Summary of this article

Singer and musician Lucky Ali completes 30 years in the music industry.

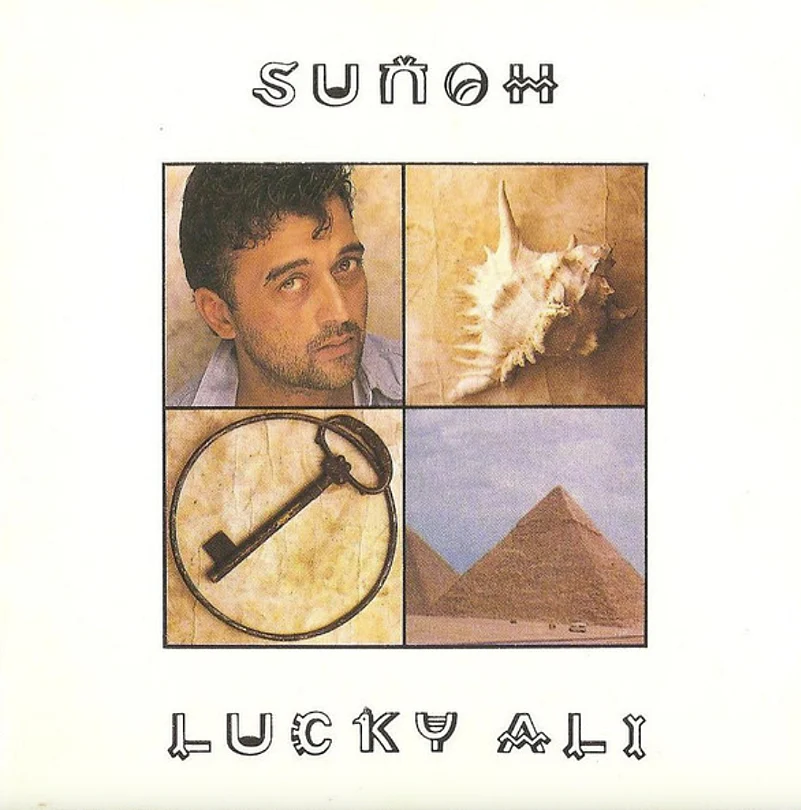

His first album Sunoh released in 1996, the same year as the launch of MTV India.

If Alisha Chinai provided the groove and Daler Mehndi the beats, Ali formed the warm, hummable parts of Indipop that anyone could break into.

As someone who had the pleasure of having an older sibling go to college while I was still in primary school, I was exposed to the joys of borrowing, sharing and recording Indipop (Indian pop) cassettes at an age that mostly involves watching cartoons. I was instead introduced to Indipop on Superhit Muqabla on Doordarshan and later MTV, while simultaneously discovering the delights of repeatability that borrowed cassettes brought with them. Amidst the assortment of Indipop artists that this shy-of-ten-year-old was being exposed to, was a hazel-eyed young man with a charmingly untutored voice.

Lucky Ali’s first album, Sunoh released in 1996, the same year as the launch of MTV India—the TV channel that became one of the driving forces behind popularising Indipop videos. Both became markers of (mostly) urban youth culture in the ‘90s and 2000s. The shifting modes of circulation and reception over the years led to the demise of MTV Music. Ali, however, remains a cultural icon for a generation that grew up in the said decades, where listening to music also comprised the painful (or joyful) act of having to procure it—borrowing or buying cassettes and CDs or making one’s own tape.

Much before he took Bollywood charts by storm with “Ek Pal Ka Jeena”, we saw him for the first time in the video of “O Sanam”—the breakout song of his debut album that continues to be a fan favourite over the decades. Shot amidst the Pyramids of Giza, the video is a bizarre narrative with fragmented storytelling, with its meaning being debated on Reddit threads to date. “O Sanam” continued to top charts for weeks, joined by the popular hits “Teri Yaadein Aati Hai”, “Dekha Hai Aise Bhi”, and “Gori Teri Aankhen” from his successive albums over the years.

Not a trained musician, Ali came from a film family. He is the son of Mehmood and nephew to Meena Kumari—two of Hindi cinema’s memorable icons. He was interested in both acting and music, trying his luck at the latter since acting did not seem to work out for him. In an interview with Rediff very early on in his career, he explained how he landed on his first song when he was 13, as he started to discover chords on his first ever guitar. There is a kind of irreverence that comes with untutored musicians, discovering and shifting between notes and chords at one’s own will, unafraid to make mistakes—an ease that is perhaps often tamed by the structures and hierarchies that come with training. It is this ease that made his singing imitable. We’ve all known that person sitting in the college or university canteen, trying out chords on their own, unafraid of consequences; some of us have been them. It is this imitability that made Ali’s independent music popular in informal gatherings. If Alisha Chinai provided the groove and Daler Mehndi the beats, Ali (along with other Indipop artists like Shaan and KK) formed the warm, hummable parts of Indipop that anyone could break into.

While Ali had done playback singing for his father’s films Ek Baap Chhe Bete (1978) and Dushman Duniya Ka (1996), his breakout came with his playback for the album of Kaho Naa Pyaar Hai (2000), especially the song “Ek Pal Ka Jeena”, which became a household hit. Since the very beginning, Ali stood out from the male playback singers dominating Bollywood with his husky and free-flowing voice. In an industry where the leading playback voices were jacketed with their heroes, Ali’s voice meandered across actors. He echoes as the haunting spectre-like voice in “Maut” from Kaante (2002) (where he starred as well) and captures the madness of young love in “Khuda Hafiz” (Yuva, 2004). His years in the industry also coincided with the increasing use of songs appearing as background to montages, as opposed to actors lip-syncing them. This not just removed the need to fit every singing voice to an actor but foregrounded the playback voice’s power to take atmospheric charge. It is in this regard that Ali’s voice shines through, whether he sings of the possibilities of love in “Hairat” (Anjaana Anjaani, 2010), or longing and finding in “Safarnama” (Tamasha, 2015).

His most elaborate cinematic outing, however, came with Sur: The Melody of Life (2002), a film he also starred in as the lead character. Based on the 1992 Telugu film Swati Kirnaam, which in turn was inspired by Amadeus (1984), the film addresses the anxieties and complexities of living the life of a famous musician. Composed by M.M Keeravani, known for his classically rooted music, the film’s music blends Hindustani classical with Western orchestral framing. Sung mostly by Ali and Sunidhi Chauhan, the album is defined by a sense of haunting surrender that beautifully captures the conflicts of two musicians who rival as well love each other. The songs of Sur ground Ali’s voice as an instrument of pain and longing, in a way that pierces as well as soothes—the echoes of which are found years later in “Safarnama”.

Despite his Bollywood success, Ali has never been fully absorbed by the industry. He has continued to release independent albums, which include, among others, “Rasta Man”, “Subah Ke Taare”, and the recently released music video “Tu Jaane Hai Kahan”—maintaining his signature acoustic style and introspective lyrics. None of these independent releases, however, have matched the dizzying popularity of his early Indipop ventures, which, over the years, have turned into nostalgic paeans to the ‘90s and 2000s, more than the love songs they were intended to be. Between these songs that were once discovered brand new on the TV and cassettes, and their forever fresh relics in the digital everywhere(s), is a voice that makes love and longing worthy of being played on loop, three decades on.

In the last few years, Ali has remained one of the few Indian celebrities to have actively spoken for the people of Palestine—at his concerts, through his videos and social media posts. If his voice has made love and longing more singable, it has also reminded us that there is no singing for love, unless there’s singing in solidarity with songs lost and childhoods maimed.