Trigger Warning: This article contains mentions of suicide and mental health conditions. Reader discretion is advised. If you or someone you know is struggling, please contact these numbers. | Helpline: iCall (9152987821) or AASRA (+91-22-27546669) — Available 24/7.

World Mental Health Day on October 10 raises awareness, but what about improvement in health care services for those living with mental health illnesses?

Nearly 2,00,000 Indians die by suicide every year, according to World Health Organisation's (WHO) figures.

Meanwhile, India's expenditure on mental health is one per cent of the health budget, which itself is measly two per cent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

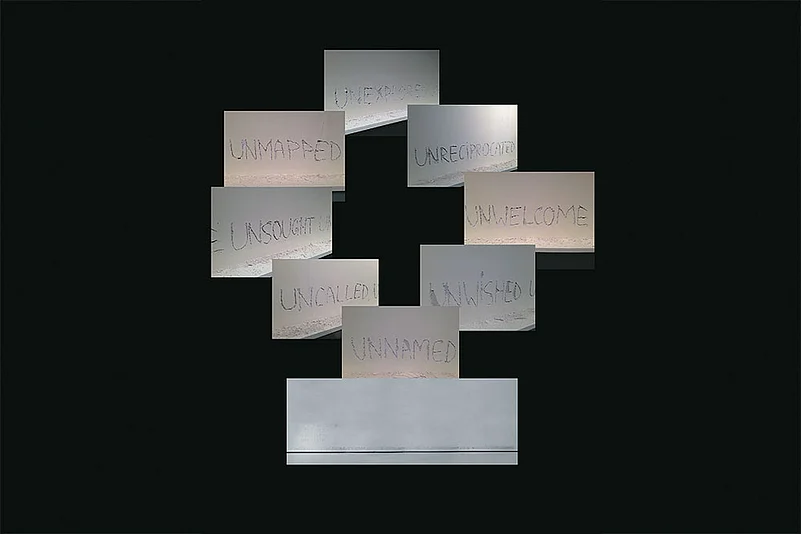

“In This City, I am Memory” —Elie Wiesel

Another rainy day, the third in a row. Water falling in sheets and the road looks not very different from the canal flowing next to it. I am glad I am not driving. Rumi is. He is an animal-loving youngster, waiting for his green card or whatever document is required for living in Canada. Most young people in Punjab villages are waiting for it. Many of the old people have already been there and do not want to go back. “There is nobody to talk to” is why, if you ask them.

The hospital is forty minutes away and this is the time when I read my emails. There are three unread. Two are identical, wanting me to click on a link and become rich in ten seconds. The third is a request to come to such and such university and give a talk to students on the World Mental Health Day, on October 10. I will probably say no, and that would be a first.

By the end of the said Mental Health Day, there would have been many seminars, talk shows, discussions and debates. It would also have been pointed out that nearly 2,00,000 Indians die by suicide every year, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) figures, and that each suicide inherently is an avoidable death. And that for every completed suicide, there are ten attempted suicides.

That the country’s suicide data is compiled by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) is itself a telling indictment of our country’s attitude towards the massive tragedy called suicide. What will not happen on ‘the’ Day, is a rupee increase in budget for wholesome mental health services. There would surely be a lot of ‘stay positive’ floating around, which to me is throwing the onus back on the sufferers and amounts to victim shaming. Who thinks negative by choice, anyway?

And the rest of us will continue to be content with the fact that country’s expenditure on mental health is one per cent of the health budget, which itself is measly two per cent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). But this is not just about money. This is about priorities and our allocation is proportionately lower than that of Ethiopia, Sudan, Ghana, Afghanistan, Bhutan, Botswana and Congo, all of which are poorer than India, but probably wiser.

This is in spite of the fact that an article in Lancet Psychiatry reported that it actually makes sound financial sense for countries to treat mental illness early, as it being so common—one dollar invested in its treatment yields a return of four dollars by way of increased productivity. It means that for countries, it is much cheaper to treat mental illness than not to.

It is ironic that in a welfare state one has to use the ‘bang for buck’ argument to remind the GDP obsessed planners that treating the mentally ill early will lead to an increase of 0.5 per cent in the GDP in the short run, and more in the longer run. It is also not generally known to the planners that relatively small amount of funding for mental health goes a long way in establishing basic mental health services since treatment of mental illness involves almost no technology or equipment and in 95 per cent of cases are outpatient-based.

Health in India is not a political subject. No election, not even at the municipal level, is fought on the issue of health and if a senior politician is offered health portfolio, he would probably get offended.

When I was training to be a psychiatrist, decades ago at PGI Chandigarh, I was told that India had just 300 psychiatrists and once that number reached 3,000, all its mental health problems would be solved.

Today, India has about 10,000 psychiatrists and it still seems far from enough. From this, you might conclude that patients are crowding the waiting rooms of mental health clinics and psychiatrists struggling to see all those patients. Nothing is farther from truth. The fact is that a large number of patients cannot access mental health services and most private psychiatrists, who outnumber those in the public sector, do not get enough clients to fill their time.

My own waiting room on this rainy morning is empty except for a mother and her school-going son. The son looks indifferent to the surroundings with his gaze glued to the TV screen. The mother, dressed in jeans, with head covered, is a gynecologist, the absent father, a surgeon. Crying into the phone, she had told me the previous night that the son had pushed her head against a wall, causing a nasty cut, which the husband had to stitch up. From the bandage on the forehead, when she removed the chunni, it seemed to be a large wound. The provocation? She had tried to snatch his phone after he refused to switch it off for the third time in four days, even an hour after the “agreed to” time. His previous school had expelled him for using phone in class and the present one was threatening to. Locking up the phone resulted in dramatic bouts of him banging his head against the wall till the parents, late for their clinic, caved in. I explained to the mother about behavioral addictions and in view of the violence, the need for admission. She had seen rows of young men with heroin addiction in the other waiting room and her face had fallen, but just for a moment.

The parents had already read up about the short cuts to thrill, whether drugs or the Internet being addictive, and about the desperate need to escalate to get the same thrill. And the intense craving if you did not. And even if we had different waiting rooms for the two, the caste system was artificial.

The next was an old couple, both over 75, living in the old age home, which had come up last year not far from the hospital. Old age homes, an oddity in Punjab till recently, are now a part of normal conversations. Retired government teachers, both had depression, both were forgetful and both had a sense of humor, which cheered me up after the youngster, who had been passed on to the psychologist.

“Our main problem is that every evening we forget when it is 8 AM in Canada and miss our call time with our son and grandchildren there. It is getting worse,” the wife informed. “I tell her it is good that we forget. How long can you go on living from one telephone call to the next? Maybe forgetfulness is a blessing,” the husband adds, with a glint in his eyes, which quickly changes to sadness.

The mid-morning was the stable follow-ups, familiar faces, who had dropped in to get their medication titrated and, as Joy put it, “just to say hello”. Joy, a couple of years back, during a bout of excitement, had stopped traffic on the highway. Today, he looked as normal as any of us treating him. The running grouse he has is with his family. “I had lost my mind but you were normal. Why did nobody get me treated till the whole city knew?” he keeps asking.

An old class-fellow from medical school days, now a GP in a nearby town, dropped in for coffee, wanting to know what could he do for his fifteen-year-old grand-daughter, who had not gone to school for two months and was forever on Instagram, when she is not looking into a mirror, finding fault with her nose or forehead or lips. She had refused to come with him since “the defects actually exist”. I advised for an online counselling session with a psychologist, to start with. “I think these sites are run by some plastic surgery conglomerate,” the grandfather said bitterly before leaving.

Rumi drove me to a town an hour and a half away from the city for lunch and a seminar on the subject, ‘Whither Community Psychiatry?’ About time, I think. Sometime ago, following the global hue and cry, we too had joined the bandwagon and emptied out our mental hospitals instead of humanising them. To the families and patients, we promised a cushion of community care nearer to home, something that never existed, nor did by then bigger houses or joint families.

“How does one look after one’s father with dementia or one’s brother with schizophrenia in a two-room flat on the third floor, with an unfriendly housing society, when the insurance does not cover long-term hospital care?” someone asked pointedly.

On the way back, the evening sky was overcast, as we passed through a village. Old people were sitting outside their houses, and I was reminded of my stint in Goa long ago and old couples sitting outside baroque houses, with their children, in Portugal.

Rumi answered, although I had not asked anything—“It is eight in the morning in Canada, the calling time.” And I hoped the forgetful old couple I had seen in the morning had remembered to calculate correctly.

“But why is everybody outside?’’

Anirudh Kala is clinical director at Mindplus, Ludhiana