Summary of this article

The 56th International Film Festival of India ran at Goa from November 20 to 28 and screened more than 240 films from 81 countries.

Over 50 of the films are directed by women, along with a prominent presence of queer and gender-fluid stories across the programme.

This year’s selection felt both wide and opportunistic in the best way—it landed almost every big prize winner of the season.

The 56th International Film Festival of India (IFFI) in Goa managed to be casually huge and casually chilled at the same time. Where else can you sit through a three-hour Taiwanese classic Yi Yi (2000) in a glorious 4K restoration, or watch a new Lav Diaz epic Magellan (credit to the festival for standing by him through both his triumphs and misfires), and end up on the beach arguing—with a level of conviction better saved for real causes—about the only correct way to mix cashew feni so it becomes drinkable? Officially, the festival ran from November 20 to 28 and screened more than 240 films from 81 countries, with over 50 directed by women, along with a prominent presence of queer and gender-fluid stories across the programme.

This year’s selection felt both wide and opportunistic in the best way—it landed almost every big prize winner of the season. Palme d’Or, Golden Bear, Golden Lion, Golden Leopard and Tiger were all on the bill, turning Goa briefly into a golden zoo. With MAMI on hiatus in 2025, Goa faced little domestic competition for premieres, which helped secure a lineup heavy on festival favourites. The only conspicuous absentees were Bi Gan’s Resurrection and The Voice of Hind Rajab, both of which went to Kolkata instead. Given the political temperature around the latter, its non-appearance in Goa can hardly be called surprising. What felt significantly weaker, however, were the documentary and experimental programmes. Whether that reflects a programming choice or simply a quieter year for such work remains an open question.

Traditionally, the weak spot of IFFI has been its Indian selection, and this year did little to change that. In the festival’s understandable desire to avoid controversy and keep the waters calm, several of the season’s major Indian titles were missing. In their place came the familiar, safer choices, including films like Ground Zero or The Bengal Files, both of which had already completed their theatrical runs. Still, a few fresher notes appeared, most notably the gender-bender love story Lala and Poppy, which suggested that at least part of the selection committee was willing to look beyond the usual comfort zone.

There were also noticeable shifts this year that went beyond programming. The festival’s demographics skewed younger, and the culture of attendance changed with them. And since online booking has become as cutthroat as it is in Mumbai or Kerala, every slot suddenly carried weight. Walkouts were far fewer, though this did not entirely eliminate the customary snoring soundtrack that sometimes drifts through Goan screenings. Another welcome development was the softening of the old rule against rush lines—a relic of the Covid era that has somehow outlived every other restriction and common sense combined. The festival quietly relaxed its ban (leaving the practice of walk-ins in a grey zone), sparing everyone the absurdity of being turned away from a hall that was half-empty and fully guarded by protocol.

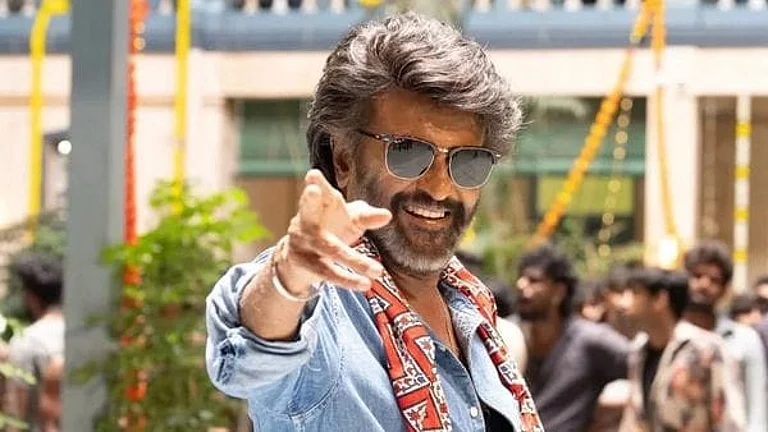

Against the backdrop of a felicitation for Rajinikanth, the awards at the closing ceremony felt—as they often do at festivals—like a modest exercise in unpredictability. The Golden Peacock for best film went to the Vietnamese entry Skin of Youth by Ash Mayfair, a 1990s Saigon-set romance that the festival catalogue describes as a turbulent tale of two young lovers struggling for identity and freedom. The film, however, often pushes its material towards sustained, brutal set pieces and at times verges on gratuitousness, testing the line between urgent moral drama and exploitative imagery.

The Silver Peacock for best director was awarded to Santosh Davakhar for Gondhal, a Marathi thriller that stages a single night of ritual and wedding ceremony as the setting for jealousy, conspiracy and a deadly mystery.

Other noteworthy winners included A Poet, directed by Simón Mesa Soto, which earned Ubeimar Rios the Best Actor prize, and My Father’s Shadow, directed by Akinola Davies Jr., which took the Special Jury Prize. In the Colombian film, a nonprofessional philosophy professor-turned-actor reportedly reshaped the project during casting, prompting Soto to admit the film changed completely from his original plan. The absurdist tragicomedy, Soto says, allowed him to explore “the worst version of himself” and, paradoxically, to rediscover “the ultimate dreamer,” reviving his declining enthusiasm for filmmaking after the pandemic.

The Nigerian film follows two boys and their complicated relationship with their father as the country’s hope for democracy collapses during the 1993 elections. Visually, it is gorgeous, bathed in warm, dust-lit colours that make every frame feel tactile and lived-in. Thematically, it is strong, weaving national politics into the small, stubborn rituals of childhood and family duty. At moments, the film echoes the quiet intimacy of Moonlight (2016) and the humane urgency of Bicycle Thieves (1948) and, as Davies Jr. puts it, “an elegy for an unfulfilled potential for the generation of my parents that once believed Nigeria would become the Giant of Africa.”

Both films find a surprising unity in their choice of 16mm. In A Poet, shooting on 16mm forced exhaustive rehearsals because the production could not afford more than two takes per shot and that constraint shaped the performances. More broadly, a clear visual thread ran through the programme: a turn to analogue. Filmmakers favoured Super 8, 16mm and 35mm and embraced quasi-archival, damaged-film effects in a nostalgic urge to recover the texture, authenticity and fragile imperfections that clinically cold, perfectly distilled digital wipes out.

Similarly rich in analogue texture and visually expressive were two Peruvian films—The Memory of Butterflies by Tatiana Sadowski and Punku by J. D. Fernández Molero. Sadowski’s film constructs a deliberately unstable archive around two Indigenous men photographed in London in 1911 after being brought from the Amazon by an Irish activist, who hoped their testimony would expose the genocidal rubber trade. Rather than treating the photograph as proof, the film makes it a collapsing portal: archival certainty gives way to speculative hauntology. Sadowski refuses to fill the gaps with tidy narratives, instead intercutting genuine colonial footage with her own hand-processed Super 8—imagery degraded, solarised, and shot among present-day Amazonian communities—hence, collapsing temporal boundaries and foregrounding absence.

Punku, meaning “gateway” or “portal” in Quechua, screened in the ‘Cinema of the World’ strand and follows the same tactile logic. Fernández Molero stitches 16mm, Super 8 and digital into a deliberately frayed tapestry, producing a jungle fever dream where Lynch wanders into Apichatpong territory. Inspired by childhood episodes of sleep paralysis, the film inhabits that third state between waking and sleep, where vision slips and time folds. The result is less a story than an immersive field of consciousness, each texture evoking a different layer of memory and perception rather than offering neat narrative closure.

Moving from the jungle’s feverish portals to a different kind of immersion, the festival’s most overwhelming experiences came from two fierce female voices, each wielding a distinctly sensory visual language. Both films are powerful artistic statements on the histories of violence and the complex, often jagged, paths to redemption or the lack thereof. One is The Sound of Falling by Mascha Schilinski. It is a multilayered cinematic puzzle that feels destined to be one of the defining films of the year. Unfolding across a century on a single German farm, it weaves together the lives of four generations of women into a single, fluid "time-image", where the past does not haunt the present, so much as rot alongside it. Stunningly shot in a coarse, grainy 4:3 frame with 35mm film, it clearly draws inspiration from 19th-century post-mortem imagery and iconography of the Pre-Raphaelites, and the ghostly self-portraits of Francesca Woodman as well as the clinical dread of Michael Haneke’s The White Ribbon and the psychological interiority of Ingmar Bergman’s Cries and Whispers. Bleak and demanding—a 149-minute descent into inherited trauma and suicidal ideation—it is nonetheless a genuine cinematic feast, rewarding for its patient viewers.

Kristen Stewart’s debut Chronology of Water may, at first glance, seem like the lightweight in comparison. But the film feels deliberately unvarnished, even unruly, as if its own form were struggling to contain the traumatic core of Lidia Yuknavitch’s anti-memoir. Stewart leans into the rawness of the material: a coming-of-age shaped by an abusive father, addiction, self-destruction and the messy work of survival. What emerges is a hot, wet tangle of memories, emotions, bodily fluids and damaged film stock (again, 16mm)—a sensory overflow that mirrors Yuknavitch’s refusal to polish her pain into narrative clarity. Rather than controlling the material, Stewart lets it spill, smear and burn through the frame, producing a film that is far from perfect, but breathtakingly alive.

It is tempting to read the analogue wave at this year’s IFFI as some grand artistic pivot, but that would be wishful thinking—nobody should mistake it for a grand manifesto of resistance. The overall drift of filmmaking towards the glossy inevitability of digital remains as unstoppable as the gentrification of Panjim’s old quarters, where Fontainhas now serves mainly as a backdrop for tourists photographing themselves against aggressively restored colonial facades. This edition also quietly hosted India’s first AI-focused, modest, sparsely discussed sidebar that nevertheless pointed to a coming shift that will not ask for permission. For the moment, though, IFFI itself still resembles a severely scratched Super 8 reel: bloated in places, uneven and a structurally flawed “hot, wet mess”. Yet, it’s capable of yielding the most unexpected images from the least expected corners of the world. That, finally, is its enduring value: a space of sometimes insane cultural and geographical diversity in one of the best possible settings. For all its contradictions, Goa still offers a rare space where cinema can be the question, the answer, or, on good days, mercifully neither.

Constantine is a translator and traveller, with occasional critical writing on film and visual culture.