Every Eid, Mohd Mosam returns from Bihar—where he works in construction—to his home in Palda village in Muzaffarnagar, Uttar Pradesh, and memories of his childhood come flooding back.

Mosam hasn’t always lived in Palda. He was born in the nearby Kutba-Kutbi village, about four km away. Somewhere in the middle of the road between Palda and Kutba-Kutbi lies a little brick dome that the locals believe was built by Babur. Inside is a maze “just like the Bhul Bhulaiya in Lucknow, though smaller”. Mosam remembers how he and his friends—mostly Jats and Jatavs—played inside the gumbad (dome) on Eid, and later ate sevayyian (sweet vermicelli pudding) at his home in the evening.

It has been eleven years since Mosam lost his childhood home to communal violence, dubbed the ‘Muzaffarnagar riots’ of 2013. He says that it wasn’t just the home that was lost. “We lost our childhood”.

As Muzaffarnagar prepared to go to the polls in the first phase of the Lok Sabha elections on April 19, memories of violence and displacement hung heavy upon Muslim voters, who comprise a substantial portion of the electorate in UP and yet have seemingly become socio-politically invisible as citizens in the past decade.

Muzaffarnagar and After

The 2013 Muzaffarnagar violence remains a turning point in the political and social fabric of UP, especially in western UP. The clashes between Jats and Muslims began with the killing of the Muslim youth Shahnawaz by Jat boys Sachin and Gaurav. The two were, in turn, lynched by Muslim villagers in Kawal village, which sparked a spiral of violence that altered the existing social and electoral bonds between the two dominant groups. The divide played a decisive role in the Bhartiya Janata Party’s 2014 Lok Sabha sweep in UP by breaking up the ruling Samajwadi Party’s (SP) Muslim-Yadav vote bank.

After the riots, which left over 60 dead—officially—the BJP managed to win all seats in western UP following a highly polarised and communally-driven election campaign in 2014 led by leaders like Sanjeev Balyan, sitting MP from Muzaffarnagar, who is also a minister in PM Narendra Modi’s cabinet. Incidentally, Balyan, a former veterinarian, is from Kutba-Kutbi, where Mosam’s family had lived.

The charred remains of Mosam’s home, a locked-up mosque and a madrasa remain silent reminders of the violence that unfolded in Kutba-Kutbi, days after the incident in Kawal, located nearly 80 km away. On the ill-fated day, Mosam had been inside his newly-renovated home, spread over a 1.5-bigha plot, with his pregnant wife and extended family when they heard that Jat mobs were entering the village with guns and swords.

“When the mobs reached our village and started firing, we ran to our neighbour’s house. They are Harijans. We hid in their bathroom and watched the rioters set fire to our house and loot it,” he recalls. They could only escape once the CRPF forces arrived in a few hours. Eight people of Kutba-Kutbi were killed by the mob and about 2,500 Muslim residents displaced.

The 2013 Muzaffarnagar violence remains a turning point in the political and social fabric of Western UP.

“We had to rebuild our lives from scratch in Palda. The Hindu community here was kind and accepted us. But there is looming mistrust on both sides,” says Mosam, known locally as ‘Mosam Lohar’. The Hindu residents of the village inform in hushed voices that since 2013, the village has not seen a Hindu Pradhan. “A majority of the people who left the riot-struck villages never returned, altering the demographics of the regions in which they settled,” says Rajeev Pratap Saini, a veteran journalist and local Hindu community leader from Palda.

Elaborating on the shifting Muslim-Jat relations in western UP, Comrade Daud, a Students’ Federation of India member of the Saharanpur chapter, says that in previous decades, Muslims and Jats had a “roti ka rishta”—they could eat one meal each at the other’s house. “An important socialist aspect of this Jat-Muslim bond was their ability to protest against industrial exploitation of sugarcane farmers. These groups together owned and worked in the sugarcane farms spread across this region and jointly agitated against farmers’ exploitation by industrialists or capitalist governments,” he says.

Hindu-Muslim unity has been at the foundation of the agrarian farmers’ movements in western Uttar Pradesh, led on the one hand by Jat leaders like Mahendra Singh Tikait and on the other hand by Muslim farmer leaders like Ghulam Mohammad ‘Jaula’, who once gave the call for “Allah Hoo Akbar Har Har Mahadev”. He passed away in 2022.

The duo was involved in the proliferation of the Bhartiya Kisan Union (BKU) among both Hindus and Muslims of rural west UP following the group’s reorganisation in 1986. Jaula, who got his moniker from his native namesake village in Budhana, one of the six assembly constituencies of Muzaffarnagar Lok Sabha seat, was intrinsic in forging key socio-political bonds between Jat and Muslim farmers.

After 2013, Jaula and other Muslim farmer leaders grew alienated from the larger farmers’ movement after Tikait’s sons allegedly lent support to the BJP following the Muzaffarnagar riots. Though attempts were made by Jaula to once again revive the Jat-Muslim solidarity during the recent farmers’ protests, his death left a gap in the secular Muslim leadership that is yet to be filled in the region. Today, Jaula’s village is home to hundreds of Muslim families who were displaced from nearby Shamli and other regions in 2013. As per conservative estimates, 20,000-25,000 families were displaced across UP. A majority of them have not returned to their home villages.

While the Akhilesh Yadav government at the time issued compensation of Rs five lakh to victims for rehabilitation, a 2017 report by Amnesty International along with AFKAR India Foundation found that at least 200 families are yet to receive any compensation. Many residents of “Ekta Colony”, the name locals gave to the cluster of displaced households resettled in Jaula after 2013, remember CPI(M) leader Suhasini Ali who had personally come down to meet them and had given Rs 50 lakh (1 lakh per family) to the victims settled here for rehabilitation. Party cadres were also active on the ground in 2013, helping with relief distribution across the temporary refugee camps that had sprung up at the time.

Identity Vs Religion

The Hindu-Muslim narratives have waned in volume as compared to the 2014 and 2019 poll campaigns, but religion and caste remain the principal electoral pegs in UP. While addressing a rally at Meerut—which goes to polls on April 26—where the BJP has fielded actor Arun Govil of TV’s Ramayan fame, PM Modi alleged that the Congress’ manifesto has an imprint of the “Muslim League”. At a campaign rally held by Balyan in Yahyapur village in Muzaffarnagar district ahead of the April 19 elections, ‘folk’ singer Chanchal Banjara, credited for songs like “Bulldozer Baba”, japed about “Pakistan waley” living in fear of the BJP and praised the government for passing laws like the CAA and the abolition of Article 370 in Kashmir. The songs were a hit at the rally, attended largely by the Rawa Rajput community who call themselves “vegetarian Rajputs” (as opposed to the disgruntled Thakurs currently raising hell against the BJP across west UP).

Chaman Singh, a 90-year-old farmer from Yahyapur, which has a minority Muslim population, says that before 2017, people in the village were afraid to go out on the streets for fear of being mugged, raped or killed. “The BJP has silenced the SP’s Jat and Muslim miscreants,” he adss.

The Muslim vote (19 per cent of total voters in UP) is nevertheless key in a number of seats where polls were held on April 19, including Muzaffarnagar, Saharanpur, Kairana, Rampur, and Nagina. Analysts feel that Muslims can act as “plus voters” in many seats like Saharanpur or Nagina. Inversely, a split in their votes is likely to help the BJP. In Saharanpur, where Muslims form over 40 per cent of voters, followed by Scheduled Caste voters at about 20 per cent, the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP)—which currently holds the seat— has fielded Majid Ali, a popular OBC leader, with an eye on Gaud and Telli Muslim votes. The Congress (INDIA bloc) has fielded Imran Masood from the politically-prominent Masood family.

While campaigning in Behat district amid Ramzan, Masood expressed confidence that the Congress and the INDIA bloc had the full support of Muslims. “The BJP has always tried to divide but the Congress has always stood for inclusion,” he said. He also alleged that the BSP is working as the BJP’s “silent partner”. Nevertheless, Masood, who is infamous for his ‘boti boti’ comment against PM Modi, has recently been making overtures toward Hindus, visiting temples and speaking of Ram, leaving many voters like Ikram Ali amused. The 71-year-old resident of the Deobandh district, where BSP’s Majid Ali was campaigning, expressed doubts about both candidates. “Ali is popular among OBC Muslims, he works hard but the BSP might be playing to both sides. Masood is also a strong leader and may get support because of his family legacy, but he has not won this seat the last two times, which makes us doubt if he can do it this time,” Ali says. The fact that Masood is a party hopper (he was in Congress before joining the SP, then the BSP after which he returned to the Congress) is also mentioned with a pinch of salt.

Meanwhile, the BJP’s Raghav Lakhanpal, who became MP in the polarised election of 2014 after the Muzaffarnagar violence, winning the seat for the BJP after 16 years with a margin of 60,000 votes, is confident that the BJP will manage to get “400 paar” (over 400 Lok Sabha seats) this time. He says that his party does not fight based on religion. “We stand for sabka sath sabka vikas. Our focus is on development and fighting corruption,” he says. A similar stance is expressed by Balyan, who is likely to face a tough fight from SP’s Harendra Malik, a well-known Jat leader from Khatauli. The BSP has fielded Dara Singh Prajapati. Out of the total 18 lakh voters in Muzaffarnagar, five lakh are Muslim, 2.5 lakh Dalits, 5.5 lakh OBCs (including Saini, Pal, Kashyap, Prajapati), 1.5 lakh Jats, 1 lakh Vaish, 1 lakh Thakurs and 1 lakh Brahmins-Tyagis). If Muslims follow their traditional pattern of supporting the SP, analysts like Saini predict a neck-and-neck fight. “This year, the BJP is facing anger from the Thakurs over ticket distribution. There is anger among sections of Tyagis and Sainis as well. These are the BJP’s core voters. In case they shift, the Muslim ‘plus vote’ might make or break the fortunes of a candidate in at least four seats,” the Muzaffarnagar native says.

In Kairana, Iqra Hassan, fighting on an SP ticket, is being predicted as the favourite, with a massive Muslim support base in her favour. In Nagina too, the majority of Muslim voters are likely to decide the fate of the BJP, the BSP and ‘Ravan’-led Azad Samaj Party. Both Kairana and Nagina were scheduled to vote on April 19. The community, however, feels that under the clamour for Muslim votes, the real issues of a majority of the Muslim population in the region remain unheard.

In previous decades, Muslims and Jats had a “roti ka rishta” in Western UP. This has changed now.

What Do Voters Want?

The election buzz was palpable in Saharanpur ahead of the April 19 elections.

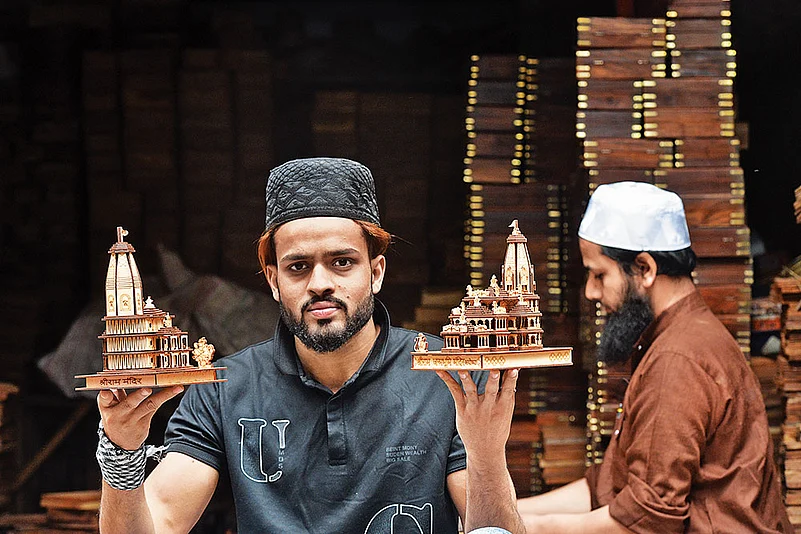

Wood carver Mohd Muzammil is known for his immaculate Ram Mandir replicas. Sleek and polished, his replicas were quite in demand in January when the temple was consecrated in Ayodhya. The sales of the replicas have now dwindled. Muzammil and other artisans and woodworkers in the Khata Kheri market of Saharanpur nevertheless keep some in stock, on display. The Khata Kheri market, known these days as “the Wooden City”, is a staid example of the communal congruity that was once characteristic of these parts.

“We have been making temples for decades and a majority of our customers are Hindu,” Haji Muntazir, who owns a shop on the same street, says. He and his family have been in the woodwork business for over five decades and have always lived in Saharanpur. “The Hindu-Muslim problem has been created by the media to help political parties during elections. But come here and see, everyone lives in harmony,” Muntazir says.

Mohd Ahfazzul, another wood shop owner, says that the price of sheesham has gone up from Rs 600-700 per square foot to Rs 1,200-1,500 in the past five years. “The GST implementation has also hurt our business. These are the issues that matter to us,” he says. Mohd Mubassir, a B.Sc. student and nursery owner from Buddha Kheda village in Saharanpur, highlights the importance of promoting higher education among Muslim youth. “Most of the children in poorer Muslim families study in madrasas which have been targeted by the government. Private schooling is expensive and as the youth grow old, many, including my peers, lose interest in studies and turn toward some kind of small business”. He urges the government to formulate special schemes for the education of marginalised Muslim children. He further points out that rampant exam paper leaks are a grave matter for students of UP, irrespective of religion, that the government should look into.

Voters also complain of increased religious discrimination. In Muzaffarnagar City, Abdul Mannan, the Imam of Meenakshi Chowk mosque, says that Eid celebrations have become muted in recent years as Muslims are not allowed to blare sirens that indicate the time of starting and breaking roza. There have been arguments about the volume of azaan in the past and city authorities have prevailed. “When Kaawar Yatra happens, devotees can blare DJ music till late in the night. We feel local authorities discriminate against our religious festivals,” he says. Last Karwa Chauth, Muslim mehendi artists were beaten up by local goons allegedly linked to Hindu Mahasabha for putting henna on Hindu women’s palms.

In the refugee settlement of Jaula, residents lack schools and hospitals. Daily wager Mohd Raashid, 50, complains that the only government school in the area (till class 8) keeps changing courses and teachers remain absent, affecting his sons’ education. Salma Bibi, another displaced resident from Lat Bawdi and a mother of four young sons, claims that there are no doctors in the village, no ASHA or Anganwadi workers visit the colony and residents have to bear long hours of electricity cuts. There was no electricity in the neighbourhood amid Eid weekend festivities. She claims that since the BJP came to power, not a single neta has come to meet them or lend their support. “Even the road in this village was built by a former Pradhan, Haji Jamshed, with his own money. The government did not build anything here for the refugees”.

Many like businessman Haji Muntazir posit that the ‘Muslims only vote for Muslims’ myth was first peddled by the Congress. “We vote for whoever works for the improvement of our people and our country. But the BJP completely ignores us as voters.”

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Rakhi Bose in Muzaffarnagar and Saharanpur

This appeared in the print as 'Remains Of A Riot'