPPs did, in some cases, improve availability. But what is being lost is universality—the idea that access is a right, not a transaction; that accountability is political, not contractual; and that the state is responsible not only for outcomes, but for presence.

The question, then, is not whether public services should be efficient or modern, but who they are ultimately accountable to, asks Dutta. As governance moves from departments to contracts, and from rights to transactions, democratic oversight thins even as infrastructure gleams. The Indian state has not withdrawn from public life; it has retreated from responsibility without admitting it. And in that retreat, citizens are steadily recast not as participants in a shared public system, but as users navigating a marketplace built on assets that once belonged, unmistakably, to everyone.