“It is dangerous to dabble with the past to secure the present political future.” Historian S Irfan Habib deployed this ominous truism to raise concerns over the government’s attempts at—what many opponents of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) have often referred to as—saffronisation of history in textbooks for school students.

By deleting entire chapters, editing out and omitting key portions of social science and history lessons, the National Council of Educational Training and Research (NCERT) has once again drawn attention to the political interference in education and curriculum in the country.

That’s nothing new—successive governments have altered syllabus as per their political convenience and often added hagiographical elements while omitting events and ideas inconvenient to them. However, there is an undeniable link to the deletions made by the NCERT in its latest curriculum changes.

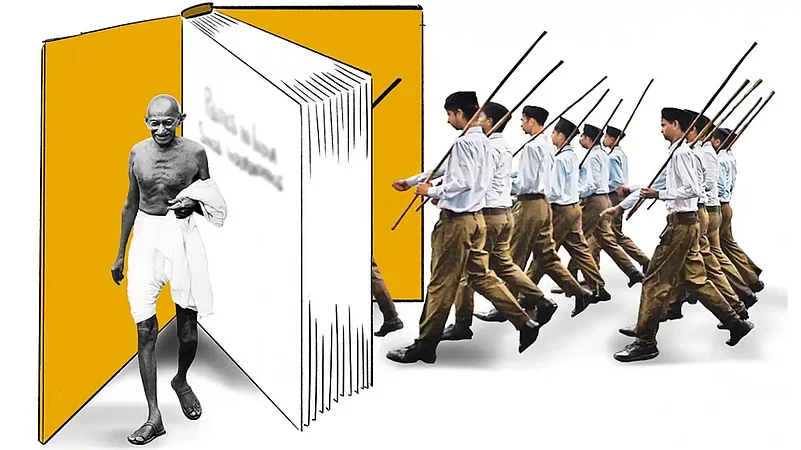

These are some of the omissions carried out by the NCERT in the school textbooks in the latest controversy. Paragraphs on attempts by Hindu extremists to assassinate Gandhi and the ban imposed on Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) after his killing have been dropped. All references to the 2002 Gujarat riots have been dropped from all NCERT social science textbooks. Content from the Mughal era and previous Muslim rulers of India have suffered cuts. Three chapters detailing protests that turned into social movements in contemporary India have been dropped from political science textbooks across Classes 6 to 12. The section on varnas in the Class 6 history textbook is reduced.

The excerpts and themes deleted do not appear to be random. They need to be seen in totality. These events, decades and centuries apart, are connected through one common thread—they sit uncomfortably with the RSS vision of Hindu nationalism and re-telling of history envisaged by the organisation and its political wing, the BJP.

For instance, Gandhi’s legacy as a secular Hindu leader murdered by an extremist Hindu Godse has always been an eyesore for the political Hindu right in the country. So has been the legacy of the Mughal period, which has been under assault through changes in the names of cities or communalisation of their history through a Hindu-Muslim binary.

Political scientist Gilles Verniers says the rewriting of key passages of the NCERT textbooks was aimed at removing from school curriculum historical facts that are inconvenient to Hindu nationalists. “The irony is that in order to critique history, one needs to know it first. What is happening here is not a scholarly debate over the interpretation of historical facts related to key aspects of India’s recent and more distant history, but the manufacture of ignorance about those facts,” says Verniers.

Through minor and major changes to the text, the NCERT has created a situation which could make students drastically re-imagine an event, person or political phenomenon. In a world where truth and facts are highly contested through alternate realities and narratives, half-truths, incomplete truths and distortions alter the way historical events are understood. This has a bearing on our present and future. The lessons of the past risk being never learnt.

The NCERT has justified the edits and omissions in the name of “syllabus rationalisation” and termed these portions to be “overlapping” and “irrelevant.” However, questions have been raised about its uprightness.

Some of the omissions made were not even publicised by the NCERT on its website till a recent report in The Indian Express revealed that the updated textbooks that hit the markets had dropped content, especially pertaining to Gandhi and the ban on the RSS, which was not mentioned in the list of rationalised material released by the NCERT. Dinesh Saklani, the NCERT director, brushed it aside by attributing it to a possible “oversight.”

This is not the first time that the NCERT, the apex body entrusted with publishing school text in the country, has courted controversy for deleting or altering the curriculum. Political interference with education is an accepted fact in India. The first few months of the Janata Party government were marked by a major controversy around attempts to communalise textbooks, points out Verniers. The first and second tenure of the NDA government was also marked by major controversies about modifications made to textbooks.

In 2018, Disha Nawani, a professor at Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), mentioned that not just the centre but several state governments like Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Haryana have at different points in time proactively interfered with text-books prescribed in their state schools. “Such revisions have unabashedly followed their particularistic agendas and flouted due procedures set for the same,” she wrote.

Opposition parties and prominent scholars have accused the NCERT of distorting history and revisiting it with a communal prejudice, and of homogenisation. The Communist Party of India (Marxist) politburo said that the “current efforts to revise the textbooks are actually intended to whitewash the divisive and violent role of the RSS is evident in the manner in which the crucial sentences regarding the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi which led to the ban of the organisation is sought to be struck off.”

Binoy Viswam, a CPI Rajya Sabha MP, in a letter to education minister Dharmendra Pradhan, said the removing text on the ban on the RSS in the wake of the assassination of Gandhi was “an attempt to conceal the role” of the outfit “in the heinous act from the future generations.”

The ruling BJP has vociferously defended the omissions. One of its ministers accused the previous Congress regimes of being the actual manipulator of India’s “historical facts.” The “Barbarism of Mughals, the era of Emergency, the genocide of Kashmiri Pandits and Sikhs” never made it to text books, said BJP MP Shobha Karandlaje. “BJP is only correcting your wrong doings,” she said in a post.

The BJP says the Congress did similar things and that it especially overemphasised the Mughal history and promoted text by ‘leftist’ scholars. But is there any parallel between the syllabus changed during the BJP rule and the successive Congress governments?

“Textbooks produced under previous regimes have been at times criticised for being too hagiographic, or not critical enough about India’s founding political figures. The period of Emergency also was also not adequately treated in school textbooks. But that was not to the point of erasing history or voluntarily distorting historical facts,” said Verniers.

Tanvir Aeijaz, a professor at University Of Delhi (DU), concurs with this standpoint. He says the latest changes are highly political and ideological in nature. It is “extending the polarisation process and mobilisation at the academic and curriculum level,” he says. “It’s important to discuss what had been rewritten rather than who did it,” warns Aeijaz on the ongoing debate.

The opposition leaders and scholars offer themselves solace by arguing that the regime can change the text in books but cannot ignore the actual history. There is also a lot of corroborative material, historiography and archaeological findings that make them believe that the truth will survive no matter how deep the efforts to stifle it.

Access to the Internet has also changed how we debunk lies and distortions. It is true that changing facts will not wipe out the incident but they do re-shape the way students perceive it. In the post-truth world, messaging is important. So is every-day memory of the past.

Aeijaz considers the latest deletions a disservice to the nation. “Students are not allowed to make their own choices properly. Since students reading these materials are at an impressionable age, it stays with them. Students are seen as guinea pigs,” he says. The same could be said of truth and history.

There is much more at stake than the accuracy of what is being taught to children in the textbooks, says Verniers. “Textbooks contribute to shape ideas about who is and what is to be an Indian. They are meant to teach key concepts that are at the foundation of India’s constitutional order. As such, they should not reflect the partisan and selective choices that parties make about history,” he says. But the fact is all political parties are guilty of trying to change the past according to their ideologies.