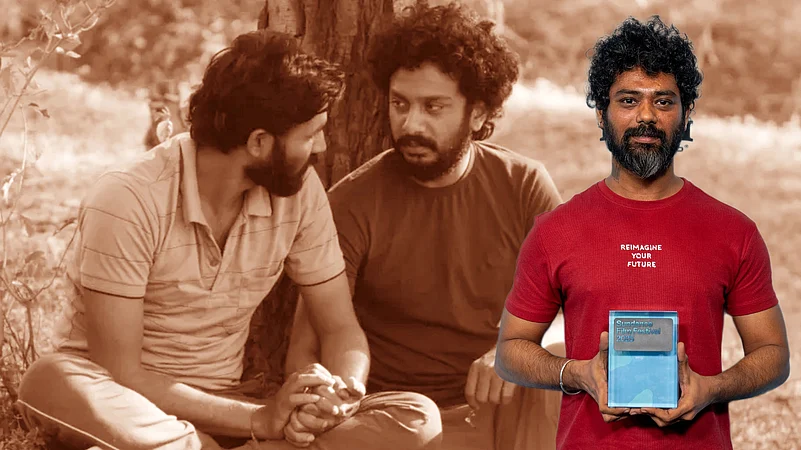

Rohan Kanawade's Sundance winner Sabar Bonda (Cactus Pears) is all set for its long-awaited Indian release

In this interview, the director takes us through the long incubation journey of the film

Kanawade emphasizes why he didn't approach this as a queer film

At this year’s Sundance Film Festival, Rohan Kanawade’s quietly radical Sabar Bonda (Cactus Pears) quickly made many firsts, from being the first Marathi feature to premiere to nabbing the Grand Jury Prize in World Cinema Dramatic Competition. It is the kind of film that blooms deep, entwining grief and closure within a soft, swelling romance. Even while drenched in sorrow, light steals in, shimmering off its indelible trio of actors–a soul-baring Bhushaan Manoj, both Suraaj Suman and Jayshri Jagtap gently blazing themselves on our heart. As a bereaved Anand arrives in his ancestral village for his father’s funeral rites, thus rolls at him a spate of claustrophobic social expectation to marry. Amidst the battering weight, hope and possibility unfurl in a rekindled relationship between Anand and Balya, a farmer. In the shadow of death, life glows into being.

Ahead of the film’s long-awaited India release on 19 September, Rohan Kanawade sat down with Outlook’s Debanjan Dhar to discuss the script’s evolution, writing with images, working with natural elements, his reservations with Sabar Bonda being slotted a queer film. Edited excerpts from the conversation:

You say you don’t have a particular roadmap while writing—no outline or character history. How much of intuition vs planning is involved in developing a narrative? Do you need to know what the ending might look like or you figure along the way?

Most of the time, I figure things along the way. Before I started writing, I knew I didn’t want a tragic ending for this film, but that it must end on a hopeful note. I had no idea, though, what the climax would look like or how things would proceed to that point. All I had in my head were visual notes for few sequences, some sound notes because many things came from the real-life mourning period. But a large part of the film—the romance—was fiction. I knew few details about the characters, but the incorporation of them in the screenplay was gradual. David Lynch says the filmmaker’s currency isn’t in the outline or the character arcs but the finished screenplay. That’s the spirit I believe in.

Sabar Bonda has been through several development labs. Were you very sure in your vision even while starting out on these rounds? Carlos Reygadas cautions against the doctoring of cinema in such spaces, dangers of standardisation and homogenisation of voices and techniques. How did you learn to navigate that? At what stage was the script in when you embarked on the lab route?

Since I’m not a studied filmmaker, I thought the labs could give me access to industry professionals and mentorship. I did have my screenplay ready before I began going to the labs. The first was the NFDC one, my mentor being Umesh Kulkarni. He encouraged me, insisting my screenplay was already well-honed. At most, few minor details might need reworking. He told me to just work towards making the film and not get stuck in doing the lab rounds.

What Carlos says is true. It did happen in my case. Few other mentors were trying to put their thoughts of what should happen, but I knew what I wanted to make. So I didn’t let that happen. It might bring doubts in you since these are seniors and industry experts. There were few interesting additions which did help me hone the script in nice ways. But there were some important things I fought for. There was one suggestion to explore death, but I insisted my film isn’t about death. Though the film opens with death, I wanted to change the journey towards a tender one. Rather, in this grieving period associated with sadness and loneliness, the character finds love. There were also suggestions around the climax.

Many mentors told me the boys shouldn’t come together but separate. I was puzzled. I didn’t want to make such a film. It’d be pointless. Another mentor told me the boy should stand up to the village. I wasn’t interested in doing any of that. I know so many people in real life who haven’t stood in front of the society, yet found their ways of navigating happiness and are leading their lives comfortably. I wanted to tell such stories. That’s how people could relate to it a lot. I didn’t want to make a film where everything is sad. Many said the film should end in the village. I told them Anand, who lost his father, has spent most of his time in the house in the city. He would feel his father’s absence only in the city. That’s when he cries. Him being in the arms of Balya as they sleep together—I wanted all of this and that’s why the film had to end in the city. So, when you go to the labs, you should know what to filter out. You know best since you are making the film.

Let’s talk about storyboarding, which you do extensively. Jane Campion says the more you do it, the more you have psychic control over it. Many other directors say they don’t look at the storyboards again right before filming. Do you follow it like a Bible through the filming?

Yes, my DP (Vikas Urs) and I followed it pretty much. I’d say he was more so invested in doing this. Occasionally, during filming, if locations changed, some shots had to be replaced. I think carefully about framing in pre-production when there’s a lot of time. I don’t feel comfortable in going on shoot and then figuring out what the scenes would look like. Since I am an interior designer, I have a gut feeling about what works when I draw. If it doesn’t, I keep redrawing until I arrive at a frame that feels interesting. For me, storyboarding is a way of rewriting the film, by which I can simplify the scenes. Film is a visual medium. At the end of the day, we are making images. If I can draw it all out and it helps the team, why shouldn’t I embrace it? This is how I eliminate over-shooting.

Every morning during shoot on the way to the location, Vikas would diligently go through the storyboard, each shot planned on that particular day. Two months, before filming, we went extensively through the storyboards. But yeah, everyone has their own process. I don’t buy into any precise science of storytelling. Nobody should be forced into accepting only a particular kind of screenplay development.

Tell me about Neeraj Churi, the primary producer, who had faith in your voice right from your short through the five-year-long journey of this film from Arms of a Man to Sabar Bonda…

We met in 2017 at a film festival. He had seen few of my short films. I remember when U for Usha (2019) was playing at a film festival in Cardiff, we were at a bar in London and he asked me what I’d like to do in the next five years. I told him that I’d like to make my feature. He was surprised that I hadn’t said anything about becoming successful or famous. But once you make a good film, those things will follow. This year in June, when we had our UK premiere at SXSW, he took me to the same bar and I reminded him of our conversation (smiles). He keeps saying my conviction drives him. He even had to mortgage his house, else there would have been no film. I wish we have enough people to enable stories of emerging filmmakers. I met Nagraj Manjule yesterday and he was saying that nobody understood what he wanted to make while pitching Sairat.

In these five years of making, what did you say to yourself when the going got tough, the moments of extreme doubt?

I don’t ever think the film will not get made. I am mostly uncertain regarding how it will work out. I never leave my scripts unfinished thinking what if they don’t see the light of day. Whenever I have an idea, I toy with it for as long as I can.

Of course, there are doubts and rejections. Sundance had rejected the screenplay in 2021. These are big heartbreaks. But at least, unlike my previous feature scripts, I managed to get people on board for this one.

There’s this dry aridity that seeps through the frames. In terms of actual production, once filming began, was there anything that especially felt tricky in sticking this constant sensation through erratic weather?

Firstly, the village is dry in nature so I knew I’d get the brown shade throughout. But the problem was the rain that started once we began filming. It didn’t even rain in monsoon that year and we were shooting in winter. Many don’t realise that the sequence when Anand goes with Balya and the goats and they sit under the tree was shot with a cloudy sky. It was the first day of shoot. We managed somehow, but most days we had to shoot only when the light was bright. You cannot get these things in post-production. That’s why I feel like I don’t want to shoot my next film outdoors, with global warming getting worse and worse.

I wanted cactus pears but there was no fruit in the village. The tree that you see in the film had no fruits. That was VFX. I was wondering how I’ll show Anand eating the fruit. The villagers said it didn’t rain since the beginning of the year which was why there was no fruit. Plus the villagers had slashed on the cactus, saying it’s useless and sucks all water, and mango trees. We went on a search of sourcing the fruit and found a contact of a person who sells the fruit to pharma companies, who was from Gujarat. That’s how we got the real fruit which Anand eats.

But one good thing that happened was the lake that you see in the film got filled in all the rain during shoot (chuckles). So, the rain too helped in a way.

What kind of actors’ director are you? How hands on and minute do you like to be in crafting performances? Do you prefer actors being just empty vessels ready to receive anything you say? Do you like improvisations? Did the cast also give a lot of suggestions?

You should ask that to the actors. But yes, I do like to be in control. We used to gather on Zoom every evening. I’d ask the actors to read the dialogues first and then share how I’m imagining the scenes. It was for nailing the tone. During the shoot, I’d shape the physical performances. I told them clearly what I wanted. Only a director can see the film in his or her mind and has to accordingly communicate. I’m happy I got actors who could respond to my direction and arrive at the desired tone. They too gave inputs which were incorporated if they fitted in. Like that scene with Anand and his mother, him lying on the verandah—it wasn’t like that in the screenplay. It came from Bhushaan. You have to be open and absorb what works in the moment.

In the film, there’s this great weight that builds from Anand holding himself back. Balya strikes as this initiator in whose company Anand slowly starts to blossom and open up. Were you always keen on this kind of juxtaposition?

Much of this has to do with the particular situation Anand is in—the grief and the beleaguering by his relatives for him to marry. Anand is out to his parents, Balya isn’t. Balya being a farmer keeps getting rejected by women. The contrast lies there.

The film builds its emotional pull through these extraordinary still long takes. Does the editor’s job become tougher when you have these long takes? How involved do you like to be in the early stages of edit?

I’m deeply involved in every part of the process. I sat with my sound designer for a year. The first assembly of the shots was done by Anadi (the editor). He prepared a rough cut. Then, once we shifted through the various cuts, I sat with him throughout. It was difficult because everything has been spoken in a long take and there’s no coverage. Where do you choose to begin and end? If certain beginning points need to be deleted, you have to carefully think it through. Anadi shuffled various scenes around. That’s the significance of an editor’s perspective.

When Apichatpong Weerasethakul was asked about queer expression in his work, he said to him queer means anything can happen, that it’s about openness to possibilities. But then there’s someone like Celine Sciamma who insists on a particular lesbian gaze, that there’s strength in the reclamation. She says calling her film lesbian is political, not limiting. How do you reflect on queerness, not necessarily in terms of identity, but as philosophy and shaping artistic practice?

Honestly, I really don’t think about any of these things (laughs). Once you do, it might limit your creativity. At its heart, you could say Sabar Bonda is a queer film. However, I didn’t approach it as one. You’ll see many queer films surround themselves a lot with identity and acceptance. I don’t see my sexuality as my identity, rather a part of my personal life. I thought the premise could be interesting—a love story within a ten-day grieving period. I could incorporate the customs I experienced and the rural side of sexuality. I’m more interested in images and sounds when I start thinking of an idea. I want the audience to look at this relationship between the men in the film just like any other love story. Many heterosexual men came up and told me not to label this a queer film. They were touched by the purity of the love and found it heartening.

Amidst the film being now backed by industry stalwarts as Executive Producers, what are your hopes from the Indian theatrical release?

My only wish is that people should experience it in the cinema. We really took great efforts to sculpt certain images and sounds. I spoke to Nagraj Manjule today (one of the EPs); he saw the film last week itself and was ready to come on board. I hope audiences like it as well.

Have you shown the film to the villagers?

We’ll be inviting them to the cast and crew screening.

And just how cool is it to have Strand Releasing be your North American distributor? They’ve handled so many films of Apichatpong, Claire Denis, Celine Sciamma…

Watching world cinema, I grew acquainted with so many such production houses, distributors. Now seeing the logo of Strand Releasing come up in my film is one of the most exciting things. I always have high expectations. I knew I wanted to take my film to one of the top five film festivals. I wanted a theatrical release no matter what people say. I want to set high goals for myself. When I went to Strand’s office in LA, I couldn’t stop taking pictures of all the amazing films they have distributed. Marcus, the owner of Strand Releasing, is such an amazing, friendly person. The North American release is happening in November.

I know you have an alarm set to write something every day. Is there anything you can share that you may have zeroed in on for your next?

I do have ideas, but it’s too early. The global warming thing and having to manage a large cast in Sabar Bonda make me want to do something where I can control everything. In my next film, I want to put restrictions on myself and see how I could then tell a story. Maybe limitations, like in the case of Iranian films, could help me try out different things. Once the release of this film is all done with, I’ll sit down to work on the next. I feel I’m still caught in the emotional and mental world of this film. I just need a break where I’m not doing anything and that boredom might push me to sit down and write.