Boong is a Manipuri film directed by Lakshmipriya Devi.

It follows the story of a little boy in Manipur, who wants to bring a gift for his mother.

From within an everyday domesticity, the film introduces the intense backdrop of Manipur's history.

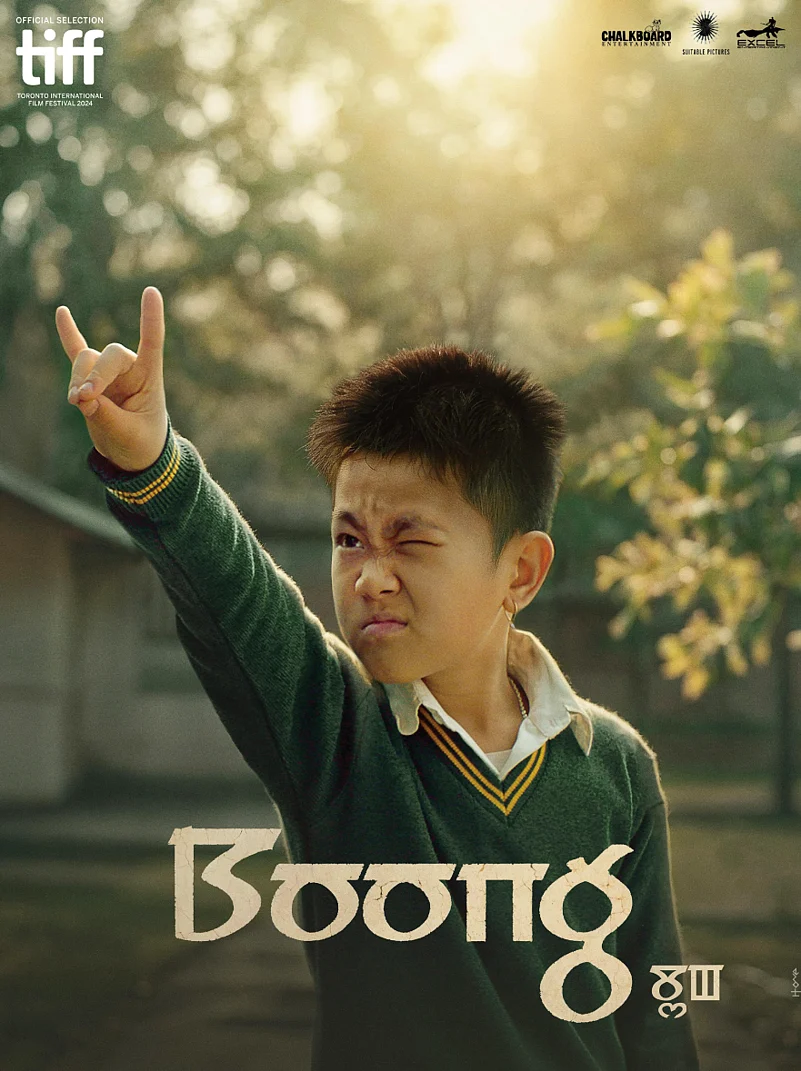

A small boy, in his attempt to bring back a gift for his mother from his father, moves through the complex history of Manipur in the most unassuming way. Boong (2024) by Lakshmipriya Devi allows the audience to see and understand the state’s military and political situation, without overburdening the plot with explicit narratives on insurgency. The film primarily revolves around two characters: Brojendro (Gugun Kipgen) a.k.a. Boong (literally meaning “little boy”) and his mother, Mandakini (Bala Hijam Ningthoujam), who awaits her husband’s return from Moreh town. Mandakini runs a small business in the women’s market in Imphal, while Boong attends a local school. It is from within this domestic, everyday cycle that the film introduces a more intense backdrop: Manipur’s history of revolutionary movements, political unrest, and the deeply rooted dichotomy between insiders and outsiders.

At first glimpse, Boong may appear to be an intensely political film. However, while politics forms an integral and affective layer, it remains subtle and emerges in nuanced ways. The film’s ability to present such serious issues through a young boy’s journey, while still sustaining the political urgency, is what makes it stand out.

Boong’s father has been away in Moreh for years and has not returned. Aware of his mother’s desire, Boong decides that he will personally travel to Moreh—a town on the India-Myanmar border in Tengnoupal district—and bring his father back as a Holi gift to her. What follows is a boy’s journey that steadily uncovers the consequences of Manipur’s military and political ambience. The audience is first drawn into the insider-outsider (or mayang) debate, which threads throughout the narrative. This unfolds through the contrast between Boong’s friend Raju (Angom Sanamatum), who has a brown skin tone, and Juliana (Nemetia Ngangbam), a fair-skinned child. Despite their close bond, Raju and his father are constantly subjected to bullying because they are outsiders. At school and during his search for Boong’s father, Raju is attacked by children calling him “blackie.” Moreover, Boong and his mother are criticised for engaging with outsiders (Raju and his father), whom some view as an embarrassment to the community. Even Boong himself, in moments of anger, repeats, “Outsider, go back! Go to Rajasthan.”

Such moments are not always projected with heaviness, but are woven with comic relief. For instance, when Raju hears Lungi Dance being played in Moreh, he exclaims, “This is an outsider’s paradise,” referencing the fact that Hindi songs are not allowed in Manipur. He also introduces himself with exaggeration, mentioning his name, city, state, pin code, and country to military personnel. These scenes highlight how larger political situations infiltrate mundane, everyday lives, particularly those of children. It reveals how the state’s conflicts have long-term, generational consequences.

Manipur has, for decades, been a site where cultural restrictions were imposed by militant groups seeking to “preserve” Meitei/Manipuri culture. Hindi films were banned in the late 1990s, and it was only recently that student groups attempted to screen them. Within this context, the insider–outsider divide, along with the categorisation of Hindi cinema as a foreign influence, becomes a central motif. The irony lies in the persistence of English as a superior marker of privilege. This is evident when Boong, eager to join an English-medium school, intentionally misbehaves to be expelled from his current school. Juliana, meanwhile, mocks Boong and Raju for their lack of fluency in English. Here, language itself becomes a marker of division—of history, class, and privilege.

The opposition deepens with references to banned Hindi films and cultural artifacts. Boong treasures a Madonna poster belonging to his father, the last object connecting both of them. At the same time, the village chief maintains a secret screening room, adorned with posters of Mary Kom (2014), where films like PK (2014) are played. When Mandakini discovers this, she threatens to expose the screenings, knowing it would endanger the chief, who had forged her husband’s death certificate. Yet, on her way back, she nostalgically recalls the time her husband took her to the chief’s house to watch Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998)—the last Hindi movie screened in Manipur before the ban was imposed. The inclusion of such memories reflects an intention to convey Manipur’s history within the film’s domestic and personal narratives.

The state’s political tensions remain in the background, never an overbearing presence; however, they constantly shape the story. Whether through speculation about Boong’s father’s involvement in revolutionary movements, the forging of documents, the insider–outsider hostility, or the ban on Hindi films, the political remains understated but inevitable. When Boong eventually reaches Moreh, helped by Juliana, the plot takes an unexpected turn: it becomes less about insurgency and more about betrayal and infidelity. The revelation that his father may not be a martyr, as the audience may have presumed, but a man who abandoned his family, destabilises the earlier political readings. Yet, the ambiguity remains crucial. The film rarely establishes the work that Joykumar (Boong’s father) was actually pursuing in Moreh. This open-endedness sustains the narrative’s curiosity and allows an interpretive engagement. Boong also encounters JJ, a trans woman whose intervention helps him discover the truth. Through JJ, the film incorporates queer presence into the socio-political fabric, subtly but significantly.

The film manages to sustain audience engagement by interlacing these multiple components: socio-political history, questions of identity and belonging, queer narratives, and the innocent yet determined pursuit of a little boy. While the story is deeply personal, it is always entangled with the larger political setting. This is a captivating way to present Manipur’s history—at once serious and carefree. The seriousness lies in the subject matter; the naive determination of two boys chasing a goal larger than themselves makes it carefree. The balance between the two is what gives Boong its effective power.