Summary of this article

Amid shrinking spaces and growing intolerance towards political cartoons, on the 11th death anniversary of R.K. Laxman, Outlook asks political cartoonists: Is cartooning a dying art?

Papers, like the Mid-Day, that continue to champion cartoonists, are becoming rare.

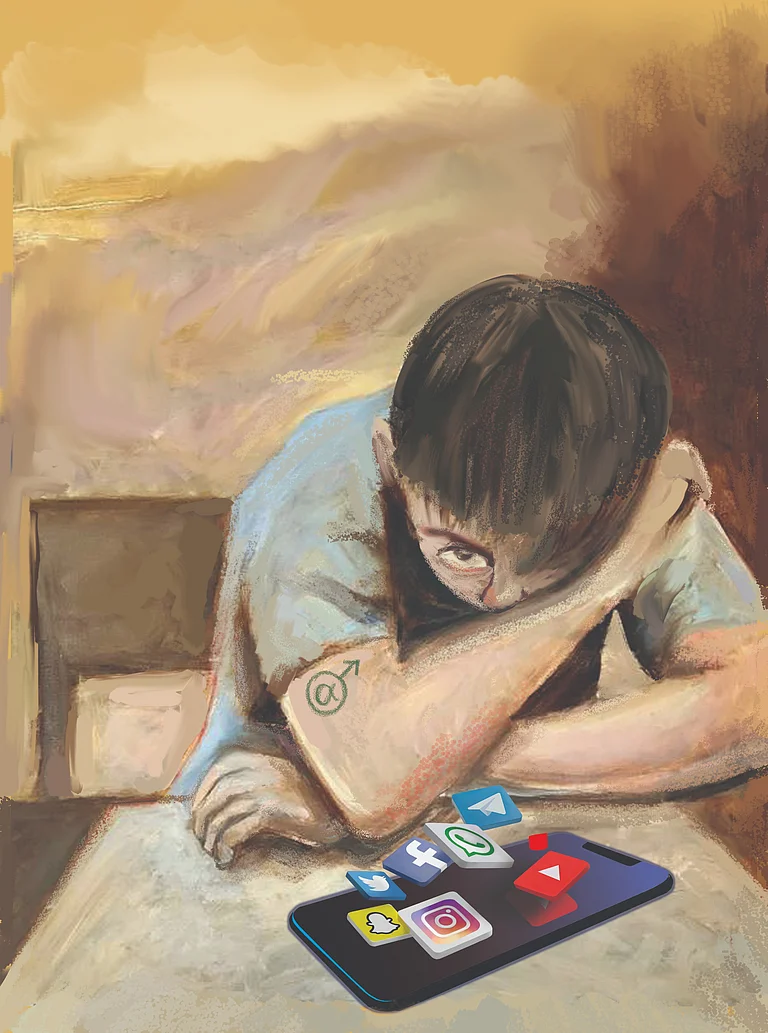

The power of social media over the last decade has given a platform to many critical voices that would have otherwise been missed.

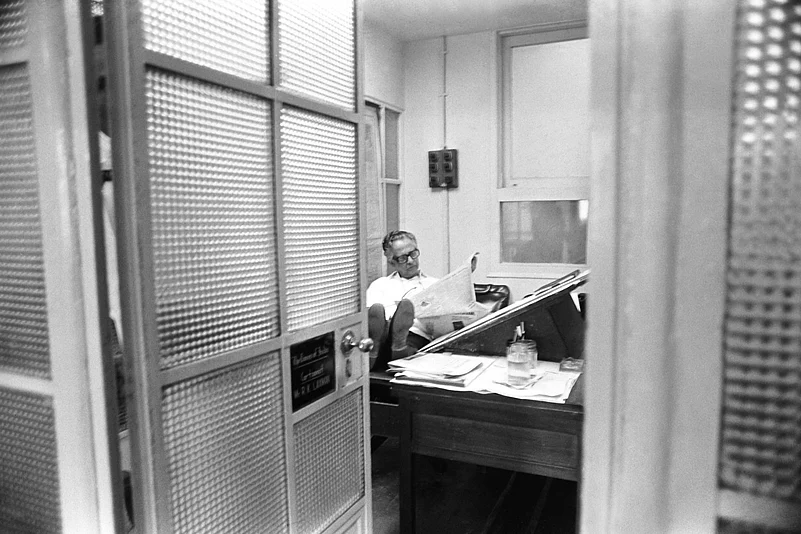

There was once a time when India woke up to its morning tea and a chuckle over the newspaper cartoon. This was the era when R.K. Laxman’s work featured daily on the front page of The Times of India. Eleven years after his passing, spaces for comics and political cartoons in newspapers are rapidly shrinking, as intolerance and legal cases against cartoonists rise. It appears the actual common man may have lost sense of humour.

Now, political cartoonists face the threat of being slapped with legal cases, being booked under the Information Technology Act, subjected to online abuse and threats, shadow-banned on social media, and, in some cases, exposed to real risks to their personal safety.

Just as all good cartoons come with irony, so does the field of cartooning, as the biggest challenge cartoonists face comes from newsrooms themselves.

Self-censorship and editorial interference run deep in print newsrooms. The survival of honest, unfiltered cartoons—once embodied by the irreverence of the Common Man—now depends largely on the courage of the editor. Multiple rounds of editorial revisions and the quiet dropping of cartoons have become routine in print newsrooms.

“What used to be indispensable – the stand-along political cartoon – may have become an extinct species. Pocket cartoons don’t have the same impact. The political cartoonist is disappearing, ” said Outlook’s founder editor-in-chief Vinod Mehta in a 2013 article for The Hindu.

Outlook spoke to political cartoonists to gain an insider's perspective of what goes on when the laughter stops, and trouble begins.

When asked to bend, they crawled

In 2018, eminent political cartoonist Satish Acharya faced a major editorial clash with his then-employer, a Delhi-based afternoon newspaper. This clash resulted in the withdrawal of his column from the paper. The editor rejected Acharya’s cartoon portraying India being surrounded by China’s growing influence. This cartoon, titled ‘Claws’, was just one of the several works the editor had sent back or rejected as per Acharya.

“The episode in which my cartoon was rejected by the editor was just the beginning of an era of editorial intolerance,” Acharya tells Outlook.

In a public response to the clash, Acharya wrote, “Cartoonists are not bound to mimic the editor’s voice. Cartoonists are supposed to, and expected to express, independent voices.”

Reflecting on the self-censorship he encountered, Acharya invoked L.K. Advani’s Emergency-era remark: “When asked to bend, they crawled.”

Eight years on, Acharya says little has changed. “I have lost many more clients who succumbed to the government’s pressure. Even the editors who are relatively brave now ask me to tone down the criticism of the government or not to show ‘certain’ people in my cartoons.” He argues that editorial timidity inevitably shapes the cartoonist’s work. “One of the biggest changes I observed is that editors have forgotten their professional duty of questioning the government. Many of them have become part of government PR, pushing the government’s narratives as news.”

Independent journalist and graphic cartoonist Rasheed Kappan describes the media today as increasingly “cagey.”

“The media itself is now cagey about going beyond a particular point in criticising anybody. The business of media is already under threat, and that reflects in the works of those employed by them.” While cartoons have disappeared from several papers, even those that retain them have reduced their allocated space.

Of veteran cartoonist N. Ponnappa’s work in a leading daily's Bengaluru edition, Kappan notes that the space is “so small you need a lens to read what he has written.”

Papers, like the Mid-Day, that continue to champion cartoonists, are rare. Creator of the comic strip Zal that has been running weekly in the Mid-Day since 2018, Cyrus Daruwala says, “I've been given complete freedom to create what I want to without editorial interference.”

As traditional media has allegedly shifted from being watchdog to lapdog, political cartoons appear to have paid the price for flying too close to power. While Laxman’s Common Man remained a silent observer with a classic bewildered expression for 50 years, today it is cartoonists themselves who inhabit that irony—watching their independent voices quietly erased from the page.

As print retreats from the cartoonist’s pen, another platform is beginning to redraw the boundaries altogether.

A new era: Social media

The power of social media over the last decade has given a platform to many critical voices that would have otherwise been missed.

One of these voices belongs to Rachita Taneja, the creator of the viral Sanitary Panels comic strip. Known for its stark stick figures and unapologetically political satire, the strip began on Facebook in 2014 as a private experiment meant to amuse friends. Today, Sanitary Panels commands over 133,000 followers on Instagram and is regularly featured by The News Minute for its fearless commentary.

“I believe Sanitary Panels would not have been possible without the Internet,” says Taneja.

She adds, “As space for dissent shrinks, and mainstream media falls in line with those in power, social media is a way for political artists to post their work without facing the same level of censorship. This is evident to decision makers as well, which is why we are seeing efforts to exercise greater control over social media platforms.”

A similar trajectory defines the work of Sharanya Eshwar, a fact-checking journalist and political cartoonist known online as hiccuped.

Eshwar claims, “When working for a news organisation, there will be censorship.” The cartoonist used to write for a news organisation and accompany her article with a cartoon. However, the column was discontinued by the organisation. She says, “It was discontinued due to the current political landscape and the fear of threats.”

Compared to working for a newsroom, Eshwar enjoys the freedom and independent voice she has on social media, where she can post her uncensored works.

Acharya too mirrors the freedom to post unrestricted cartoons on social media. “So far, I’ve been adamant, and I made sure that the rejected cartoons reached the audience through social media. As a cartoonist, it’s my duty to do justice to this wonderful art form.”

“Social media has been a blessing for a cartoonist like me, who has been abandoned by many publications. Social media helped me build my own cartoon-loving community, who accept & respect my right to criticise every politician,” he says.

As visibility increases, so does scrutiny—bringing with it surveillance, harassment, and consequences that extend far beyond the screen.

A double-edged sword

Over the past few years, cartoonists have observed a shift in social media algorithms alongside a broader crackdown under the current regime—both working against the visibility of political comics. Taneja claims, “In the past decade or so, we have seen strategic targeting of voices that have been critical of the ruling party. If one dissents online, they are bombarded with vile and hateful harassment. This is by design to create a climate of fear of speaking out.” While she has faced sustained backlash and trolling, she notes that for every hateful comment there are many more messages of support, sustained by the community Sanitary Panels has built online.

In 2020, Sanitary Panels made national headlines after the Supreme Court consented to a law student initiating contempt proceeding against Taneja over cartoons related to the bail hearing of TV journalist Arnab Goswami. The case accused her of portraying the apex court as biased towards the ruling government in two tweets.

Taneja declined to comment on the matter, as proceedings remain ongoing, but reaffirmed the core of her work: “my work questioning those in power remains unchanged.”

In early 2025, Satish Acharya received notices from the Mumbai police via the platform X, objecting to posts featuring his cartoons. Responding publicly, Acharya wrote, “So happy to know that Mumbai is so peaceful with perfect law & order situation that the police are now focusing on cartoons.” He argues that the IT law is increasingly being misused to target journalists and critics, with law enforcement weaponising its provisions to intimidate cartoonists.

Digital suppression has emerged as a shared experience. Rasheed Kappan has faced shadow-banning, while Eshwar has received threats from alleged right-wing social media accounts.

Despite harassment, legal pressure, and algorithmic erasure, the cartoonists say they continue to draw—placing ethics above safety, and dissent above silence.

The Offence Is Intentional

R.K. Laxman believed that “a cartoonist enjoys not a great man but a ridiculous man.” It was a freedom he fiercely defended. In a meeting with Indira Gandhi, Laxman pointed out that the Emergency laws curbing press freedom had begun to affect his work. When the Prime Minister found his cartoons insulting, Laxman replied plainly: “Cartooning is the art of insult and ridicule.”

That very freedom Laxman relished is today increasingly read as dissent. Cartoons that were once humorous yet critical are now viewed as seditious.

“The political atmosphere has changed, but cartoonists haven’t changed,” notes Satish Acharya. What has shifted, he argues, is power’s relationship with the press. “Politicians have learnt the art of ‘managing’ the media, thanks to some greedy journalists and editors. I’m sure Laxman would have struggled to deal with the social media scrutiny, or he would have completely stayed away from the social media circus.”

For artist Taneja, the problem lies in institutional courage. “I don’t think the editors would have the courage to show the same fervour as the Common Man. It would likely be seen as a liability, the same way a lot of senior editorial cartoonists are being seen as one now.”

Political cartooning may no longer occupy the front page, and it may no longer enjoy the protection of the newsroom, but it continues to exist. The satire must survive not because it is funny, but because it is necessary.

As India marks Republic Day and salutes the Constitution, it is worth remembering that the freedoms it promises do not stop at polite agreement. They extend to those who ridicule power, question authority, and risk offence—one panel at a time.

Perhaps the more unsettling question, then, is not whether cartooning is dying, but whether it would be allowed to live today at all. As Acharya put it, “My curiosity would be about the support Laxman enjoyed from the publication he worked for. You think Laxman would’ve got the same level of support now? I doubt.”

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&format=webp&w=768&dpr=1.0)