Recent Chinese Investment In India

- TBEA in power sector

- Fosun in Pharma and API

- Wanfeng Auto Wheels, Kingfa and Lesso in Auto components

- Trina Solar, Jinko Solar, Golden Concord Holdings in Solar modules

- Huawei and ZTE in telecom

- Sany and Liugong in construction equipment

- Gionee, Huawei and Xiaomi in consumer electronics

***

Despite the unresolved border issue, disputes over territory and, most recently, lingering tension over the impasse at Doklam, China continues to be one of India’s largest trading and business partners. In the last few years, trade between India and China have leapfrogged—official data puts it as worth about $75 billion.

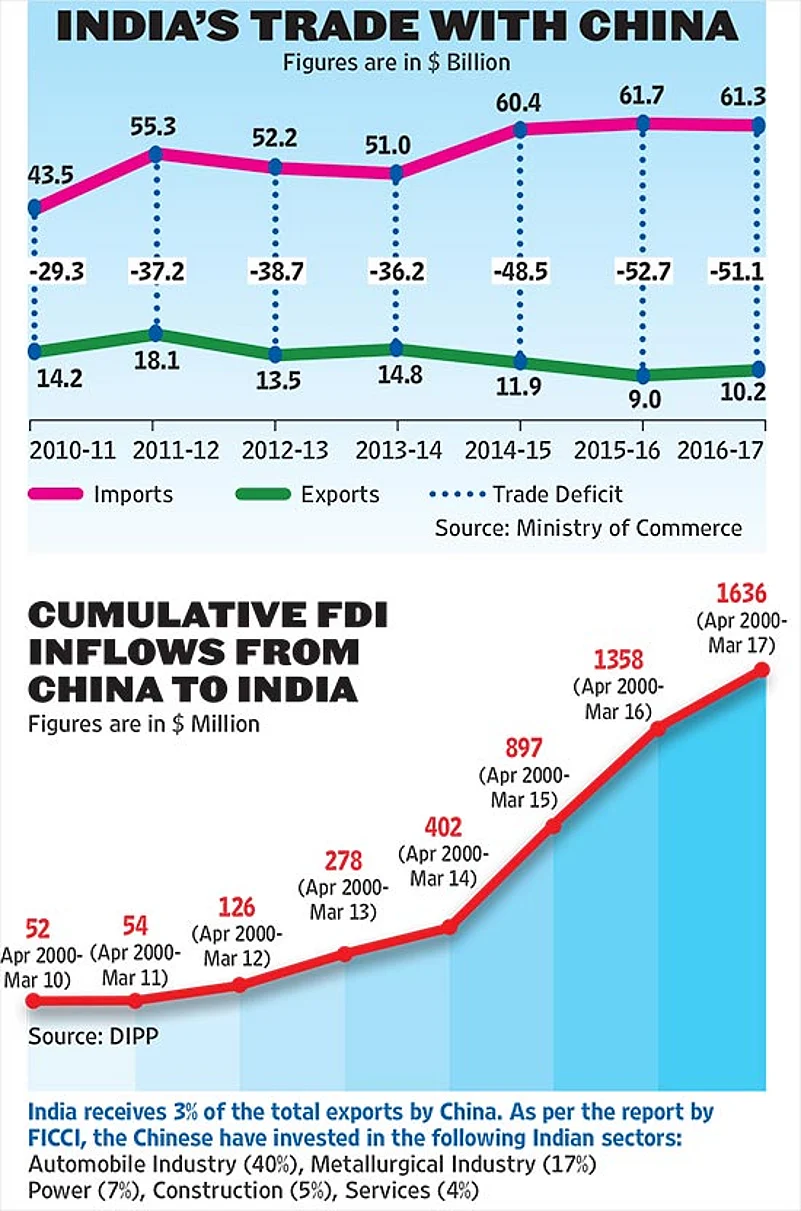

Yet, concernedly, India has a huge trade deficit with China, which means our imports from China far exceeds our exports to it. According to data from the Union Ministry of Commerce, India imported goods worth $61.3 billion from China in 2016-17. During the same year, India’s exports to China were worth just $10.2 billion—a trade deficit of $51.1 billion in China’s favour. Among China’s top trade partners, its trade surplus with India is second after the US. But more importantly, that deficit has been increasing and now accounts for nearly half (47 per cent) of India’s total trade deficit.

The ongoing border crisis has raised fears of a confrontation between India and China and, consequently, the fate of business and trade ties. If a conflict does break out, China will have a big market to lose; given its humongous trade surplus, the Indian market matters hugely to it. A lot of Chinese ancillary and small-scale industries also fully rely on the Indian market.

At the same time, India will be affected too, because it sources a lot of cheap equipment from China, particularly in the telecom network and power sectors. However, compared to the US and European economies, which are far more exposed to China, India is in a safer position. Says Ajit Ranade, chief economist, Aditya Birla Group, “If China stops exports to India, we will have to get it from somewhere else and we may not get the same price advantage, as Chinese prices are much lower than anywhere else, though their prices are firming up and quality improving.” What India may lose is access to a potentially big Chinese consumer market worth $2 trillion—much bigger than India’s GDP.

However, Ranade feels that strong trade and investment relations between countries help in diffusing political disputes. The high level of business ties with India lessens chances of a confrontation, as both countries have a lot at stake and the impact of a conflict on their respective economies could be huge. Even China-US relations aren’t at their best—indeed, China’s trade surplus vis-a-vis the US, its largest trading partner, is a bone of contention—but their strong business ties whittle down the prospects of a conflict. Besides, China’s GDP and its currency have both taken a hit in the last two years, which may force it to privilege economic compulsions over political and nationalistic pressures.

India’s imports from China in 2016-17 consisted of electronics items worth $21,982 million, iron and steel worth $1347 million, machinery and parts worth $11,124 million, optical and medical goods worth $1,321 million, organic chemicals worth $5,616 million, fertilisers worth $1,251 million, plastics worth $1,849 million, iron and steel articles worth $1,234 million, ships and boats worth $1,454 million and vehicles and parts worth $1,112 million.

Against this, India’s exports to China paint a sorry picture, including ores, slag and ash worth $1,623 million; sulphur, earth and stones worth $557 million, cotton worth $1,348 million, electrical items worth $396 million, organic chemicals worth $887 million, iron and steel worth $367 million, mineral fuels worth $789 million, plastics worth $296 million, copper and articles worth $708 million.

India has been seeking more access to Chinese markets in some areas, including pharmaceuticals and services. However, the pharma industry faces several challenges in China. These include time consuming and expensive approval processes, complex post-registration steps, including pricing, provincial tendering and hospital listing and marketing and distribution, given China’s large and diverse geography. The IT and IT services sector—India’s major foreign revenue earner—too is facing regulatory and business issues. On top of that, a towering language barrier creates problems for all Indian firms in China.

Most significantly, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) from China into India has been historically low as compared to other countries. Experts feel that the trade deficit India has with China could be offset by increased FDI from China. Says Rajat Kathuria, director and chief executive, Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER), “FDI from China has been notoriously low as compared to countries like France, South Korea and Japan. This is surprising, because China is a huge exporter of capital, but India is not their destination. China is investing heavily in power equipment, boilers, telecom network and optical fibre cable, but India gets just a fraction of it.”

According to a paper by CII, potential areas of Chinese FDI into India include power transmission and distribution equipment, railways, telecom equipment, industrial parks and townships, apparels and medical devices, where there is a huge potential for Chinese firms to invest in India.

However, there are encouraging signs—in the past two years, there has been a surge in FDI inflows into India from China, primarily in the e-commerce sector, through Alibaba and Tencent and in the telecom sector in companies like Xiaomi, Gionee, Huawei, Vivo and Oppo. Also, last month, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), a China-led international financial institution which finances infrastructure projects, approved a loan of $329 million to build access roads to around 4,000 villages in Gujarat.

According to data from the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP), cumulative FDI inflow from China increased from $1.35 billion in the April 2000-March 2016 period to $1.63 billion in the April 2000-March 2017 period. Says Ranade, “In the last two years, FDI inflow from China has been more than the cumulative value of the last 12 years.”

Chinese companies have also been active players in the Indian road construction sector and many top Chinese power companies like China Datang Corporation and China Southern Power Grid are keen to enter India’s power sector, while some are already here. But their most significant presence is in the telecom infrastructure sector. In a few years, Chinese companies like Huawei and ZTE have pushed out older favourites like Nokia and Ericsson in the telecom network business and today have a significant market share. Newer networks like Reliance Jio, too, have cut down costs by bringing in Chinese vendors for their networks.

Ranade says there are four potential areas in which India and China can do business. The first is pharmaceuticals, where India is seeking markets in China, which is looking at lowering healthcare costs. The second area is IT and IT services—though India is present in that sector in China, the exposure is much less than in other countries.

A third, greatly promising area is tourism, where India can gain a lot from China. At present, just 50-60,000 Chinese tourists visit India, while there are 107 million outbound Chinese tourists worldwide. Even if India garners 10 per cent of that, it would be a multiple of the current numbers. India can also promote its areas of Buddhist pilgrimage, creating a major draw for Chinese tourists and make upto $2 billion in revenue.

Then there is the entertainment sector. Recently, Dangal became one of the largest grossers of all times in China; before that, 3 Idiots was a big box-office draw. If India can profitably export Bollywood to China, it can bring in a lot of revenue.

Experts feel that even intractable political issues cannot dismantle the level of business ties between the neighbours. And the upward curve of Chinese FDI inflow into India has strengthened those ties. What India needs now is to seriously look at the ever-burgeoning trade deficit with China and increase its efforts to lock in on Chinese markets to bring in some correction. The more it inches towards an even keel, the less can it be disturbed by political manoeuvering.