“Welcome to Bhil Pradesh…” proudly proclaims 43-year-old Kantilal Roat, as he welcomes you to Dungarpur, one of the eight tribal-dominated districts in poll-bound Rajasthan.

As the desert state gears up for its 16th assembly elections, the Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), both seeded electoral contestants, appear to be trying their best to outwit each other on the mainstream political court. But away on the sidelines and below the eyeline, the steady rise of tribal identity politics in South Rajasthan, Dungarpur included, has thrown up several intrinsic challenges and questions, including a demand for a tribal state, ‘Bhil Pradesh’.

The ruling Congress, the BJP, the Bharat Adivasi Party (BAP) and the Gujarat-based Bharatiya Adivasi Party (BTP) have fielded their candidates for the 25 seats reserved for Scheduled Tribes representatives. And the BAP, a new political outfit that birthed a split in the older BTP seems to have thrown down the gauntlet to the BJP and the Congress in the state’s tribal belt.

The tribal-dominated electoral belt comprises Banswara, Dungarpur, Pratapgarh and five other districts: Udaipur, Rajsamand, Chittorgarh, Sirohi and Pali, which have significant tribal votes.

The intensity of BAP’s push has forced senior Congress and BJP leaders to frequently parachute to the tribal belt, armed with bags full of electoral promises.

Tribals account for 13.5 percent (2011 Census) of Rajasthan’s population. Among them, the Bhils are the oldest tribe, while the Meenas are the largest numerically. Among the other tribes are Damor, Dhanka, Garasia, Patelia, Seharia and so on.

Kunal Shahdeo, a researcher who works on adivasi politics, says, “With the upcoming elections poised for a tight contest between the Congress and the BJP, the tribal constituencies are set to play a pivotal role in determining the outcome of this crucial assembly.”

Shahdeo discusses the evolving voting patterns among tribals. Traditionally, influential tribal communities like the Meenas, he says, have staunchly supported the Congress. The question now is, whom will they lean towards this time?

“The BJP has gained traction among adivasi communities in recent years. It is evident in their electoral successes. The BJP strategically portrays adivasis as an integral part of the broader Hindutva umbrella, while some Congress leaders advocate recognising their distinct religious identity. The rise of BAP and BTP highlights the concerns of adivasis who have historically faced discrimination, exploitation and marginalisation despite electoral promises from both the BJP and Congress,” Shahdeo says.

Eye on Adivasis

With an eye on the Bhil vote and to stop its slide to regional Bhil political parties, former Congress President Rahul Gandhi during a rally on International Day of the World's Indigenous Peoples Day (August 9) invoked an anecdote involving the late Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, to drive home the critical significance of the etymology of the word 'adivasi', quoting his grandmother.

"When I asked my grandmother, Indira Gandhi, the meaning of 'adivasi', she told me it meant 'the first residents of India,'” said Gandhi, in his poll address at Mangarh Dham. He went on to speak at length about the term 'adivasi' and its relevance in defining the tribals' place in Indian society. Modern society, said Gandhi, needed to learn about its relationship with land, water and forests from tribals.

With regional parties like the BAP and BTP actively trying to corner the tribal vote at the state level, Congress directed leaders to organise 'Adivasi Gaurav Mahasabha' in historically significant tribal locations, emphasising the party's contribution to tribal equity and exposing BJP's failures in their welfare efforts.

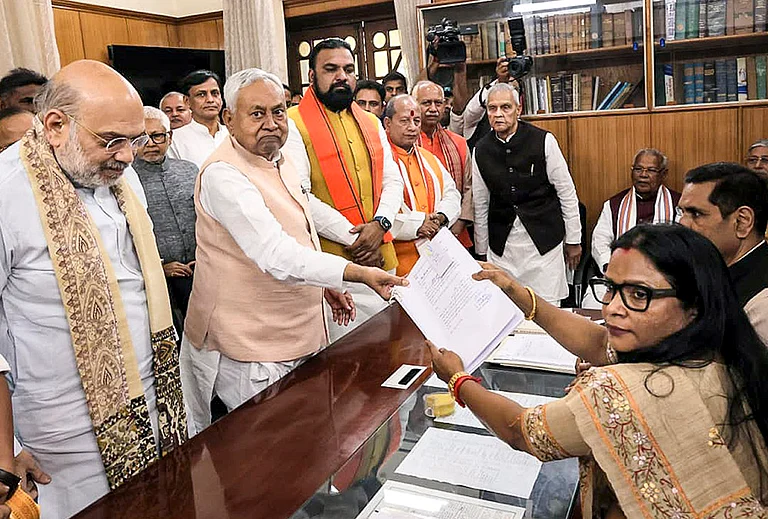

A month after Gandhi’s speech in August, the BJP appeared to double up its efforts to woo the tribal voter. Union Home Minister Amit Shah flagged off his party’s second phase of the ‘Sankalp Parivartan Yatra’ from Beneshwar Dham in Dungarpur. The site chosen for Shah’s rally holds significance in the political race for Rajasthan’s tribal vote. Beneshwar Dham is located at the confluence of the Som and Mahi Rivers and the annual fair hosted at the site hosts the largest tribal fair in the region.

Shah chose the site to sound the death-knell of Congress Chief Minister Ashok Gehlot’s reign. Shah, in his speech, also referred to the ongoing Sanatan Dharma debate, adding that only Prime Minister Narendra Modi could rule using Sanatan Dharma tenets. The Opposition bloc INDIA, he said, "hates Hinduism" and comments by its members were "an attack on our heritage".

On the one hand, while Gandhi slammed the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and BJP for calling adivasis ‘vanvasis’ (forest dwellers), BJP leaders countered the charge, insisting that the saffron party always supported adivasis, whereas the Congress misled people with “free schemes and crocodile tears”.

But with the emergence of regional parties rooted in tribal ethos, the real question is whether tribal voters will continue to believe in the promises of the two national outfits' leaders.

Shifting Power

In the 2018 elections, Dungarpur saw the BJP and the Congress each win one seat, with the BTP securing two. In Banswara, the BJP and the Congress each claimed two seats; an independent won one. Pratapgarh had the Congress and the BJP both bagging two seats. However, one noteworthy change was the victory of the Gujarat-based BTP party in two seats in that election and a close second place in several other seats.

Years of neglect and unfulfilled promises appear to have necessitated a political platform for tribals, ensuring their 'jal, jangal, jameen' (water, forests, land) rights. Kantilal Roat, BAP’s MLA candidate from Dungarpur, outlines the emergence of tribal parties advocating for mainstream recognition. He told Outlook that in 2018, the Gujarat-based BTP party, led by Chhotubhai Vasava, was invited to Rajasthan to support the Bhil community's political fight.

“However, there was one condition: the BTP would not control them remotely, nor would he (Vasava) impose a decision on us directly,” Roat says. Within a month’s campaigning, the BTP won two seats in Dungarpur —Rajkumar Roat from Chorasi and Ramprasad Dindor from Sagarwara. The Bhil leaders’ victory whetted a hunger for political representation from their own communities among the tribal population.

Post-BTP's 2018 victory, Bhil leaders in Rajasthan accused the party of making unilateral decisions without local consultation, notably during the 2021 Dhariyawad bypoll. Growing discontent led to an inevitable split in its ranks.

Following the internal party rift, local BTP leaders moved away from the parent outfit and formed BAP this year, which has now fielded 27 candidates across reserved ST seats, along with a few general seats for the upcoming elections. On October 9, the Election Commission allotted a hockey stick and ball symbol to BAP for the Rajasthan assembly polls. BTP has fielded candidates in 17 seats.

Politics of Religion

The fresh infusion and upsurge of tribal leadership is now emerging as a force to potentially baulk at the ‘religious politics’ of Hindutva organisations, mostly affiliated with the BJP and RSS.

“There has been a constant attempt to divide the state’s adivasis on religious lines: yena, kena, prakāreņa (in whatever manner possible). Currently, tribals in Rajasthan face two major challenges: religious politics and the dirty blame game of the two parties. The day these (things) stop, perhaps the leaders above would realise the true nature of the demands of adivasis. And trust me, it’s beyond what they think,” claims Roat, who insists that both the BJP and the Congress are alike. “The former practises religious politics openly, while the latter is subtle about it,” he says.

Rajkumar Roat, a BAP candidate from Chorasi speaks similarly.

“Compared to Indian urban spaces, tribal areas seem to lag behind by almost 100 years. We have not been able to shift our focus from the basic needs of khana, kapda, makan (food, clothing shelter). Our demands still remain the same—give us the rights promised under the Fifth Schedule,” he says.

“Unfortunately, the powers that be at the Centre never let our society know the importance and need of constitutional reservations—what are our rights and how much do we get?” questions Roat. Both the BTP and BAP have promised to fight to extend reservations in the private and the public sectors in their poll campaigns.

Along with the half-fulfilled demands based on the Fifth Schedule, the surge of tribal-oriented parties has also given rise to a clamour for a separate State ‘Bhil Pradesh’ based on the cluster of tribal-dominated pockets in Rajasthan as well as Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat

and Maharashtra.

Bhil Pradesh to Mangarh

The Mangarh massacre on November 17, 1913, has been central to formation of the tribal identity of the Bhil community in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat. The bloody massacre is often referred to as the ‘Adivasi Jallianwalla Bagh’ when around 1,500 tribals were killed by the British forces when they gathered in numbers to protest bonded labour and exploitation at the hands of the princely states and the British in Mangarh Hill. The area lies on the far end of southern Rajasthan split between Bansewara in Rajasthan and Santrampur in Gujarat.

Several leaders, including PM Modi, in his recent Mann Ki Baat address in October this year, made a reference to the Mangarh massacre. However, such statements across party lines appear to be made with an eye on the tribal vote-bank, ahead of the polls.

In November last year, PM Modi addressed a rally at the Mangarh Dham and paid tribute to Guru Govindgiri, known as Govind Guru, who led the uprising against the rule of the princely states and the British.

“Unfortunately, in the history written post-Independence, the Mangarh massacre was not given its due place. Now, the country is correcting the mistake committed decades ago,” thePM said, declaring the Dham as a national monument.

In 2017, former Rajasthan Chief Minister Vasundhara Raje initiated the National Tribal Freedom Struggle Museum, costing Rs 12.37 crore. Despite the foundation, the museum remains incomplete since the Congress assumed power the following year.

Locals in Dungarpur argue that these high-visibility moves are often strategic during elections, focusing less on recognising tribal identity in its truest sense. Velaram Ghogra, BTP state president says, “Both the Congress and BJP’s love for tribalism is seasonal, only limited to elections”. BAP leaders allege that if mainstream political leaders valued the tribals’ struggle and really wanted to honour the Mangarh massacre, they would have supported demands for a separate Bhil state.

Among the tribal population, the Bhils have the largest hold on all the ST seats. Hence, the demand for a separate Bhil state assumes significance and has been a major electoral demand.

“Bhil Pradesh is our right and the fight for this separate state is a tribute to the struggles of our forefathers. It has been a difficult struggle for the Bhils of Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. In our case, it is the rightful owners of these lands who are demanding a state of their own, where they can live and cultivate with their own resources,” says Kantilal Roat.

Further, feuds over adivasi lands have increasingly become a socio-political issue at the state and central levels. In Dungarpur, tribal leaders allege that if the Samata judgement of 1997 must be fully implemented to protect these lands, then mineral resources can be generated and farming can be done with the proper inflow of water.

“Over time, tribals from the Scheduled areas have experienced significant land-loss to larger corporations. And the same has been done, overlooking the financial obligations owed to tribals. Protecting and allocating lands to us would reduce the migration of our people, thereby addressing the rising issues of migration and economic distress,” says Rajkumar Roat.

Water Woes

Water scarcity persists in Rajasthan's tribal belt, compounding land-loss issues. Jeevan Devi Roat, ex-sarpanch of Padli Gujreshwar gram panchayat, Dungarpur, highlights that during the Mahi dam's construction (1972-1983) in Banswara, a significant tribal section lost lands without compensation.

“The purpose of this dam was to provide water. It does provide water, but to Gujarat. People living right beside the dam still do not receive regular, safe drinking water,” says Devi.

Tribal leaders of south Rajasthan believe that the “dirty politics” of the Congress and the BJP should rise beyond religious politics and bogus empathy towards the tribals. “If they really cared or care for us, allow us water, land rights, implementations under the Fifth Schedule and our own Bhil Pradesh,” they echo.

(This appeared in the print as 'Yena, Kena, Prakāreņa')